Long-term learning in youth education

Strategy Games in Language Teaching

How do you motivate youngsters to stay on the ball when learning a foreign language? How can schools contribute to personality development? Experience shows that strategy games can help achieve both of these goals, as well as giving kids a better understanding of democratic decision-making processes.

By Dr Katharina L. Ochse

“You have to be able to understand other people’s ideas, to really listen to others,” explains Anna Helēna Markova (17), a high school student at the Englisches Gymnasium in Riga. “Decisions have to be thoroughly analysed and discussed before they’re reached,” she adds, summing up her impressions of the Climate-Neutral City online strategy game contest held by the Goethe-Institut at 15 schools in Central and Eastern Europe and in Russia.

Strategy games are a means of experiential learning, i.e. learning by addressing (and solving) real-life problems. The learners play active roles. Experiential learning is considered particularly effective in the long term. In strategy and role-playing games, young people gain experience and develop skills that aren’t usually involved in regular classes, but are very important for growing up, e.g. developing and defending one’s own opinions, positions and interests, dealing constructively with conflict, debating issues, developing negotiating skills, putting oneself in others’ shoes and making decisions. In a strategy game, young people experience how difficult and yet important it is to take different interests into consideration and work out compromises in a democratic society.

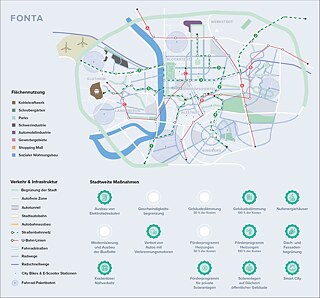

A strategy game involves a real or made-up problem that concerns various stakeholders with more or less conflicting or divergent interests. For example: How can a city reduce its carbon footprint, i.e. its CO2 emissions? Or: How do you set up a school café? Or: How do you prevent littering in public parks?

The players take on the roles of stakeholders and view the problem or challenge from various angles. They propose and discuss potential solutions. The outcome is not predetermined. So they can consider various solutions in a round-table discussion with a view to arriving at a unanimously acceptable result. They don’t merely come to grips with the subject-matter and talk about it and the challenges involved: they experience and participate in problem-solving and democratic decision-making processes.

You need at least ten people for a strategy game to develop various roles with conflicting interests and generate a lively debate.

Strategy games are suitable for young people aged 14 and up.

Strategy games’ potential language-learning benefits

Many young people find it frustrating to be unable to express themselves in a foreign language on a level corresponding to their age and general knowledge. So teachers may find it particularly challenging to get their pupils to actively take part in this experience. Strategy games are an effective method for getting students to improve their German – even if they don’t play the game (entirely) in German.

B2-level proficiency is a minimum prerequisite for a real discussion in a foreign language. Does that mean strategy games are not suitable for German learners at lower levels of proficiency? On the contrary, they can play strategy games in their native language and work some foreign language elements into the discussion, e.g. by presenting the results of the discussion in German. Even A2-level proficiency in German is sufficient for this purpose.

If you have your pupils record their presentation in German on video, as in the Climate-Neutral City strategy game contest, that will give them an opportunity to develop their media skills and creativity as well. The resulting “product” will serve as a record of the game’s results and can be visibly presented on your school’s homepage and in social media.

2. The form of implementation: online or analogue?

In terms of didactic concept, there’s no fundamental difference between online and analog strategy games. Online games can be played entirely online (even from home) or in “hybrid” form, e.g. on digital devices at school. They require appropriate equipment and a stable Internet connection. Online strategy games can enhance learners’ media competence. Studies have shown that participants in analog strategy games find the direct personal interaction involved particularly motivating. Furthermore, participants in analog or hybrid online strategy games can express themselves more spontaneously, which in turn tends to yield livelier and more emotional discussions.

Actually, any problem whose long-term solution requires the involvement of actors with divergent interests is a suitable topic for a strategy game. So there’s a great variety of possible topics for strategy game scenarios. The topic need not be closely related to the learners’ immediate everyday world, so this isn’t a decisive consideration. On the contrary, your pupils may find very appealing an opportunity to slip into a role and immerse themselves in a world that is not directly related to their everyday reality and to develop within that world. Naturally, in order to get pupils to participate, it’s important for them to be able to relate to the topic, so it’s a good idea to involve them in the process of choosing a topic – which is also a way of preparing them for the participatory processes they’ll be exercising in the strategy game itself.

4. The implementation period

Like the range of potential topics, the length of a strategy game can vary considerably too. Some take two hours, others can run for a whole week. Whether a strategy game is going on for “too long” depends on the desired outcome and how important you feel that outcome is.

If you choose a topic of interest for the whole school and conduct the strategy game largely in the local language, it can be quite suitable for interdisciplinary cooperation, e.g. as part of a project week.

Effectiveness of strategy games

“I realized I like being in power,” said one pupil when asked what he’d learnt in the Climate-Neutral City strategy game. This answer is revealing in several respects. Apparently, the actual topic of the strategy game wasn’t all that decisive for him. Instead, he associates taking part in the game with a cognitive insight about himself as well as positive emotional self-awareness. The delight in having “power” in the game may be an indirect reaction to the reality of schoolkids, who have very little autonomy in their everyday lives. This young man’s remark goes to show how important it is to talk to participants after the game about their experiences and impressions. Power, the abuse of power, and responsibility are important issues in every society. Democracy stands or falls by the responsible use of power.89 percent of the participating pupils would take part in another strategy game. 77 percent could imagine improving their knowledge of German so they would be able to take part in a strategy game in German. Therefore the strategy game had a very positive impact on their motivation to learn this language.

Almost 90 percent said they could imagine taking part in a real-life round-table debate, in other words getting involved in socio-political issues. In this age of dwindling voter turnout and waning trust in the system of representative democracy, this feedback from high school students is a glimmer of hope for the future.