Whisper-wails, Village Festivals, and Bolero

Funeral Rites

By Arlette Quỳnh-Anh Trần, 2021To be researching death and funerals at this moment in time does not weigh lightly on the mind. Our elders have a saying »The living need light, the dead need music[1]« but in these times, families see off an ambulance carrying a loved one who has contracted Covid-19, only to be handed a jar of ashes a few days later. There isn’t time to prepare incense or a tray of fruit to send off the deceased, let alone arrange a ceremony according to respective traditions. Death – the cessation of one’s physiological body – signals the beginning of the community’s emotional expression, which manifests as the final formalities and rituals for the body that remains.

For Vietnamese people, funerals seem to be the most important of ceremonies, even compared to weddings. Aside from the band serving as the background to guests who are eating, drinking, and taking pictures, the focus of most Vietnamese weddings is its rituals – bowing to ancestors, greeting the two families, giving money and gifts – rather than its congratulatory, collective performance that is dancing, singing, and playing games. Not including the formalities hosted at home, such as the marriage proposal and engagement party, Vietnamese weddings usually take place in just a few hours – the length of a five-course banquet.

Weddings are praised and respected based on hierarchies of social class and social standing, the material value of the bride price, the bride and groom’s wedding costumes, or the venue. But these criteria cannot be applied to funerals. The deceased is a member of the family; affection and closeness must be clearly expressed by as many as possible, and leave a lasting impact in the family’s immediate and surrounding circles. The deep affection between the living and the dead is expressed in a performative and even staged manner.

It is at the funeral where the differences between Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Christianity are least clear-cut. Of course, one can still see monks praying for the peace of the soul, priests reciting from the Bible and blessing the casket with holy water, Taoist coffin seal charms, or the Dharma seals of the Three Teachings. Yet these rites are similar in that they occur over a number of days, and are held between family, relatives, friends, and neighbours. At a Vietnamese funeral, regardless of the family’s social class, one not only hears crying and chatter, but also music that serves not as mere background, but as an integral part of all funeral proceedings held on this land. Funeral music can vary from North to South, from the plains to the mid- and highlands. Although the structure of funerals does share a number of similarities, the rhythm of funeral music depends on how the people of each region conceive of death.

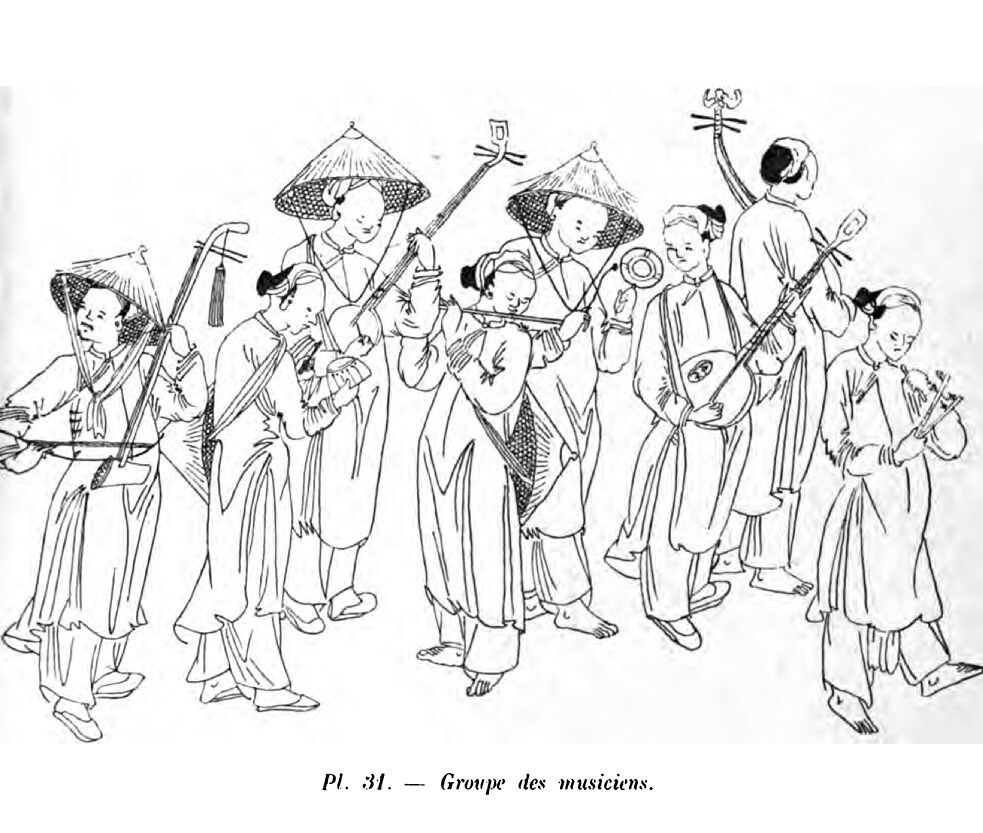

In the North, as Gustave Dumoutier notes in his book Le rituel funéraire des Annamites (The funeral ritual of the Annamites), first published in 1904, the orchestra consists of musicians playing eight different instruments, including the sinh tiền (coin clapper), đàn nguyệt (moon lute), đàn tì (pear-shaped lute), cánh (copper tympani), ống địch (bamboo flute), đàn tam (three-stringed fretless lute), and trống giằng và đàn nhị (erhu). Each instrument has a distinct timbre that comes together to form what is colloquially referred to as »phường bát âm« – an amalgam of eight sound sources corresponding to the eight fundamental elements in Taoist Bagua. Today, however, the number and type of instruments vary depending on local and group preferences, as seen in the choice between the bộc drum or ban drum.

Screenshot of an engraving of a bát âm troupe in the book, Le rituel funéraire des Annamites. Etúde d'ethnographie religieuse par Gustave Dumoutier (1904). Content is DRM-free.

Though originating from the royal courts, »phường bát âm« – less loud than the grand palace orchestras with their large horns and drums – spread to performances in village halls celebrating the village deity »thành hoàng,« and was later popularised at longevity ceremonies and funerals. »Phường bát âm« plays tunes like »Lưu Thủy,« which was initially court music. Historical records give varying accounts of when latter-day Northern funerals began to favour »phường bát âm« and the solemn dirges of its stringed instruments like đàn nguyệt, đàn nhị, đàn tì, đàn tam along with the slow, constant rhythm of leather drums, and the occasional addition of the kèn bóp, also known as kèn bầu (conical oboe with gourd-shaped wooden bell) played as solo or duet.

A band playing with the cơm drum

It is important to note here is that the kèn bầu or kèn bóp is a traditional Vietnamese wind instrument, with a body made of wood, a part of the mouthpiece made from common reed, and a bell made of gourd shell (later improved and made out of metal). It creates sounds that are subdued, and completely different from the Western-style brass instruments popular in the South and colloquially referred to as »Western horns,« which I shall discuss later in the essay. Aside from the orchestra, people often also hire a group of mourners who come to cry, so that the entire village can feel the family’s pain.

I have given an account of funerals in the Northern region, but those of the Central Highlands are a different kettle of fish altogether. One night last December, as I lay awake in the house of close friends in Gia Lai, I heard the echo of singing, of gongs. A ceremony to leave the tomb – known as »pơ thi« by the Jrai ethnic group – was taking place, but in the darkness of the highlands, we could not find our way to join the celebrations.

The reader might think it strange that a funeral can be described as celebratory. Indeed, conceptions of death in ethnic minority communities of the Central Highlands are markedly different from that of the North, sharing more similarities with those in the South. To them, death is part of the cycle of reincarnation. For the highland Jrai people, for example, upon death, one embarks on a journey of transformation, passing first through animals like crows, locusts, and grasshoppers, then into physical matter like bones and charcoal, and finally to dew drops that evaporate into the air. Nothingness thus marks the beginning of a new life.

In the practical application of that cosmological belief, the dead are buried in a makeshift tomb at the edge of the forest – an area outside of human civilisation that is not yet encroaching into the complete wilderness of the forest. The family still honours the deceased, bringing rice and collecting water to feed the soul. After a while, sometimes up to a few years, having saved up enough food and money, the family will hold »pơ thi,« the leaving the tomb ceremony to see off the dead – both their body and soul – from human life, ready for reincarnation. After the ceremony, they abandon the tomb – unlike the neighbouring Kinh people, who revisit graves every year – and let it be swallowed into the belly of the forest.

A pơ thi ceremony of Jrai people nowadays

During the pơ thi ceremony, a spacious new tomb is built, wooden statues are carved, food offerings are prepared, and »rượu cần« (a fermented rice wine) is brought out as a treat for guests. A set of gongs is always present, indispensable to the celebrations. After the offerings have been made and the moon has risen to the top of the tomb house’s »kút« pillar, or in other words at midnight, the ceremony begins. Under the flickering firelight, young men in the village play the gongs, dance to the tapping rhythm, and sing accompaniments to joyful songs so that the dead can readily leave this life and move onto the next one. Villagers hear the gongs and recognise them as a call to join the ceremony. Each village only has a few precious sets of gongs made from bronze, sometimes alloyed with gold, silver, or Corinthian bronze. Each set has from six to over 10 pieces that can be used separately, though on special occasions like »pơ thi« the entire set is used. Their dimensions vary between 20cm to 90cm in diameter. Depending on the ethnic group, there are distinct ways to create a scale with three, five, or six major notes with many different minor ones. When the complete set is played together, the metal vibrations resonate at different timbres, creating a dynamic piece of music full of depth and richness. Music is played through the night until the next morning, when the family delivers wine and meat to the tomb house, and cooks a feast. The family mourns for the last time, and players will once again sound the gongs to stir up a joyous atmosphere. The feast ends, the family says goodbye to the soul of the deceased and dances along to the rhythm of the gongs, heading back to the village where they shower and change into fresh clothes, officially ending the mourning period and forgetting about the lost family member in order to start a new life.

At this point, it is evident that ethnic minority groups in the Central Highlands have a decisive attitude in bidding farewell to the dead, and view death itself with levity. The Southern people, in particular those from Saigon and the Mekong Delta, are similar in this regard. With no hired mourners in sight, funerals in the South occur in the spirit of helping the deceased depart in peace, without any entanglements to those left in the mortal world. Nevertheless, burial methods in the South are different from that of the Central Highlands and the North.

Heading down to the Mekong Delta, passersby can often see graves in the gardens of people’s homes. It is unclear where the custom to »live among graves« originated. What it does show is the lack of fear of death, which is seen simply by the local people as a part of the cycle of life: once you stop living inside the family house, you will be buried in the ground of the family garden. In the past, in the hopes of extending longevity for the elderly, well-to-do families would even prepare coffins for the grandparents and leave them in the annex or near the bed. Common families would engage in »kim tỉnh« – digging graves to be ready for later burial. Such an optimistic way of thinking about death makes Southern funerals light-hearted and bustling.

As mentioned above, the Vietnamese funeral is a staged event with many acts and rituals. Funerals are rueful tragedies in the North and are filled with tribal rhythms in the Central Highlands, yet it is difficult to determine the nature of funerals in the South, where they teem with displays of tragedy that endlessly alternate with elements of popular entertainment.

To better understand the variety show-like quality of Southern funerals, I would like to veer off on a tangential discussion of different approaches to services from North to South in »Đạo Mẫu« – the Vietnamese worship of mother goddesses – which may act as a cross-reference for the funeral customs of the South. Traditionally in Đạo Mẫu in the North, mediumship is the core ritual and practiced by »đồng cô« and »đồng cậu.« The terms »đồng cô« and »đồng cậu« refer to people with the ability to approach the gods through the ritual practice »lên đồng« – mediumship rituals where spirits and deities enter a person’s body – and grant wishes to those who have come to pray. The process comprises multiple elements like costumes, dance gestures, music, and »chầu văn« songs. Here, the medium is embodying the spirit of the »divine.« The Southern rituals are different; instead of mediumship, the ritual leader worships by dancing and singing for the deities in rituals named »múa hát bóng rỗi.« According to Professor Ngô Đức Thịnh in Lên Đồng – Hành trình của thần linh và thân phận (Lên Đồng – The journey of spirits and destiny), besides the costumes, these dancers also use special props like a golden tray, in a ritual which »is the product of interactions between Chăm, Khmer, and Vietnamese culture, [...] has the quality of being magical and unusual, close to that of a variety ›circus,‹ [...and] that, for the common folk, is entertainment for the goddesses.« We can see from the long-standing »Đạo Mẫu« ritual that the hybrid nature of its performance has become the typical model for other performance practices as people migrate to the South. The penchant for entertainment, with its sense of ease, lack of hierarchical positioning, and lack of want to attain the heights of the divine, conversely makes it all the more powerful, and for me marks a notable characteristic for rituals in the region. Such performativity shifts between different forms of ceremony, from »Đạo Mẫu« to funeral rites.

The variety show quality of Southern funerals is demonstrated through their lively musical sets, with additional performances from backup dancers – performers who crossdress or are transgender, and boldly display the body’s extraordinary abilities via acts such as torch swallowing, plate spinning, acrobatics, etc. Funeral music is performed by an orchestra using Western instruments that are colloquially named »đội ›kèn Tây‹« (lit. band of »Western horns«) – the resultant hybrid between traditional rituals and Western music. In Rock Hà Nội, Bolero Sài Gòn, the composer and music historian Jason Gibbs posits that the influence of Western music in Vietnam came from 18th and 19th century Roman Catholic missionaries, who taught their congregation the basics of church music. Later, when »cải lương« – a form of folk theatre that grew out of »đờn ca tài tử« (lit. music of amateurs) in the Mekong Delta in the early 20th century – married the traditional pentatonic scale and Western instruments, the then-colonial power was also making efforts to popularise Western culture, notably musical theatre. Marches with lively, uplifting melodies such as »La Marseillaise,« incidentally the French national anthem, and »La Madelon« were loved by both the populace and younger generations of Vietnamese musicians. Brass instruments were thus introduced to the repertoire of Vietnamese music. The brass section of funeral orchestras often consists of ten musicians wearing formal attire, usually a suit or a dress shirt and tie, playing the drums, trumpet, saxophone, trombone etc., with strings rarely if at all included. For sizeable Southern funerals, the brass band may include up to 30 players, with the trumpet as the focal point of the musical arrangement and the remaining instruments as auxiliaries. This is a world apart from Northern »phường bát âm,« where wind instruments consist of the kèn bầu playing solo on a background of percussion and strings with the volume just so.

A performance by ‘Đội Kèn Tây' at a funeral in Kien Giang, a southern province of Mekong Delta

»Đội ›kèn Tây‹« often play tunes on request, meaning the family’s and visitors’ best-loved songs as well as the favourites of the deceased. Due to its »hospitable« nature, Southern funeral music reflects the taste of the general populace, especially the genres of lyrical love songs influenced by folk music that people often call »nhạc sến« (lit. cheesy music), Cuban bolero, or »nhạc vàng« (pre-war music; lit. golden music). The names of these genres are often used interchangeably even though they do have their differences. Nevertheless, they all rose to popularity among the youths of Saigon in the 1950s, when Latin music and dances such as rumba and bolero were introduced to the mainstream. Singers and musicians made Vietnamese versions of the lyrics on top of the vibrant rhythms of rumba and bolero, writing songs mainly about the love between couples, or family. This genre of music persisted because it suited the tastes of Southern listeners, though it was forced underground after 1975 due to a State ban. People then continued to casually listen to »nhạc vàng« and bolero within the confines of the family, or via musical concert series by the Vietnamese diasporic community such as Paris by Night, but for a few decades, during the official ban, these musics could only be played loudly and publicly for the »kèn Tây« ritual at funerals. According to this news clip, the Department of Culture and Information even issued a ban in 2000, prohibiting funeral bands from playing »nhạc vàng!« – though as with other music censorship laws, this law is not officially written into policy and enforcement is not uniform across the provinces.

»Đội Kèn Tây« playing revolutionary music based on the host’s request: the »Hát Mãi Khúc Quân Hành« (Singing Long Live Army March) and »Đoàn Vệ Quốc Quân« (Union of the National Defense Army). While popular funeral songs are about family and compassion, in this funeral, perhaps the deceased had worked in the army, as the songs requested have a heroic atmosphere and fast-paced rhythm.

Many similarities to the entertainment at funerals in Southern Vietnam with »Đội Kèn Tây« can be found in several different regions of the world. For example, the African-American community in New Orleans has a funeral jazz ceremony, from which artist collective The Propeller Group was inspired to create the work »The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music« (2014) combining Vietnamese and Black American ritual music. In Taiwan, a women’s brass group named Xiu Juan Female Music Band has created an international fanbase in the recent decade. The group features young musicians wearing short pleated skirt uniforms that give performances similar to the entertaining parades at Vietnamese funerals.

Xiu Juan band performing brass music and a marching dance at a funeral in Taiwan

Regional differences exist in any country, and in any ritual or daily custom. When it comes to entertainment, Southern Vietnamese people only watch comedy shows from Saigon or Mekong Delta troupes and feel distant from Northern-style comedy because of its seriousness. Likewise Northern audiences do not like the comedy theater in the South as they consider it too superficial. But there is a Vietnamese proverb: »Respect in death is the final respect«[2]: all manner of pain and earthly emotions will be shaken off in death. The funeral, therefore, is the last chapter of one’s fate. We do not choose how we are born, and when we die, everything comes down to the family's choice of that final song with which to send us off. Families inherit customs from their places of origin, and nurture these within their own family story. Funeral music, then, is probably most closely linked to a specific place as well as one’s memories.

Craig Duncan, Saigon, East of New Orleans: The Surprising Global Roots of Vietnam's Funeral Marching Bands, on Saigoneer

Đức Thịnh Ngô. Lên đồng, hành trình của thần linh và thân phận (Len dong, journeys of spirits, bodies, and destinies), Nhà xuất bản Trẻ, 2008.

Jason Gibbs, Rock Hà Nội và Rumba Cửu Long, übersetzt von Nguyễn Trương Quý, NXB Tri thức, 2008.

Jason Gibbs, Nhìn lại quá trình kiểm duyệt nhạc Việt qua năm tháng (auf Vietnamesisch). An overview of music censorship in Vietnam through the time, im BBC.

A glossary of Vietnamese folk songs and traditional instruments (in Vietnamese)

[1] »Sống dầu đèn, chết kèn trống,« translated following the title of an artwork created by The Propeller Group in 2014.

[2] »Nghĩa tử là nghĩa tận«

Weddings are praised and respected based on hierarchies of social class and social standing, the material value of the bride price, the bride and groom’s wedding costumes, or the venue. But these criteria cannot be applied to funerals. The deceased is a member of the family; affection and closeness must be clearly expressed by as many as possible, and leave a lasting impact in the family’s immediate and surrounding circles. The deep affection between the living and the dead is expressed in a performative and even staged manner.

It is at the funeral where the differences between Buddhism, Confucianism, Taoism, and Christianity are least clear-cut. Of course, one can still see monks praying for the peace of the soul, priests reciting from the Bible and blessing the casket with holy water, Taoist coffin seal charms, or the Dharma seals of the Three Teachings. Yet these rites are similar in that they occur over a number of days, and are held between family, relatives, friends, and neighbours. At a Vietnamese funeral, regardless of the family’s social class, one not only hears crying and chatter, but also music that serves not as mere background, but as an integral part of all funeral proceedings held on this land. Funeral music can vary from North to South, from the plains to the mid- and highlands. Although the structure of funerals does share a number of similarities, the rhythm of funeral music depends on how the people of each region conceive of death.

In the North, as Gustave Dumoutier notes in his book Le rituel funéraire des Annamites (The funeral ritual of the Annamites), first published in 1904, the orchestra consists of musicians playing eight different instruments, including the sinh tiền (coin clapper), đàn nguyệt (moon lute), đàn tì (pear-shaped lute), cánh (copper tympani), ống địch (bamboo flute), đàn tam (three-stringed fretless lute), and trống giằng và đàn nhị (erhu). Each instrument has a distinct timbre that comes together to form what is colloquially referred to as »phường bát âm« – an amalgam of eight sound sources corresponding to the eight fundamental elements in Taoist Bagua. Today, however, the number and type of instruments vary depending on local and group preferences, as seen in the choice between the bộc drum or ban drum.

Screenshot of an engraving of a bát âm troupe in the book, Le rituel funéraire des Annamites. Etúde d'ethnographie religieuse par Gustave Dumoutier (1904). Content is DRM-free.

Though originating from the royal courts, »phường bát âm« – less loud than the grand palace orchestras with their large horns and drums – spread to performances in village halls celebrating the village deity »thành hoàng,« and was later popularised at longevity ceremonies and funerals. »Phường bát âm« plays tunes like »Lưu Thủy,« which was initially court music. Historical records give varying accounts of when latter-day Northern funerals began to favour »phường bát âm« and the solemn dirges of its stringed instruments like đàn nguyệt, đàn nhị, đàn tì, đàn tam along with the slow, constant rhythm of leather drums, and the occasional addition of the kèn bóp, also known as kèn bầu (conical oboe with gourd-shaped wooden bell) played as solo or duet.

A band playing with the cơm drum

It is important to note here is that the kèn bầu or kèn bóp is a traditional Vietnamese wind instrument, with a body made of wood, a part of the mouthpiece made from common reed, and a bell made of gourd shell (later improved and made out of metal). It creates sounds that are subdued, and completely different from the Western-style brass instruments popular in the South and colloquially referred to as »Western horns,« which I shall discuss later in the essay. Aside from the orchestra, people often also hire a group of mourners who come to cry, so that the entire village can feel the family’s pain.

I have given an account of funerals in the Northern region, but those of the Central Highlands are a different kettle of fish altogether. One night last December, as I lay awake in the house of close friends in Gia Lai, I heard the echo of singing, of gongs. A ceremony to leave the tomb – known as »pơ thi« by the Jrai ethnic group – was taking place, but in the darkness of the highlands, we could not find our way to join the celebrations.

The reader might think it strange that a funeral can be described as celebratory. Indeed, conceptions of death in ethnic minority communities of the Central Highlands are markedly different from that of the North, sharing more similarities with those in the South. To them, death is part of the cycle of reincarnation. For the highland Jrai people, for example, upon death, one embarks on a journey of transformation, passing first through animals like crows, locusts, and grasshoppers, then into physical matter like bones and charcoal, and finally to dew drops that evaporate into the air. Nothingness thus marks the beginning of a new life.

In the practical application of that cosmological belief, the dead are buried in a makeshift tomb at the edge of the forest – an area outside of human civilisation that is not yet encroaching into the complete wilderness of the forest. The family still honours the deceased, bringing rice and collecting water to feed the soul. After a while, sometimes up to a few years, having saved up enough food and money, the family will hold »pơ thi,« the leaving the tomb ceremony to see off the dead – both their body and soul – from human life, ready for reincarnation. After the ceremony, they abandon the tomb – unlike the neighbouring Kinh people, who revisit graves every year – and let it be swallowed into the belly of the forest.

A pơ thi ceremony of Jrai people nowadays

During the pơ thi ceremony, a spacious new tomb is built, wooden statues are carved, food offerings are prepared, and »rượu cần« (a fermented rice wine) is brought out as a treat for guests. A set of gongs is always present, indispensable to the celebrations. After the offerings have been made and the moon has risen to the top of the tomb house’s »kút« pillar, or in other words at midnight, the ceremony begins. Under the flickering firelight, young men in the village play the gongs, dance to the tapping rhythm, and sing accompaniments to joyful songs so that the dead can readily leave this life and move onto the next one. Villagers hear the gongs and recognise them as a call to join the ceremony. Each village only has a few precious sets of gongs made from bronze, sometimes alloyed with gold, silver, or Corinthian bronze. Each set has from six to over 10 pieces that can be used separately, though on special occasions like »pơ thi« the entire set is used. Their dimensions vary between 20cm to 90cm in diameter. Depending on the ethnic group, there are distinct ways to create a scale with three, five, or six major notes with many different minor ones. When the complete set is played together, the metal vibrations resonate at different timbres, creating a dynamic piece of music full of depth and richness. Music is played through the night until the next morning, when the family delivers wine and meat to the tomb house, and cooks a feast. The family mourns for the last time, and players will once again sound the gongs to stir up a joyous atmosphere. The feast ends, the family says goodbye to the soul of the deceased and dances along to the rhythm of the gongs, heading back to the village where they shower and change into fresh clothes, officially ending the mourning period and forgetting about the lost family member in order to start a new life.

At this point, it is evident that ethnic minority groups in the Central Highlands have a decisive attitude in bidding farewell to the dead, and view death itself with levity. The Southern people, in particular those from Saigon and the Mekong Delta, are similar in this regard. With no hired mourners in sight, funerals in the South occur in the spirit of helping the deceased depart in peace, without any entanglements to those left in the mortal world. Nevertheless, burial methods in the South are different from that of the Central Highlands and the North.

Heading down to the Mekong Delta, passersby can often see graves in the gardens of people’s homes. It is unclear where the custom to »live among graves« originated. What it does show is the lack of fear of death, which is seen simply by the local people as a part of the cycle of life: once you stop living inside the family house, you will be buried in the ground of the family garden. In the past, in the hopes of extending longevity for the elderly, well-to-do families would even prepare coffins for the grandparents and leave them in the annex or near the bed. Common families would engage in »kim tỉnh« – digging graves to be ready for later burial. Such an optimistic way of thinking about death makes Southern funerals light-hearted and bustling.

As mentioned above, the Vietnamese funeral is a staged event with many acts and rituals. Funerals are rueful tragedies in the North and are filled with tribal rhythms in the Central Highlands, yet it is difficult to determine the nature of funerals in the South, where they teem with displays of tragedy that endlessly alternate with elements of popular entertainment.

To better understand the variety show-like quality of Southern funerals, I would like to veer off on a tangential discussion of different approaches to services from North to South in »Đạo Mẫu« – the Vietnamese worship of mother goddesses – which may act as a cross-reference for the funeral customs of the South. Traditionally in Đạo Mẫu in the North, mediumship is the core ritual and practiced by »đồng cô« and »đồng cậu.« The terms »đồng cô« and »đồng cậu« refer to people with the ability to approach the gods through the ritual practice »lên đồng« – mediumship rituals where spirits and deities enter a person’s body – and grant wishes to those who have come to pray. The process comprises multiple elements like costumes, dance gestures, music, and »chầu văn« songs. Here, the medium is embodying the spirit of the »divine.« The Southern rituals are different; instead of mediumship, the ritual leader worships by dancing and singing for the deities in rituals named »múa hát bóng rỗi.« According to Professor Ngô Đức Thịnh in Lên Đồng – Hành trình của thần linh và thân phận (Lên Đồng – The journey of spirits and destiny), besides the costumes, these dancers also use special props like a golden tray, in a ritual which »is the product of interactions between Chăm, Khmer, and Vietnamese culture, [...] has the quality of being magical and unusual, close to that of a variety ›circus,‹ [...and] that, for the common folk, is entertainment for the goddesses.« We can see from the long-standing »Đạo Mẫu« ritual that the hybrid nature of its performance has become the typical model for other performance practices as people migrate to the South. The penchant for entertainment, with its sense of ease, lack of hierarchical positioning, and lack of want to attain the heights of the divine, conversely makes it all the more powerful, and for me marks a notable characteristic for rituals in the region. Such performativity shifts between different forms of ceremony, from »Đạo Mẫu« to funeral rites.

The variety show quality of Southern funerals is demonstrated through their lively musical sets, with additional performances from backup dancers – performers who crossdress or are transgender, and boldly display the body’s extraordinary abilities via acts such as torch swallowing, plate spinning, acrobatics, etc. Funeral music is performed by an orchestra using Western instruments that are colloquially named »đội ›kèn Tây‹« (lit. band of »Western horns«) – the resultant hybrid between traditional rituals and Western music. In Rock Hà Nội, Bolero Sài Gòn, the composer and music historian Jason Gibbs posits that the influence of Western music in Vietnam came from 18th and 19th century Roman Catholic missionaries, who taught their congregation the basics of church music. Later, when »cải lương« – a form of folk theatre that grew out of »đờn ca tài tử« (lit. music of amateurs) in the Mekong Delta in the early 20th century – married the traditional pentatonic scale and Western instruments, the then-colonial power was also making efforts to popularise Western culture, notably musical theatre. Marches with lively, uplifting melodies such as »La Marseillaise,« incidentally the French national anthem, and »La Madelon« were loved by both the populace and younger generations of Vietnamese musicians. Brass instruments were thus introduced to the repertoire of Vietnamese music. The brass section of funeral orchestras often consists of ten musicians wearing formal attire, usually a suit or a dress shirt and tie, playing the drums, trumpet, saxophone, trombone etc., with strings rarely if at all included. For sizeable Southern funerals, the brass band may include up to 30 players, with the trumpet as the focal point of the musical arrangement and the remaining instruments as auxiliaries. This is a world apart from Northern »phường bát âm,« where wind instruments consist of the kèn bầu playing solo on a background of percussion and strings with the volume just so.

A performance by ‘Đội Kèn Tây' at a funeral in Kien Giang, a southern province of Mekong Delta

»Đội ›kèn Tây‹« often play tunes on request, meaning the family’s and visitors’ best-loved songs as well as the favourites of the deceased. Due to its »hospitable« nature, Southern funeral music reflects the taste of the general populace, especially the genres of lyrical love songs influenced by folk music that people often call »nhạc sến« (lit. cheesy music), Cuban bolero, or »nhạc vàng« (pre-war music; lit. golden music). The names of these genres are often used interchangeably even though they do have their differences. Nevertheless, they all rose to popularity among the youths of Saigon in the 1950s, when Latin music and dances such as rumba and bolero were introduced to the mainstream. Singers and musicians made Vietnamese versions of the lyrics on top of the vibrant rhythms of rumba and bolero, writing songs mainly about the love between couples, or family. This genre of music persisted because it suited the tastes of Southern listeners, though it was forced underground after 1975 due to a State ban. People then continued to casually listen to »nhạc vàng« and bolero within the confines of the family, or via musical concert series by the Vietnamese diasporic community such as Paris by Night, but for a few decades, during the official ban, these musics could only be played loudly and publicly for the »kèn Tây« ritual at funerals. According to this news clip, the Department of Culture and Information even issued a ban in 2000, prohibiting funeral bands from playing »nhạc vàng!« – though as with other music censorship laws, this law is not officially written into policy and enforcement is not uniform across the provinces.

»Đội Kèn Tây« playing revolutionary music based on the host’s request: the »Hát Mãi Khúc Quân Hành« (Singing Long Live Army March) and »Đoàn Vệ Quốc Quân« (Union of the National Defense Army). While popular funeral songs are about family and compassion, in this funeral, perhaps the deceased had worked in the army, as the songs requested have a heroic atmosphere and fast-paced rhythm.

Many similarities to the entertainment at funerals in Southern Vietnam with »Đội Kèn Tây« can be found in several different regions of the world. For example, the African-American community in New Orleans has a funeral jazz ceremony, from which artist collective The Propeller Group was inspired to create the work »The Living Need Light, The Dead Need Music« (2014) combining Vietnamese and Black American ritual music. In Taiwan, a women’s brass group named Xiu Juan Female Music Band has created an international fanbase in the recent decade. The group features young musicians wearing short pleated skirt uniforms that give performances similar to the entertaining parades at Vietnamese funerals.

Xiu Juan band performing brass music and a marching dance at a funeral in Taiwan

Regional differences exist in any country, and in any ritual or daily custom. When it comes to entertainment, Southern Vietnamese people only watch comedy shows from Saigon or Mekong Delta troupes and feel distant from Northern-style comedy because of its seriousness. Likewise Northern audiences do not like the comedy theater in the South as they consider it too superficial. But there is a Vietnamese proverb: »Respect in death is the final respect«[2]: all manner of pain and earthly emotions will be shaken off in death. The funeral, therefore, is the last chapter of one’s fate. We do not choose how we are born, and when we die, everything comes down to the family's choice of that final song with which to send us off. Families inherit customs from their places of origin, and nurture these within their own family story. Funeral music, then, is probably most closely linked to a specific place as well as one’s memories.

RESOURCES/ RECOMMENDED READING

Barley Norton. Songs for the Spirits – Music and Mediums in Modern Vietnam, e-book, University of Illinois, 2019.Craig Duncan, Saigon, East of New Orleans: The Surprising Global Roots of Vietnam's Funeral Marching Bands, on Saigoneer

Đức Thịnh Ngô. Lên đồng, hành trình của thần linh và thân phận (Len dong, journeys of spirits, bodies, and destinies), Nhà xuất bản Trẻ, 2008.

Jason Gibbs, Rock Hà Nội và Rumba Cửu Long, übersetzt von Nguyễn Trương Quý, NXB Tri thức, 2008.

Jason Gibbs, Nhìn lại quá trình kiểm duyệt nhạc Việt qua năm tháng (auf Vietnamesisch). An overview of music censorship in Vietnam through the time, im BBC.

A glossary of Vietnamese folk songs and traditional instruments (in Vietnamese)

[1] »Sống dầu đèn, chết kèn trống,« translated following the title of an artwork created by The Propeller Group in 2014.

[2] »Nghĩa tử là nghĩa tận«