Brisbane International Film Festival

Blue Velvet Revisited: In dreams, I walk with you

Deployed for decades to describe the dreamlike quality of David Lynch’s work, ‘Lynchian’ is now officially a word. Just this month, it was added to the Oxford English Dictionary along with more than 100 other film-related terms and phrases, such as Kubrickian, Spielbergian and Tarantinoesque. As proves the case with each director-derived expression, Lynchian’s inclusion not only immortalises the filmmaker’s distinctive style, but also recognises the fact that it no other term can do it justice. When the surreal blends with the mundane and everyday, especially through visual storytelling cloaked in an air of mystery, it’s the explanation that rolls off the tongue. Now, it’s the explanation that sits in the dictionary as well.

It’s easy to understand why with Lynch in particular; across a distinctive and inimitable oeuvre that commenced with his 1977 debut Eraserhead and includes three seasons of Twin Peaks made across nearly three decades, his approach to filmmaking has marched to the beat of his own drum. ‘Lynchian’ isn’t just a descriptor for the director’s own output, however, but for anything that attempts the near-impossible feat of mimicking his sensibilities. It shouldn’t come as a surprise that Blue Velvet Revisited strives to earn this label, although what is least expected is how well it fits the mould. Subtitled ‘a meditation on a movie’, this documentary snapshot by German filmmaker Peter Braatz compiles grainy behind-the-scenes footage and monochrome photographs — the former shot by Braatz on Super-8 — to pay tribute to Lynch’s Blue Velvet in a manner that Lynch himself would likely approve of.

Inhabiting, rather than dissecting

The backstory behind Blue Velvet Revisited is integral to its effectiveness — and, crucially, to the feeling that it radiates. How did an aspiring German director find himself not only on the North Carolina set of one of Lynch’s iconic movies, but recording what happened when the feature’s own cameras weren’t rolling? By asking, simply enough. As an eager and enthusiastic aspiring filmmaker, Braatz wrote to Lynch in 1984. He received a typed response: “Dear Peter, I am interested. Sincerely, David. K. Lynch”. Later, Lynch sent a follow-up: “We are making an extremely low-budget film, Peter, so bring a lot of money and help us out”.It’s a turn of events that could easily have taken place in one of Lynch’s own features, sparked by a young man curious about a subject, drawn to investigate further and soon immersed in its most wonderful and strange realm. While Braatz isn’t Blue Velvet’s Jeffrey Beaumont (Kyle MacLachlan) or Twin Peaks’ Agent Dale Cooper (also MacLachlan), he’s following a similar path. Drawing a parallel himself, it’s not by accident that Braatz begins Blue Velvet Revisited as Lynch begins Blue Velvet. Each opens with a close-up of a severed ear lying on a suburban lawn, signifying both the subversion of an idyll and the entrance into atypical territory.

As woven into a collage-like effort three decades later, Braatz’s film follows the thrust of Lynch’s movie through the materials captured at the time, sorting through more than six hours of Super-8 footage and over 1000 photographs. But Braatz’s concept of revisiting Blue Velvet doesn’t involve dissecting it or Lynch, but rather just inhabiting their world. Set to a soundtrack by Tuxedomoon, John Foxx and Cult With No Name, Blue Velvet Revisited lets much of its observational visuals play out with no form of explanation, other than occasional inter-titles on screen that often repeat lines of Blue Velvet’s dialogue. Over the top, it sometimes layers audio from the film, as well as soundbites from interviews with Lynch, and stars Dennis Hopper, Jack Nance, Isabella Rossellini and Brad Dourif, and others.

Lynch unguarded

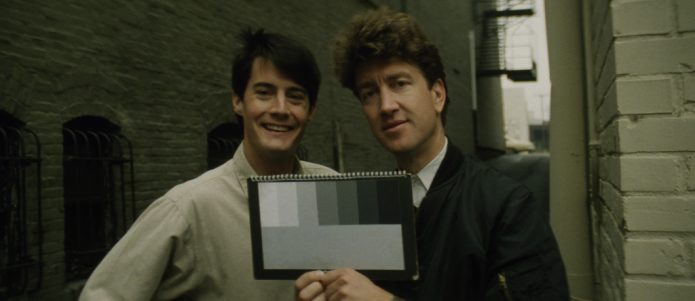

Far from disappointing in its lack of analysis, the effect is — as befitting the term that Lynch has given rise to — both ethereal and routine. Or to place it in the world of the movie it’s focused on, it recalls Blue Velvet’s memorable Roy Orbison-soundtracked musical scene: “in dreams, I walk with you”. Blue Velvet Revisited showcases the usually ordinary experience of hanging around a film set, yet wholly captures Lynch’s brand of movie magic. Looking at snaps of film locations, cast members bantering before ‘action’ is called and Lynch taping a sign onto a van’s panel has rarely been more alluring, albeit more for fans of both Lynch and Blue Velvet more than others. And while it threatens to stretch the boundaries of its structure and style with its pacing at points, Blue Velvet Revisited also proves revelatory, specifically where Lynch and his creative process is concerned.Viewers can tell much about Lynch, and the way that he tackles filmmaking, simply by watching him at work. His passion and precision, his instinctive knack for mood and tone, and his devotion to his vision all come through in his unguarded moments. Indeed, appearing almost boyish with his light and fluffy brown hair, the then 39-year-old is as unguarded as he’s ever been in a documentary — and that’s especially true when he’s talking. Many films have been dedicated to Lynch, such as 2016’s David Lynch: The Art Life, while he has also shot his own, including a short, Lamp, about just making a lamp. But Braatz gets Lynch chatting about Blue Velvet, the limits of technology, and his general style, inspiration and fascinations with visible passion and ease that he seldom displays when he’s being overtly scrutinised. Delivered in fits and spurts based on several off-the-cuff tapings, the discussion ranges well beyond the level of detail Lynch gives in more recent interviews, for example.

Perhaps that’s a matter of timing, with Lynch’s career still in its nascent phase in the mid-1980s. Perhaps making such enigmatic, complex, polarising and masterful fare as Blue Velvet stripped him of his willingness to share his thoughts, with the director frequently making plain that he’d prefer his work to speak for itself sans explanation. Or, perhaps his candour with Braatz is a gift to someone that’s keen to follow in Lynch’s footsteps, and clearly in his thrall — and now, courtesy of a rich and poetic ode of a feature that captures the Lynchian atmosphere above all else, it’s Braatz’s gift to the world.