Bicultural Urbanite Brianna

How I got home: Berliners stuck abroad during the crisis

After the coronavirus went global, governments around the world launched repatriation efforts to bring back thousands of citizens stranded abroad. Two friends of mine were among those caught out when the virus closed borders and shut down public life. They both registered with the German Federal Foreign Office in an attempt to be rescued.

By Brianna Summers

When Nik flew to New York City, he didn’t realise it would quickly become the epicentre of the US coronavirus outbreak. Two days after he arrived, America closed its borders and his return flight was cancelled. Initially, he was delighted: he’d made it into the country to visit his girlfriend and now he had a legitimate excuse to stay longer than he’d planned.

Nik poses in a deserted Washington Square Park with 5th Avenue in the background

| © Nik Bielinski

It quickly became apparent that Nik didn’t need a good excuse for his boss back in Berlin. The day after his flight was scratched, he read on WhatsApp that the hostel he manages had closed for the foreseeable future and his job was on the line. For Nik, the drama of getting stranded abroad and potentially catching the coronavirus paled in comparison with the prospect of being sacked overnight after years of service. “This was my biggest issue. Coming back, not knowing if I had a job or not,” he says.

Nik poses in a deserted Washington Square Park with 5th Avenue in the background

| © Nik Bielinski

It quickly became apparent that Nik didn’t need a good excuse for his boss back in Berlin. The day after his flight was scratched, he read on WhatsApp that the hostel he manages had closed for the foreseeable future and his job was on the line. For Nik, the drama of getting stranded abroad and potentially catching the coronavirus paled in comparison with the prospect of being sacked overnight after years of service. “This was my biggest issue. Coming back, not knowing if I had a job or not,” he says.

Your registration has been received

As Manhattan became a ghost town populated exclusively with “homeless people and millionaires”, Nik wrangled with Lufthansa. After his flight had been repeatedly rebooked and cancelled, he added his name to the Electronic Register of Germans Abroad on the German Federal Foreign Office website. He received an automated email response and nothing else. The service was completely overwhelmed.

Nik had been marooned for two weeks when he sent me this cryptic text message: “I have been awake for 24 hours. And I had a beer breakfast.” Lufthansa had come up with the goods: He was at the airport and despite his flight being overbooked, he’d managed to land a seat.

Meanwhile, in the southern hemisphere, my friend Ulli was backpacking through Peru when “a bombshell was dropped in paradise”. She had been blissfully unaware of the pandemic media churn until she happened to catch the president’s televised announcement on 15 March: Peru was closing its borders to Europe the following day, for a minimum of one month.

No way back

Panic spread at different speeds throughout the hostel: “Some people were very chilled-looking, like, suspiciously so. The big French faction immediately kicked back, bought two bottles of whiskey and several bottles of wine, popped them open, with their Gauloises…while I, like a panicked chicken, fluttered all around them trying to get my way out of the country,” she recalls. Ulli furiously googled flights to Berlin and bought an overpriced ticket that was soon cancelled as other borders closed around the world.

Ulli in paradise, before she realised she was trapped.

| © Ulrike Keil

Ulli in paradise, before she realised she was trapped.

| © Ulrike Keil

The next bombshell dropped the following day. The entire country was going into a 14-day military-style lockdown. Like many tourists she scrambled to Lima, later realising it wasn’t the greatest move. “Everything got knotted up in Lima. The military had their foot on the airport and they did not allow shit from there,” she recalls.

The relief of checking in to a swish hostel in the capital was soon quashed when police arrived to explain the finer points of the lockdown: guests were only allowed to leave their rooms to buy food and the communal kitchen was closed. The prospect of two weeks lying in a dormitory bunk bed eating readymade cold food was too horrible to bear.

Clusters of anxious travellers quickly formed and Ulli latched onto a “promising group of young, energetic people with a laptop” who became her AirBnB flatmates. The five Europeans spent their time in the Peruvian Big Brother house making videocalls, cooking, watching Netflix and filling out countless repatriation registration forms. Outside the flat, armed police and military personnel patrolled the streets.

"Filling out forms became my new hobby"

The numerous, hastily prepared repatriation websites kept crashing and were eventually consolidated into a single portal called Rueckholprogramm.de. The German Federal Foreign Office also sent out an “incredibly transparent and honest” newsletter every day, even when there were no new developments. “That I really appreciated, because it was really relieving, psychologically,” she says.

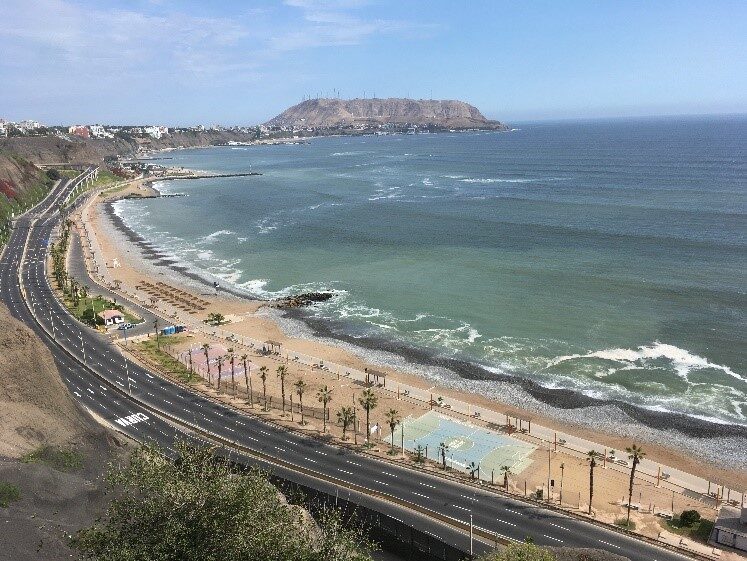

Lima in lockdown: Not a soul in sight

| © Ulrike Keil

The flat was empty when Ulli finally won her “lottery ticket for the golden repatriation flight”. She took a taxi to Lima’s military airport, clutching a transportation permission slip and other official paperwork issued by the German government that allowed her to move freely and catch her flight.

Lima in lockdown: Not a soul in sight

| © Ulrike Keil

The flat was empty when Ulli finally won her “lottery ticket for the golden repatriation flight”. She took a taxi to Lima’s military airport, clutching a transportation permission slip and other official paperwork issued by the German government that allowed her to move freely and catch her flight.“The [German] government was so thorough, they were the only ones that bothered about all the paperwork for getting back…none of the other nationalities had it,” she says. After passing through a makeshift departure area on the tarmac manned by soldiers and sniffer dogs, the stranded travellers boarded and the plane took off straight away, “zack zack, German-style!”

Given the complexity and cost of the pandemic rescue operation, it’s quite astonishing what the German government managed to organise, fund and execute at short notice. Families and people with pre-existing medical conditions were prioritised, deals were struck with airlines and foreign authorities, and so far over 240,000 German citizens have been brought home. Let’s hope they won’t have to do it again for at least another hundred years.