Opening: Goethe Centre Baku

Amidst Chapels and Mosques

In December of last year, two new Goethe Centres opened in Yerevan and Baku that see themselves as mediators between Europe and Asia. The Goethe Centre in Baku was now officially opened in the presence of Johannes Ebert, secretary-general of the Goethe-Institut. He emphasised the bridging function of Azerbaijan as one of the most open among the predominantly Islamic states in the region.

The Silk Road, which was already the subject of several events at Baku’s Goethe Centre, is the common thread of the cultural programme in the Kapellhaus of the neighbouring Lutheran church and the seat of the Goethe base. It is a road of history and lore, where not only wares, but also cultural goods, worldviews, religions, traditions and customs were made known, transmitted and exchanged among the peoples.

Mischa Kuball, Johannes Ebert and Alfons Hug at the opening

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Mischa Kuball, Johannes Ebert and Alfons Hug at the opening

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Quiet yet urgent gestures

The Caucasus has been a troubled world region for millennia. It is tempting to want to give well-intentioned advice in this conflicting situation, but Alfons Hug, director of the Goethe Centre in Baku, emphasises the miraculous effect of quiet yet urgent gestures. For the opening exhibitions he sent the Egyptian artist Youssef Limoud, who lives in Basel and Cairo, through the streets of Baku for three days to collect random materials for an installation, and he commissioned the German light artist Mischa Kuball to design a colourful, highly symbolic light sculpture for the Shah’s Mosque of the Palace of the Shirvanshahs.Although Kuball has already shown his work in churches of various denominations, he reported that any attempts to present his light art in a mosque had failed. Kuball reflected a groundbreaking discovery by the Italian polymath, philosopher, mathematician and astronomer Galileo Galilei, who for the first time observed the sunspots and interpreted them not as an optical phenomenon but as structures on the sun’s surface.

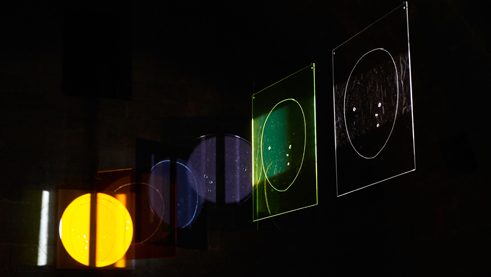

Light installation by Mischa Kuball

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Light installation by Mischa Kuball

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Science and faith

In Kuball’s light installation “Five Suns / after Galilei,” five differently coloured panes, upon which he engraved the sunspots as seen by Galilei, rotate in stoic proportions with and against each other, while the beam of a projector lamp conjures colour patterns in ever new combinations on the wall of the now inactive fifteenth century women’s mosque. Kuball sees his work not only as a reminder of the old dispute between reason and dogma, science and faith, which Galileo faced in his arguments with the Catholic Church. The work is also a tribute to the tolerance practised in Azerbaijan and the multicultural wealth of the country in the Caucasus.Youssef Limoud’s work traverses a completely different path. In the three days in which he roamed the streets of Baku, he collected a wealth of found objects, pipes, rough bricks, wire baskets, metal pins, gratings, bars, metal discs, and charred laths. He quickly built miniature city settlements in the Kapellhaus that have one thing in common: they are city ruins with inherent signs of decay and decline to which Limoud’s artistic hand lends an incomparable poetic magic.

Exhibition by Youssef Limoud

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Exhibition by Youssef Limoud

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Symbols of transition and transformation

Limoud’s ruined cities end up in the rubbish after the end of the exhibition. He built his biggest ruined city two years ago at the Dakar Biennial and received the first prize for it. He sees his elaborate, temporary creations as symbols of transition and transformation: Nothing is permanent, eventually even the most fantastic work of art or building, in the figurative sense even the most powerful system of government or even some social ideals, fall to ruin or disappear completely. Limoud inscribed his installation with the ambiguous Arabic word “maqam,” which generally refers to a place ‘on which something is erected,’ which also denotes a certain scale in Arab, Turkish and Persian art music. Opening ceremony of the Goethe-Zentrum Baku

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Music also played an important role in the opening days of the Goethe Centre in Baku. For one, the Unsound Festival of electronic and experimental music took place at the same time in the Lutheran Church. In particular, however, for the opening ceremony Azerbaijani singers and musicians worked together with a jazz pianist – much in the spirit of Goethe’s “West-Eastern Divan” – to combine traditional Mugham music with modern “Western” sound perceptions in a “harmonic” way. The universality of music, which is perhaps best suited among the arts to bridge gaps or even abysses in human interaction, was also heard in the concert by the female vocal ensemble Sjaella from Leipzig, which performed songs from almost every era of European music.

Opening ceremony of the Goethe-Zentrum Baku

| Photo: Adil Yusifov

Music also played an important role in the opening days of the Goethe Centre in Baku. For one, the Unsound Festival of electronic and experimental music took place at the same time in the Lutheran Church. In particular, however, for the opening ceremony Azerbaijani singers and musicians worked together with a jazz pianist – much in the spirit of Goethe’s “West-Eastern Divan” – to combine traditional Mugham music with modern “Western” sound perceptions in a “harmonic” way. The universality of music, which is perhaps best suited among the arts to bridge gaps or even abysses in human interaction, was also heard in the concert by the female vocal ensemble Sjaella from Leipzig, which performed songs from almost every era of European music.