Listening to Transient Labour in Singapore

Acoustic Lives of Migrant Workers

By Shzr Ee Tan with Suprihatin Nengsih, Rema Tabangcura, Jora Lyn Fallera Mounsel, Meikhan Sri Bandar, Beckerbone Millado, and Zakir Hossain Khokan, 2021-22The electronic faux-nature splash of a punishingly cheery wakeup call at 5 am on a mobile phone by her bedside is the first thing that jolts Meikhan Sri Bandar awake in Singapore everyday: it rouses her to begin her 17-hour day of fussing over somebody else’s breakfast, washing somebody else’s toilet, hoovering somebody else’s floor, and more. Meikhan, in her 40s, born in Indonesia, is one of 250,000 domestic workers currently active in Singapore.

»Because the sound of nature is mostly smooth and gentle. So when I am sleeping and need to wake up, when the ringtone comes on, it doesn’t shock me. But now there so many choices ringtones in nature!,« she explains of her music alarm over an exchange on Facebook messenger, an app whose (sometimes muted-on-vibration) pings she has learnt to listen to for social regulation of her day, even as numerous ambient and incidental sounds which many like her – and us – take for granted, as by-products of real activities, have come to take on new value over the course of a seven-day »sound diary« exercise.

For one week in November 2021, as part of a research project on Sounds of Precarious Labour, I (Shzr Ee Tan) invited six migrant workers in Singapore to share »sound stories« of their labour and leisure routines. We began by setting up »raw materials« and asking contributors to create daily logs on a sound diary, noting down everything and anything that crossed their aural consciousness – mundane or significant. Quick-and-dirty mobile-phone recordings or photographs were made where possible, supplementing their logs. Together with myself as an ethnomusicologist and facilitator then based in London, we sought to put together a multimedia mosaic for a piece of collaborative ethnography detailing the acoustic lives of migrant workers, in random and not-so-random »snapshots« and »soundshots.« What were people’s favourite sounds? What sounds were the most jarring? What sounds made the most impressions? Were there any sonic surprises?

Bangladeshi and Indian workers in the corridors of a hostel for migrant workers in Changi, Singapore. Photo: Shzr Ee Tan, 2021

What would an aural-centric exploration teach us, as seven individuals, six of whom place themselves/ourselves in the migrant worker community?

That sound and music were pulling a lot more weight than most people assumed, in the regimenting of migrant workers’ lives and labour, became absolutely clear to us. Each day often began for many workers via the beep of an alarm, or more often – a specially selected recording on their mobile phones. Sound – or music – was also often bookending the last conscious moments of a worker’s day as they/we shut their eyes for daily rest, some listening to a playlist of Islamic chant, others to Bollywood tunes – and yet others to the ambient whirr of an electric fan.

Throughout the course of a day, sonic-centric re-understandings of a »typical« day of labour also provide new insights on temporality, memory, power relations, different kinds of safe (sonic or otherwise) spaces, personal agency, and more. For example, many Mandarin-dubbed Korean TV drama dialogues on daytime television watched by the elderly parents of not a few Singaporean employers become a particular kind of imposed (but also useful) language lesson – and sometimes even entertainment, or an intergenerational and intercultural bonding experience – for many domestic workers who share the same aural spaces with other members of the household. The regular cries of schoolchildren heard from a nearby field mark the day in terms of specific recess times at 11 am and the daily breaking up of school at 1:40 pm. For a construction worker, it is the opposite that comes into play – the daytime sounds of piling and drilling on a building site are often so loud that a work-along »energy pump-up« playlist (such as K-pop or Bollywood tracks which domestic workers use) makes absolutely no sense. Muffling earphones are instead used as safety mechanisms protecting the hearing of Bangladeshi workers. And as each day comes to an end, the chirp of crickets at night in densely-populated but also highly-greened urban living spaces in Singapore may bring forth a memory of village life in rural Indonesia or Bangladesh.

However, many domestic workers prefer to leave their phones on silent mode when working at home. Many are hyper conscious of sonic -proxemic areas in their workplaces-as-living spaces, which now, thanks to pandemic work-from-home regimes serve quadruple functions as the intimate zones of living as well as labour for their employers. The irony is that often, an amplified vibration from a mobile phone placed on a table can be louder, decibel-wise, than the actual sounded adhan. The point, however, regarding sonic self-censorship as a matter of interpersonal and social carving out of boundaries (putting a phone on silent mode, or putting the phone in one’s pocket to dampen vibrations) will have been made.

The dynamics of politico-spatial and religious-spatial (given that most households are Chinese) negotiation play out in interesting sonic manifestations. Many domestic workers have developed new ways of listening, or new thresholds for ambient sonic attentiveness – particularly, in response to particular types of vibrations. A WhatsApp message signals differently from a Facebook notification, or a phone call, or an alarm. And in turn, through these new ways of listening, newer, subtler ways of living, working, being – sharing intimate space-as-workspaces – are made.

In one specific type of social exchange where Mandarin or a dialect is deliberately articulated in the presence of a domestic worker, however, language is used as a means of sonic exclusion. This often happens in the situation of discussions on private/money issues, or discussions about the domestic worker herself. Often, the worker will be in direct earshot of conversations but linguistically removed – theoretically – from lexical content. What emerges however, paradoxically, is how many domestic workers over time begin to understand lexical content anyway, as they cultivate instead new skills in listening for nuance in vocality or tone of voice. Even more interesting is how – for workers who have developed daytime relationships with (often, bored and sometimes lonely) grandparents in the family – they end up learning to communicate in Mandarin, Hokkien, Teochew, or Cantonese.

Where language-as-text is often signalled as one of the key expressions of ocular-centric hegemony, language-as-sound, and non-language in sound (eg tone of voice) provides different contexts and pathways for gaining new social understandings and discoveries of everyday living in micropolitical contexts.

Even here, a few surprises may still reveal themselves, showing transient workers to be extremely cosmopolitan and highly-networked consumers of global and regional culture. Many Indonesian workers, for example, are as much fans of K-pop boy/ girl bands and the latest hits from Bollywood as they are well-versed in contemporary and nostalgic Indonesian pop. In the same way, Filipina workers are also au fait with the latest Anglo-American hits as they are with »American oldies« and Tagalog songs (as Jora Lyn’s example below shows).

Sound has also come to play important roles in the religious sphere. Anecdotally speaking, both the Indonesian and Filipina workers we have consulted with in this project, and beyond, expressed a re-invigoration of their faith and sense of ethnic identity upon coming to work in Singapore. Here, many have reinforced their commitment to religion via musical and technological channels alongside physical attendance in mosques and churches. Devotional zikir/ nasyid chants performed by contemporary Islamic figures from religious preachers to Muslim boybands in Malaysia and charismatic Lebanese popstars operating out of Sweden (Mahir Zain) have entered the playlists of many Indonesian and Bangladeshi workers, even as small groups congregated in local mosques to rehearse their devotion in pre-pandemic times. Contemporary American, Australian, and Filipino Christian and Catholic praise songs are also well circulated in many Filipina networks, with live musical performance in church services and cellgroups supported and prefaced by the swapping of scores, lyrics, recordings, and mp3/mp4 files on WhatsApp and Facebook channels.

Collectively – as some of the stories below show – these musical bubbles and therapy zones provide valuable »time out,« self-care, and community bonding opportunities for migrant workers in Singapore.

Nengsih Suprihatin (with microphone) leading domestic worker members of the Nur Assyifa Islamic chant (nashid) group at a mosque in the Novena area, Singapore. Photo: Shzr Ee Tan, 2021

The putting together of this specific sound diary project, encompassing interviews with and contributions from key individuals below, was supported by Nusasonic and the Goethe-Institut.

Academic facilitator and ethnomusicologist Shzr Ee Tan, active in London and Singapore, at first began coordinating the sound diary exercise virtually in the wake of pandemic-impacted limitations on face-to-face events. Follow-up sessions and interviews were then made – and are still ongoing – in Singapore.

Over the course of working together, meta lessons have also been learnt. Maintaining a 17-hour sound diary on top of trying to perform a full day of housekeeping and care work often becomes an extra tax on the labour of migrant workers. As collaborators we have been flexible with the partial completion and/ or curated selection of particular examples which we share below. What is interesting is how choices over the final sound recordings to be featured are individually, collectively, and editorially presented. Participants also received a small honorarium for their contributions.

A second, more revelatory lesson learnt was how digital technology – enabled over mobile phone interfaces, high-speed wifi connections in employer homes, plus a grounded/ »underground« understanding of freeware via »life hacking« cheap or freeware tech tools – has been and continues to be crucial to the social networking of migrant workers. Given the already physically and geographically restricted movements of migrant workers pre-pandemic, many had already been channelled into finding internet and technology-based community-building and social exchange solutions well before various national and global agencies began making the big pivot towards tech-enabled solutions during lockdowns at the height of Covid. In a sense, migrant workers were already »ahead of the tech game.«

What is interesting is how consciously music, labour-generated sound, and environmental acoustics can be re-understood as playing important live, recorded, mediated, face-to-face, as well as online roles in the disciplining, framing, enabling, support, and encouragement of the lives, labour, and leisure of migrant workers.

We proceed to share separate transcripts in the rich varieties of diverse English, and the personal recordings selected by our six migrant worker participants below.

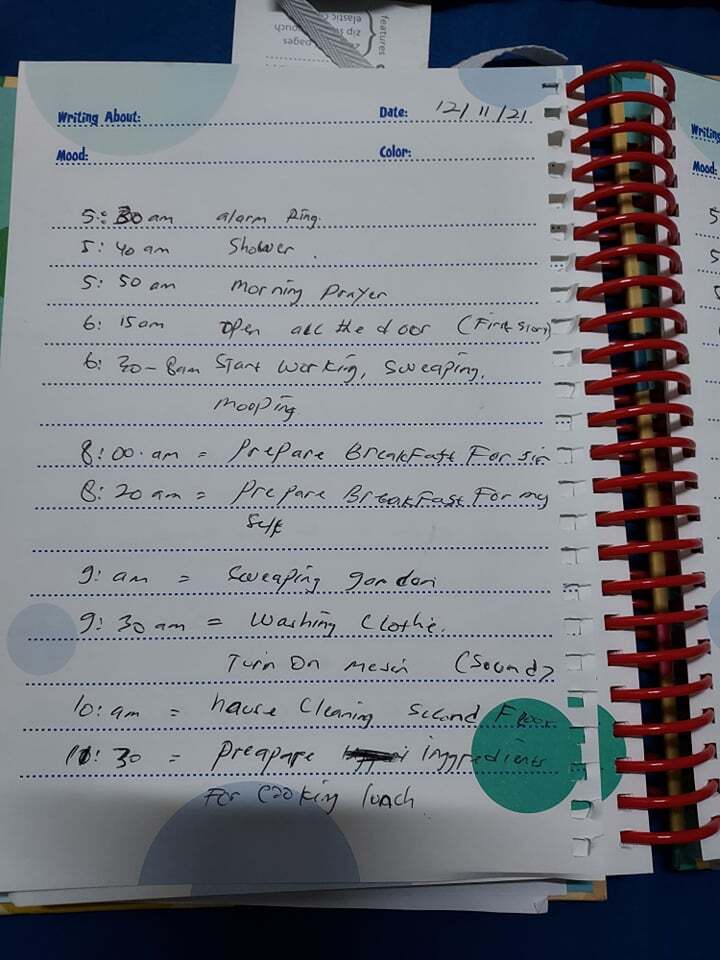

View of a day’s entry in Neng’s diary. Photo: Nengsih Suprihatin, 2021

Neng’s diary (excerpted below) gives us a sense of a typical weekday routine expressed through sound. Her sonic moments of labour range from the sweeping of backyards (you can hear the dry leaves crunching) to the visceral sizzle of oil in a pan. Her recordings tell us of the sensorial dimensions of household routines we often take for granted. An avid cook, some of the highlights of Neng’s sound diary include the practised and virtuoso chopping and scratching-off of garlic on a board, and the frisson of beans being sautéed in a pan.

In her own words: My name is Suprihatin Nengsih. I was born in Serang – Banten province Indonesia. I have been working in Singapore since 2007 with one employer. I am the founder of PIS NUR ASSYFA, a devotional chanting group for Muslim women since August 17, 2015. And I was the group leader from 2015 to 2018. I have also been active with Migrant Writers Singapore, and have joined blood donation activities since 2018 – 2021.

My motto in life is to never be ashamed of what you feel, you have the right to feel any emotion that you want, and to do what makes you happy.

5.30 am: Alarm Ring

5.40 am: Shower

5.50 am: Morning Prayer

6.15 am: Open [turn on] A/C the door (first story)

6.30 – 8.00 am: Start working, sweeping, mopping

8.00 am: Prepare breakfast for Sir

8.20 am: Prepare breakfast for myself

9.00 am: Sweeping garden

9.30 am: Washing clothes, turn on mesen [machine] sounds

10.00 am House cleaning second floor

10.30 am: Prepare ingredients for cooking lunch

12.00 pm: Cooking lunch (cooking sounds)

13.00 pm: Lunch, afternoon prayer, rest

15.00 pm: Prepare ingredients for cooking dinner

16.00 pm: Watering the plants

17.30 pm: Start cooking (cooking sounds)

18.30 pm: Wet kitchen cleaning

19.00 pm: Dinner

20.30 pm: Washing dishes/ throw out rubbish

21.00 pm: Exercise

22.00 pm: Shower/ take rest

Rema’s diary brings up sonic threads which connect sounds of the Singaporean environment – in a domestic household, and also of the weather at large – with personal memories, via acoustic moments of her life and aspirations in the Philippines. In one particular clip which features her wiping down dishes after washing them she also reveals how sonic management and space-negotiation in a Singaporean household has subtle impact on her labour and relations with her employer. We share verbatim transcripts of her diary accompanying her sound files.

In her own words: I'm Rema Tabangcura, 41 years old and mother of 2 boys. Working as a domestic helper here in Singapore for 10 years. I love to read and write. I'm a volunteer at Uplifters, a nonprofit organisation offering a free online course on money management, mental well-being, and personal growth.

Sunday Nov 07, 2021: My off day in Botanic Gardens, I recorded the sound of the waterfalls, I always love the waterfall, it was amazing. It’s going to rain so there’s thunder. WATERFALLS!

Monday Nov 08. 2021: I record this while taking shower, as I said I love the sound of water. WATER TAP – SHOWER!

November 08, 2021: While brushing and washing rags. I used to wash them by hand way back home, and I used to brush them too. Doing this reminds me of one of my tasks when I was a child washing clothes, sometimes along the river.

November 08, 2021: While vacuuming, I love the sound of the vacuum. I like the sound of the vacuum sucking the dirt. And plan to buy one to bring back home. I can suck all the unseen dirt.

November 08, 2021: I am a housemaid so all I can record are my daily tasks on the phone I’m using. This sound is when the washing machine is on.

November 08, 2021: Yaayy!! Cooking time, I love cooking and since I’m frying fish today, gotta record it.

Frying fish. Photo: Rema Tabangcura, 2021

Nov 8, 2021: Drying plates and bowls. My madam was annoyed when I pile the plates loudly like it’s breaking, but what can I do…

Nov 9, 2021: On the road, a motorcycle sound on the way to the market. It reminds me of my son who loves to ride the motorcycle. He used to compete, I feel nervous when he told me he has a competition. Can’t do anything but to pray for his safety as it was his hobby and he loves it!

Nov 09 2021: Sounds of cars, can’t record much as I’m holding my groceries.

Nov 09, 2021: This was the sound of the water from a canal on the way home.

RAINDROPS: Every time it rains, my mind is at home in Philippines. Farming is our main source of income, so rain or shine we have to be on the farm. It’s nice when it rains, as it cools down. Not good when rains nonstop coz our area is prone to floods.

Raindrops falling down a roof ledge over a patio. Photo: Rema Tabangcura, 2021.

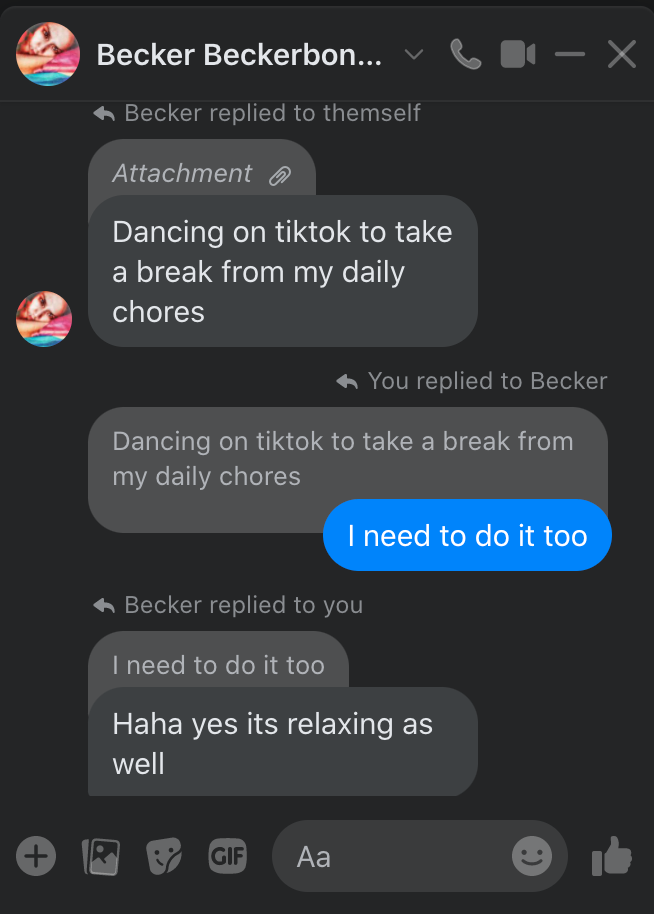

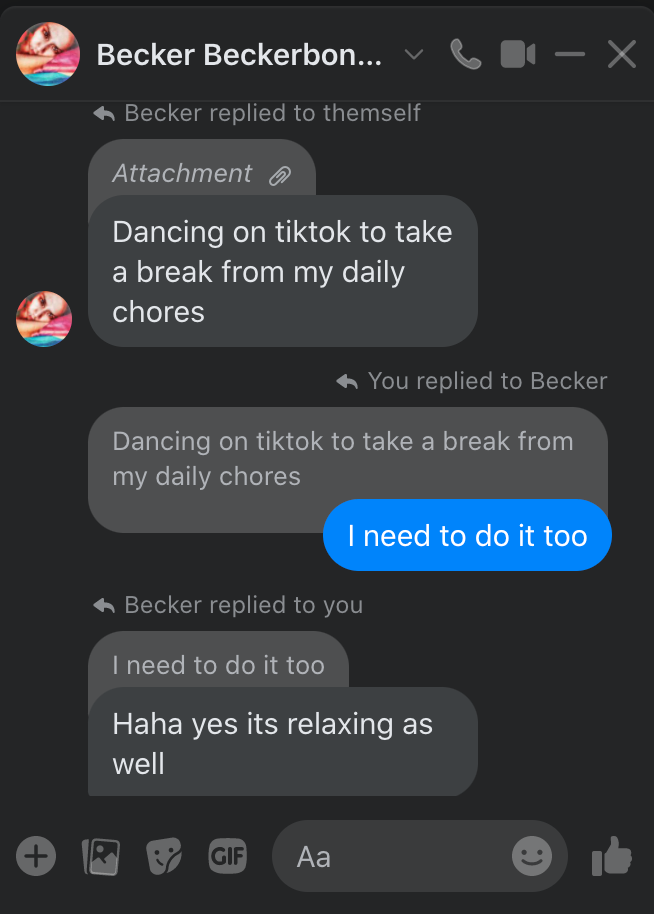

Beckerbone’s picks make an eclectic mix of the indisputably mundane – a doorknob clicking, a coffee machine expelling liquid, mahjong tiles rising from a mechanical desk – with consciously and carefully chosen music tracks: a Filipino boy band for a dance-at-home routine. In their short spurts of groove and action, her sound clips are almost meme-like in their expending of little bursts of energy. We share Facebook screengrabs of a conversation around some of her chosen sound clips below, and note how some of her contextualisations are deeply evocative.

In her own words: Olivetti M. Millado, born in Zambales, a single mother of five. She is known as BeckerBeckerbone OFW in Singapore. She has contributed some of her poems in various books and ebooks in the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Singapore. She was one of the finalists of Migrant Poetry Competitions in Dec 2017, 2019, 2021 and received an Honourable Mention. A finalist in the 2021 Mental Health Awareness Poem Writing Competition by Singapore Red Cross, she is the first Filipino poet to win and write 100 poems a day in a private group of poets in the Philippines. She also contributed to the Translating Migrant ebook, writing poetry and short stories. Beckerbone always goes by her own saying »For every of my written verses, there is love.«

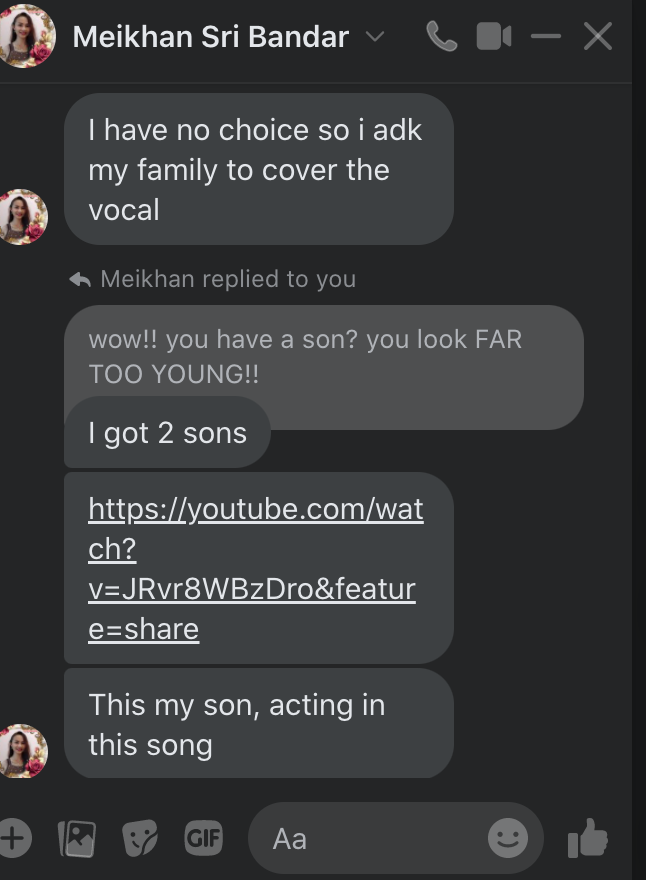

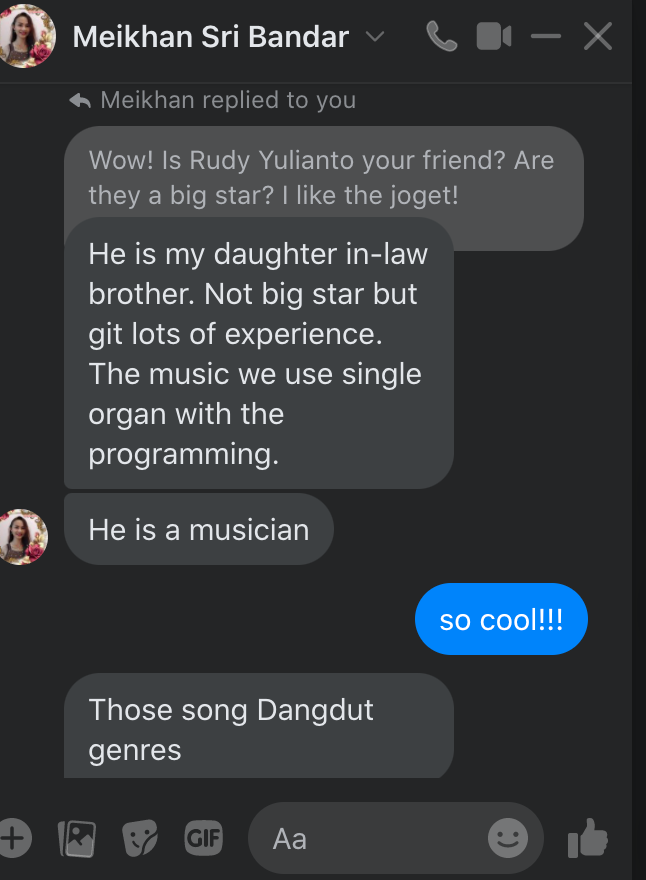

Meikhan’s account provides for a rich and deeply felt observation of everyday sounds heard in Singapore, correlated with special memories of her hometown in Indonesia. In the course of our collaborative chat over putting this story together, we also discovered that she is an active recording artist in Indonesia, and hails from a family of dangdut singers who have released multiple albums. We share a video of Meikhan singing here, and also links on YouTube to a few tracks featuring her sons and daughter-in-law . We also share some screengrabs of our conversations about her dangdut and campursari tracks.

In her own words: Meikhan Sri Bandar is from Batang, Jawa Tengah / Central Java, Indonesia. I came to Singapore end of January 2003. I am working in a Chinese Singaporean family, my first and only employer until now. My hobby is singing, dangdut and Javanese songs (campursari), second interest is writing short stories, poems. I have published anthologies in a book, and some song lyrics. I have 11 songs already published by July 2016.

1. What are your favourite sounds and why?

The little bird chirping on the curry tree is my favourite sound. Reminds me of when I was small, behind my house there was a coffee tree growing, and the little birds were always there morning or evening.

2. What are the sounds that were most annoying/that you dislike, and why?

The morning alarm ringing, when I am in the bathroom, because I had forgotten to off it before I go down from the bed. Also, the sounds of the kitchen filter absorbing the smoke when I am cooking.

3. Any surprising sounds?

Cricket (jangkrik) an insect related to the grasshoppers. The male produces a characteristic rhythmical chirping sound. This morning I was opening the bathroom door, I heard the cricket chirping, but I didn't see where’s it. I stood up try to find and was listening. I open the tap and the water flowed, and the cricket sound stop immediately.

Also, thunder: Actually I am not surprised but I was so shocked. Few years ago, I was alone at home, it was heavy rains and the lightning so scary. Suddenly the thunder blast so loud and the car parking in front the house, the alarm came suddenly noisy. I was so scared.

4. Any sounds that reminded you of your home/ travels?

The aeroplanes, when go home I go by airplane. The motorbike – in my village, motorbike is the most common transportation there, almost every house got 1 or 2 or 3 motorbikes. The sound almost all the time I heard in my home country.

5. Sounds you will remember forever?

My employer and their family’s voices. Especially the way they call my name. They have different intonations. Little birds chirping, the bells hang up on the windows, the sounds are so artistic.

Youtube links to Meikhan’s family who are bona fide campusari performers with recorded albums on Youtube:

MSB Aku Tak Mengapa

MSB Goyang Asoy

Tongkat Dan Batu

MSB Cinta Terhalang

Jora Lyn’s diary evokes much sentiment, feeling, and poetry, where day-to-day chores connect to specific moments and memories she has kept close to her heart even as she lives far removed from her family in the Philippines. A hearty consumer of Anglo-American and Filipino pop, Jora Lyn also listens to music to relax and put herself into hopeful moods. Her choice of music here is Engelbert Humperdinck’s cover of Charles Aznavour’s »She.«

In her own words: Joralyn Fallera Mounsel was born and raised in North Cotabato Philippines but moved to the South when she was 22. She is 31 years old, a domestic worker in Singapore for almost 6 years. She writes poems and short stories and loves music too.

1. What sounds do you not like to hear?

Beeping alarm I think this is the most annoying sound, especially if I slept so late last night and I needed to wake up early the next morning.

2. What is your favourite sound?

Music – I love to listen to music because it elevates my mood, makes me feel lighter and stress free, and makes me even happier.

3. What is the most surprising sound?

Heavy rain and thunder: the sudden roar of the thunder in the heavy rain made me jump. So I think it’s the most surprising ☺

4. What sounds bring back memories?

The sound of the kitchen wares: it reminds me of a wonderful time spent with my family as we had our meal together everytime I come back to the Philippines. And these memories remain in my mind forever. It’s what I always look forward to every holiday but now can’t go cos covid outbreak.

The sound from nature: the sound of nature reminds me more of home. The calming sound of the wind as it blew the tree leaves and the singing little birds sounded so calming but it makes me reminisce about my life back home.

Birds: went out earlier and spotted this flock of birds in a tree… like feasting ☺

Zakir, the only male participant in this collaborative ethnography, presents a very different picture of the acoustic life of migrant workers in Singapore. His huge recording files – some lasting as long as three hours at a stretch – provide a rich and beautiful soundtrack which allows the observer, unencumbered by visuals, plentiful opportunities for rich imagination.

We can hear close and distant traffic on the expressway – as workers get ready to move onto the backs of lorries chugging up when groups of Bangladeshi builders leave their hostels for the construction sites of their workplaces. Snippets of conversation – instructions from Singaporean Chinese contractors – interweave between sounds of a worksite; the screen of welding, the fizz soldering, the whirr of a saw, piling; heavy lifting of steel, bricks, and mortar.

Here and there, we catch lift doors opening and closing to the familiar ping of floor arrivals, plus random transport announcements on the Mass Rapid Transit system. We also catch chatter among workers in Bengali as they discuss particular job procedures alongside (later) gossip and food. Beyond the obvious activity-centred and linear expressions of sound passing through time, we are also able to listen for space – the sputter of an engine up close in the humid outdoors, the sense of cavernous space as voices echo in what must be a giant construction arena; the sound of unknown, mysterious objects being shuffled around in a dry, enclosed indoor space.

In his own words: Amrakajona Zakir Hossain Khokan is a community organizer and change maker. He and a migrant local volunteer team have been raising awareness, promoting diversity, and empowering migrant communities through literature, reading, photography, film, blood donation drives, book fairs, panel discussions, human libraries, stage poetry plays, art exhibitions, book publishing, and other art activities from Migrant Writers of Singapore or Bangladesh Book Fair; Singapore, to One Bag One Book and Migrant Worker Photography Festival. Zakir is an award-winning poet and a quality control project coordinator in the construction sector.

Q: Any sounds that remind you of your home?

A: The sound of my son calling be Abby

Q: Sounds you will remember forever?

A: The voice of my father. How he called my name - Khokan.

For one week in November 2021, as part of a research project on Sounds of Precarious Labour, I (Shzr Ee Tan) invited six migrant workers in Singapore to share »sound stories« of their labour and leisure routines. We began by setting up »raw materials« and asking contributors to create daily logs on a sound diary, noting down everything and anything that crossed their aural consciousness – mundane or significant. Quick-and-dirty mobile-phone recordings or photographs were made where possible, supplementing their logs. Together with myself as an ethnomusicologist and facilitator then based in London, we sought to put together a multimedia mosaic for a piece of collaborative ethnography detailing the acoustic lives of migrant workers, in random and not-so-random »snapshots« and »soundshots.« What were people’s favourite sounds? What sounds were the most jarring? What sounds made the most impressions? Were there any sonic surprises?

Bangladeshi and Indian workers in the corridors of a hostel for migrant workers in Changi, Singapore. Photo: Shzr Ee Tan, 2021

Acoustic framings of everyday life: Reunderstanding the world through sound

Our project together draws inspiration from the by-now classic proposition by audioculture theorist Jonathan Sterne (1999, 2001) that a shift away from ocular-centrism, ie visually dominated (including text-based) sensorial understandings of the world, could bring us new revelations and insights on how we live, work, and play. In so doing, we also take a leaf out of Steven Feld’s (1994) approach of acoustemology, whereby acts of listening and sounding become particular ways of knowing the world.What would an aural-centric exploration teach us, as seven individuals, six of whom place themselves/ourselves in the migrant worker community?

That sound and music were pulling a lot more weight than most people assumed, in the regimenting of migrant workers’ lives and labour, became absolutely clear to us. Each day often began for many workers via the beep of an alarm, or more often – a specially selected recording on their mobile phones. Sound – or music – was also often bookending the last conscious moments of a worker’s day as they/we shut their eyes for daily rest, some listening to a playlist of Islamic chant, others to Bollywood tunes – and yet others to the ambient whirr of an electric fan.

Throughout the course of a day, sonic-centric re-understandings of a »typical« day of labour also provide new insights on temporality, memory, power relations, different kinds of safe (sonic or otherwise) spaces, personal agency, and more. For example, many Mandarin-dubbed Korean TV drama dialogues on daytime television watched by the elderly parents of not a few Singaporean employers become a particular kind of imposed (but also useful) language lesson – and sometimes even entertainment, or an intergenerational and intercultural bonding experience – for many domestic workers who share the same aural spaces with other members of the household. The regular cries of schoolchildren heard from a nearby field mark the day in terms of specific recess times at 11 am and the daily breaking up of school at 1:40 pm. For a construction worker, it is the opposite that comes into play – the daytime sounds of piling and drilling on a building site are often so loud that a work-along »energy pump-up« playlist (such as K-pop or Bollywood tracks which domestic workers use) makes absolutely no sense. Muffling earphones are instead used as safety mechanisms protecting the hearing of Bangladeshi workers. And as each day comes to an end, the chirp of crickets at night in densely-populated but also highly-greened urban living spaces in Singapore may bring forth a memory of village life in rural Indonesia or Bangladesh.

The adhan in your pocket: Spatial negotiations and muted vibrations

The adhan is an interesting case to consider in acoustemological terms. Frequently heard throughout Islamic parts of Southeast Asia as a matter of public broadcasts from minaret loudspeakers, and often in multiple and simultaneous renditions, as played from mosques in Singapore, the Islamic call to prayer is considerably muted through careful sociocultural and sociopolitical engineering of public and community spaces (Lee 1999). For audible and regular reminders to prostrate and pray, most Indonesian migrant workers (as well as Singaporean Muslims) rely instead on downloaded adhan apps on their phones.However, many domestic workers prefer to leave their phones on silent mode when working at home. Many are hyper conscious of sonic -proxemic areas in their workplaces-as-living spaces, which now, thanks to pandemic work-from-home regimes serve quadruple functions as the intimate zones of living as well as labour for their employers. The irony is that often, an amplified vibration from a mobile phone placed on a table can be louder, decibel-wise, than the actual sounded adhan. The point, however, regarding sonic self-censorship as a matter of interpersonal and social carving out of boundaries (putting a phone on silent mode, or putting the phone in one’s pocket to dampen vibrations) will have been made.

The dynamics of politico-spatial and religious-spatial (given that most households are Chinese) negotiation play out in interesting sonic manifestations. Many domestic workers have developed new ways of listening, or new thresholds for ambient sonic attentiveness – particularly, in response to particular types of vibrations. A WhatsApp message signals differently from a Facebook notification, or a phone call, or an alarm. And in turn, through these new ways of listening, newer, subtler ways of living, working, being – sharing intimate space-as-workspaces – are made.

Linguistic exclusion as sonic exclusion

Another interesting case study is that of how language is used in a (usually Chinese Singaporean) household with a domestic worker. For many Singaporean families, English – with a splattering of the odd Bahasa or Tagalog phrase – is used by Singaporean employers with domestic workers as the base language for instruction and communication. In intergenerational exchanges between employers and their live-in parents, however, Mandarin – or a dialect of – is often deployed.In one specific type of social exchange where Mandarin or a dialect is deliberately articulated in the presence of a domestic worker, however, language is used as a means of sonic exclusion. This often happens in the situation of discussions on private/money issues, or discussions about the domestic worker herself. Often, the worker will be in direct earshot of conversations but linguistically removed – theoretically – from lexical content. What emerges however, paradoxically, is how many domestic workers over time begin to understand lexical content anyway, as they cultivate instead new skills in listening for nuance in vocality or tone of voice. Even more interesting is how – for workers who have developed daytime relationships with (often, bored and sometimes lonely) grandparents in the family – they end up learning to communicate in Mandarin, Hokkien, Teochew, or Cantonese.

Where language-as-text is often signalled as one of the key expressions of ocular-centric hegemony, language-as-sound, and non-language in sound (eg tone of voice) provides different contexts and pathways for gaining new social understandings and discoveries of everyday living in micropolitical contexts.

Hermetically-sealed sonic spaces as self-care

A final example of the acoustic structuring of the lives of migrant workers as individuals, and also in different communities, can be found in the most obvious category of music – as self-care, affective labour, and also affective leisure. By this, we are referring to how streaming playlists or downloaded mp3 files for instance are consciously or ambiently played over earphones or mobile phone speakers. These musical articulations and active listenings support the physical rhythms of housework, or provide aural comfort and relief after a hard day of toil, or set up a de facto hermetically-sealed »safe space« for religious meditation by migrant workers, with the »outside world« screened off by earphones (echoing Bull 2001).Even here, a few surprises may still reveal themselves, showing transient workers to be extremely cosmopolitan and highly-networked consumers of global and regional culture. Many Indonesian workers, for example, are as much fans of K-pop boy/ girl bands and the latest hits from Bollywood as they are well-versed in contemporary and nostalgic Indonesian pop. In the same way, Filipina workers are also au fait with the latest Anglo-American hits as they are with »American oldies« and Tagalog songs (as Jora Lyn’s example below shows).

Sound has also come to play important roles in the religious sphere. Anecdotally speaking, both the Indonesian and Filipina workers we have consulted with in this project, and beyond, expressed a re-invigoration of their faith and sense of ethnic identity upon coming to work in Singapore. Here, many have reinforced their commitment to religion via musical and technological channels alongside physical attendance in mosques and churches. Devotional zikir/ nasyid chants performed by contemporary Islamic figures from religious preachers to Muslim boybands in Malaysia and charismatic Lebanese popstars operating out of Sweden (Mahir Zain) have entered the playlists of many Indonesian and Bangladeshi workers, even as small groups congregated in local mosques to rehearse their devotion in pre-pandemic times. Contemporary American, Australian, and Filipino Christian and Catholic praise songs are also well circulated in many Filipina networks, with live musical performance in church services and cellgroups supported and prefaced by the swapping of scores, lyrics, recordings, and mp3/mp4 files on WhatsApp and Facebook channels.

Collectively – as some of the stories below show – these musical bubbles and therapy zones provide valuable »time out,« self-care, and community bonding opportunities for migrant workers in Singapore.

Nengsih Suprihatin (with microphone) leading domestic worker members of the Nur Assyifa Islamic chant (nashid) group at a mosque in the Novena area, Singapore. Photo: Shzr Ee Tan, 2021

Final notes

The putting together of this specific sound diary project, encompassing interviews with and contributions from key individuals below, was supported by Nusasonic and the Goethe-Institut.Academic facilitator and ethnomusicologist Shzr Ee Tan, active in London and Singapore, at first began coordinating the sound diary exercise virtually in the wake of pandemic-impacted limitations on face-to-face events. Follow-up sessions and interviews were then made – and are still ongoing – in Singapore.

Over the course of working together, meta lessons have also been learnt. Maintaining a 17-hour sound diary on top of trying to perform a full day of housekeeping and care work often becomes an extra tax on the labour of migrant workers. As collaborators we have been flexible with the partial completion and/ or curated selection of particular examples which we share below. What is interesting is how choices over the final sound recordings to be featured are individually, collectively, and editorially presented. Participants also received a small honorarium for their contributions.

A second, more revelatory lesson learnt was how digital technology – enabled over mobile phone interfaces, high-speed wifi connections in employer homes, plus a grounded/ »underground« understanding of freeware via »life hacking« cheap or freeware tech tools – has been and continues to be crucial to the social networking of migrant workers. Given the already physically and geographically restricted movements of migrant workers pre-pandemic, many had already been channelled into finding internet and technology-based community-building and social exchange solutions well before various national and global agencies began making the big pivot towards tech-enabled solutions during lockdowns at the height of Covid. In a sense, migrant workers were already »ahead of the tech game.«

What is interesting is how consciously music, labour-generated sound, and environmental acoustics can be re-understood as playing important live, recorded, mediated, face-to-face, as well as online roles in the disciplining, framing, enabling, support, and encouragement of the lives, labour, and leisure of migrant workers.

We proceed to share separate transcripts in the rich varieties of diverse English, and the personal recordings selected by our six migrant worker participants below.

Neng’s World

View of a day’s entry in Neng’s diary. Photo: Nengsih Suprihatin, 2021Neng’s diary (excerpted below) gives us a sense of a typical weekday routine expressed through sound. Her sonic moments of labour range from the sweeping of backyards (you can hear the dry leaves crunching) to the visceral sizzle of oil in a pan. Her recordings tell us of the sensorial dimensions of household routines we often take for granted. An avid cook, some of the highlights of Neng’s sound diary include the practised and virtuoso chopping and scratching-off of garlic on a board, and the frisson of beans being sautéed in a pan.

In her own words: My name is Suprihatin Nengsih. I was born in Serang – Banten province Indonesia. I have been working in Singapore since 2007 with one employer. I am the founder of PIS NUR ASSYFA, a devotional chanting group for Muslim women since August 17, 2015. And I was the group leader from 2015 to 2018. I have also been active with Migrant Writers Singapore, and have joined blood donation activities since 2018 – 2021.

My motto in life is to never be ashamed of what you feel, you have the right to feel any emotion that you want, and to do what makes you happy.

5.30 am: Alarm Ring

5.40 am: Shower

5.50 am: Morning Prayer

6.15 am: Open [turn on] A/C the door (first story)

6.30 – 8.00 am: Start working, sweeping, mopping

8.00 am: Prepare breakfast for Sir

8.20 am: Prepare breakfast for myself

9.00 am: Sweeping garden

9.30 am: Washing clothes, turn on mesen [machine] sounds

10.00 am House cleaning second floor

10.30 am: Prepare ingredients for cooking lunch

12.00 pm: Cooking lunch (cooking sounds)

13.00 pm: Lunch, afternoon prayer, rest

15.00 pm: Prepare ingredients for cooking dinner

16.00 pm: Watering the plants

17.30 pm: Start cooking (cooking sounds)

18.30 pm: Wet kitchen cleaning

19.00 pm: Dinner

20.30 pm: Washing dishes/ throw out rubbish

21.00 pm: Exercise

22.00 pm: Shower/ take rest

Rema’s Sound Diary

Rema Tabangcura’s selfie, 2021Rema’s diary brings up sonic threads which connect sounds of the Singaporean environment – in a domestic household, and also of the weather at large – with personal memories, via acoustic moments of her life and aspirations in the Philippines. In one particular clip which features her wiping down dishes after washing them she also reveals how sonic management and space-negotiation in a Singaporean household has subtle impact on her labour and relations with her employer. We share verbatim transcripts of her diary accompanying her sound files.

In her own words: I'm Rema Tabangcura, 41 years old and mother of 2 boys. Working as a domestic helper here in Singapore for 10 years. I love to read and write. I'm a volunteer at Uplifters, a nonprofit organisation offering a free online course on money management, mental well-being, and personal growth.

Sunday Nov 07, 2021: My off day in Botanic Gardens, I recorded the sound of the waterfalls, I always love the waterfall, it was amazing. It’s going to rain so there’s thunder. WATERFALLS!

Monday Nov 08. 2021: I record this while taking shower, as I said I love the sound of water. WATER TAP – SHOWER!

November 08, 2021: While brushing and washing rags. I used to wash them by hand way back home, and I used to brush them too. Doing this reminds me of one of my tasks when I was a child washing clothes, sometimes along the river.

November 08, 2021: While vacuuming, I love the sound of the vacuum. I like the sound of the vacuum sucking the dirt. And plan to buy one to bring back home. I can suck all the unseen dirt.

November 08, 2021: I am a housemaid so all I can record are my daily tasks on the phone I’m using. This sound is when the washing machine is on.

November 08, 2021: Yaayy!! Cooking time, I love cooking and since I’m frying fish today, gotta record it.

Frying fish. Photo: Rema Tabangcura, 2021

Nov 8, 2021: Drying plates and bowls. My madam was annoyed when I pile the plates loudly like it’s breaking, but what can I do…

Nov 9, 2021: On the road, a motorcycle sound on the way to the market. It reminds me of my son who loves to ride the motorcycle. He used to compete, I feel nervous when he told me he has a competition. Can’t do anything but to pray for his safety as it was his hobby and he loves it!

Nov 09 2021: Sounds of cars, can’t record much as I’m holding my groceries.

Nov 09, 2021: This was the sound of the water from a canal on the way home.

RAINDROPS: Every time it rains, my mind is at home in Philippines. Farming is our main source of income, so rain or shine we have to be on the farm. It’s nice when it rains, as it cools down. Not good when rains nonstop coz our area is prone to floods.

Raindrops falling down a roof ledge over a patio. Photo: Rema Tabangcura, 2021.

Beckerbone’s picks

Beckerbone’s picks make an eclectic mix of the indisputably mundane – a doorknob clicking, a coffee machine expelling liquid, mahjong tiles rising from a mechanical desk – with consciously and carefully chosen music tracks: a Filipino boy band for a dance-at-home routine. In their short spurts of groove and action, her sound clips are almost meme-like in their expending of little bursts of energy. We share Facebook screengrabs of a conversation around some of her chosen sound clips below, and note how some of her contextualisations are deeply evocative.

In her own words: Olivetti M. Millado, born in Zambales, a single mother of five. She is known as BeckerBeckerbone OFW in Singapore. She has contributed some of her poems in various books and ebooks in the Philippines, Hong Kong, and Singapore. She was one of the finalists of Migrant Poetry Competitions in Dec 2017, 2019, 2021 and received an Honourable Mention. A finalist in the 2021 Mental Health Awareness Poem Writing Competition by Singapore Red Cross, she is the first Filipino poet to win and write 100 poems a day in a private group of poets in the Philippines. She also contributed to the Translating Migrant ebook, writing poetry and short stories. Beckerbone always goes by her own saying »For every of my written verses, there is love.«

Meikhan’s secret singing star history

Meikhan’s account provides for a rich and deeply felt observation of everyday sounds heard in Singapore, correlated with special memories of her hometown in Indonesia. In the course of our collaborative chat over putting this story together, we also discovered that she is an active recording artist in Indonesia, and hails from a family of dangdut singers who have released multiple albums. We share a video of Meikhan singing here, and also links on YouTube to a few tracks featuring her sons and daughter-in-law . We also share some screengrabs of our conversations about her dangdut and campursari tracks. In her own words: Meikhan Sri Bandar is from Batang, Jawa Tengah / Central Java, Indonesia. I came to Singapore end of January 2003. I am working in a Chinese Singaporean family, my first and only employer until now. My hobby is singing, dangdut and Javanese songs (campursari), second interest is writing short stories, poems. I have published anthologies in a book, and some song lyrics. I have 11 songs already published by July 2016.

1. What are your favourite sounds and why?

The little bird chirping on the curry tree is my favourite sound. Reminds me of when I was small, behind my house there was a coffee tree growing, and the little birds were always there morning or evening.

2. What are the sounds that were most annoying/that you dislike, and why?

The morning alarm ringing, when I am in the bathroom, because I had forgotten to off it before I go down from the bed. Also, the sounds of the kitchen filter absorbing the smoke when I am cooking.

3. Any surprising sounds?

Cricket (jangkrik) an insect related to the grasshoppers. The male produces a characteristic rhythmical chirping sound. This morning I was opening the bathroom door, I heard the cricket chirping, but I didn't see where’s it. I stood up try to find and was listening. I open the tap and the water flowed, and the cricket sound stop immediately.

Also, thunder: Actually I am not surprised but I was so shocked. Few years ago, I was alone at home, it was heavy rains and the lightning so scary. Suddenly the thunder blast so loud and the car parking in front the house, the alarm came suddenly noisy. I was so scared.

4. Any sounds that reminded you of your home/ travels?

The aeroplanes, when go home I go by airplane. The motorbike – in my village, motorbike is the most common transportation there, almost every house got 1 or 2 or 3 motorbikes. The sound almost all the time I heard in my home country.

5. Sounds you will remember forever?

My employer and their family’s voices. Especially the way they call my name. They have different intonations. Little birds chirping, the bells hang up on the windows, the sounds are so artistic.

Youtube links to Meikhan’s family who are bona fide campusari performers with recorded albums on Youtube:

MSB Aku Tak Mengapa

MSB Goyang Asoy

Tongkat Dan Batu

MSB Cinta Terhalang

Jora Lyn’s tracks

Jora Lyn’s diary evokes much sentiment, feeling, and poetry, where day-to-day chores connect to specific moments and memories she has kept close to her heart even as she lives far removed from her family in the Philippines. A hearty consumer of Anglo-American and Filipino pop, Jora Lyn also listens to music to relax and put herself into hopeful moods. Her choice of music here is Engelbert Humperdinck’s cover of Charles Aznavour’s »She.« In her own words: Joralyn Fallera Mounsel was born and raised in North Cotabato Philippines but moved to the South when she was 22. She is 31 years old, a domestic worker in Singapore for almost 6 years. She writes poems and short stories and loves music too.

1. What sounds do you not like to hear?

Beeping alarm I think this is the most annoying sound, especially if I slept so late last night and I needed to wake up early the next morning.

2. What is your favourite sound?

Music – I love to listen to music because it elevates my mood, makes me feel lighter and stress free, and makes me even happier.

3. What is the most surprising sound?

Heavy rain and thunder: the sudden roar of the thunder in the heavy rain made me jump. So I think it’s the most surprising ☺

4. What sounds bring back memories?

The sound of the kitchen wares: it reminds me of a wonderful time spent with my family as we had our meal together everytime I come back to the Philippines. And these memories remain in my mind forever. It’s what I always look forward to every holiday but now can’t go cos covid outbreak.

The sound from nature: the sound of nature reminds me more of home. The calming sound of the wind as it blew the tree leaves and the singing little birds sounded so calming but it makes me reminisce about my life back home.

Birds: went out earlier and spotted this flock of birds in a tree… like feasting ☺

Zakir’s marathon soundtracks

Zakir, the only male participant in this collaborative ethnography, presents a very different picture of the acoustic life of migrant workers in Singapore. His huge recording files – some lasting as long as three hours at a stretch – provide a rich and beautiful soundtrack which allows the observer, unencumbered by visuals, plentiful opportunities for rich imagination.

We can hear close and distant traffic on the expressway – as workers get ready to move onto the backs of lorries chugging up when groups of Bangladeshi builders leave their hostels for the construction sites of their workplaces. Snippets of conversation – instructions from Singaporean Chinese contractors – interweave between sounds of a worksite; the screen of welding, the fizz soldering, the whirr of a saw, piling; heavy lifting of steel, bricks, and mortar.

Here and there, we catch lift doors opening and closing to the familiar ping of floor arrivals, plus random transport announcements on the Mass Rapid Transit system. We also catch chatter among workers in Bengali as they discuss particular job procedures alongside (later) gossip and food. Beyond the obvious activity-centred and linear expressions of sound passing through time, we are also able to listen for space – the sputter of an engine up close in the humid outdoors, the sense of cavernous space as voices echo in what must be a giant construction arena; the sound of unknown, mysterious objects being shuffled around in a dry, enclosed indoor space.

In his own words: Amrakajona Zakir Hossain Khokan is a community organizer and change maker. He and a migrant local volunteer team have been raising awareness, promoting diversity, and empowering migrant communities through literature, reading, photography, film, blood donation drives, book fairs, panel discussions, human libraries, stage poetry plays, art exhibitions, book publishing, and other art activities from Migrant Writers of Singapore or Bangladesh Book Fair; Singapore, to One Bag One Book and Migrant Worker Photography Festival. Zakir is an award-winning poet and a quality control project coordinator in the construction sector.

Q: Any sounds that remind you of your home?

A: The sound of my son calling be Abby

Q: Sounds you will remember forever?

A: The voice of my father. How he called my name - Khokan.