In conversation with Gesche Ipsen

Translation can adjust the balance of power

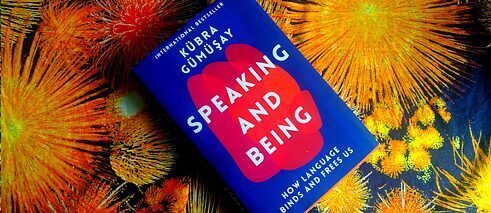

In “Speaking and Being” Kübra Gümüşay explores the question of how language shapes our thinking and determines power relations in our society. The book has now been published in English translation. We talked to the translator, Gesche Ipsen, about her work on the book and the linguistic power of translation.

By Stephanie Hesse

Kübra Gümüşay begins her book with a very personal insight into her relationship with language. She herself speaks three and, as she says, feels four languages: Turkish, German, English and Arabic. Many terms, phenomena, situations or feelings that exist in one language cannot be translated exactly into another. How did you feel about the English translation of “Speaking and Being”?

I actually can’t think of anything that caused too much of a headache. German and English are fairly close in terms of cultural background, I think, which means that both personally and as a translator I don’t usually find it difficult to move ideas and concepts from one into the other. It's more the grammatical and rhetorical differences that take some time to iron out: for instance, German is an inflected and gendered language, while English isn’t, and German is centred much more around nouns than English, which relies more on verbs and qualifiers.

The author illustrates her statements with an incredible number of stories of incidents, with observations or conversations. Is there a story in the book that particularly stuck in your mind?

Gümüşay’s account of the animosity she experienced as a thirteen-year-old(!) after 9/11, and the pressure put on her by others to speak about complex matters with the expertise of some kind of veteran Reuters journalist is incredibly moving. As she says, at the same time ‘we receive no recognition for allowing ourselves to be scrutinised and interrogated, and our attitudes to be tested. Our knowledge is worthless knowledge.’

She also reminds us that there are so many different ways of looking at the world: early on in the book, she describes how the linguist and erstwhile Christian missionary Daniel Everett’s encounter with the Pirahãs – an Amazonian tribe with a very different approach to knowledge and faith – resulted in his becoming an atheist; and then there are the Thaayorre in Australia, for whom compass points play a much bigger role than for us, and who, for instance, think of time as passing from East to West. If we taught schoolchildren everywhere more about such different ways of conceptualising the world, humanity might be in a far better place. As Gümüşay asks, why do school curricula only include books by authors who write in a country’s official language(s)? Perhaps it’s a leftover from the days when nation states first came into being, or first became aware of themselves as nation states, and understandably wanted to create an identity narrative. But aren’t some countries – like Germany, the UK, the US – long past that point? Shouldn’t we include more translated literature right from the off, and certainly no later than the age of sixteen or so?

Kübra Gümüşay addresses many references from German society and contemporary history. The English version of “Sprache und Sein” differs from these references in some places and describes alternative phenomena from the English-speaking countries. What is it about these variations?

I didn’t make these changes myself. Rather, Gümüşay worked with Louisa Dunnigan, the commissioning editor at Profile, and her team to find the new material. The reason Sprache und Sein warranted publication in English in the first place is that it’s both very personal and very international. Gümüşay’s experiences are rooted in Germany, yes, and these remain unchanged in the English-language version, but the implications of her experience go beyond Germany. In the original, she discusses several international events (the 2019 Christchurch murders, Brexit, etc.) and draws on many English-language sources, so it was really a matter of supplementing what was already there.

A perfect example of this is the story of the barrister Alexandra Wilson, which Gümüşay recounts in the Speaking Freely chapter. In the original edition, Gümüşay describes how Gloria Boateng, a German teacher and educational activist, was ‘mistaken’ for a cleaner by a colleague at the university where she worked. I’m sure everyone in the UK has heard about Wilson’s experience one morning in 2020, when she arrived in court and was mistaken for a defendant no fewer than four times, as she made her way from the entrance to the courtroom. Her story immediately sprang to mind when I read Boateng’s, and Gümüşay agreed that it made sense to substitute it. Her point in telling Boateng’s story wasn’t to say, ‘Look how bad things are in Germany’, but precisely the opposite: that, as Gümüşay writes, ‘this kind of dehumanisation is systematic’ – which is why the additional material in the English edition comes from the US, Australia and New Zealand, as well as the UK.

The book questions the power of language in a political and social context. In doing so, Kübra Gümüşay repeatedly emphasises the dichotomy of language. The subtitle of the English translation is very fitting: "How language binds and frees us". How would you answer this question from a translator's point of view?

When you translate a text, you’re literally bound by the original language. After all, it’s the tool that the author employs to communicate with you, and you can only work with what you’re given. But once you’ve read the words in question, the next thing you do is listen to them. What exactly do they want to express, and how are they expressing it? It’s like a verbal fencing bout: there’s a flurry of parry-and-riposte, and eventually you land a hit, and what was once unintelligible to the posited reader is now intelligible. Yet the very act of translating a book from one language to another can also contribute to a general adjustment of the balance of power. Someone’s voice can now be heard beyond the more or less arbitrary borders of the territory in which they happen to live. More than that: through the translation, the reader encounters the mind of someone from another country and/or culture with a very specific story to tell, and is allowed a glimpse of the granular reality behind national and cultural stereotypes.

Speaking of the power of language: What do you think is the role of translators in this context?

Translators are vassalled autocrats. We bow before the words we translate, and before the posited reader for whose benefit we are translating them, while knowing full well that we alone (barring of course our editors) have the last word. This doesn’t make us hypocrites, though – just painfully aware of the old adage that with great power comes great responsibility. A translator can make a great author sound pedestrian, and vice versa, and various factors determine whether or not you end up doing justice to the original. To choose the right formulation, you not only need to consider the form and content of the text in all its subtlety (or otherwise), but also apprehend the register: who (and this ‘who’ includes the narrator) is saying what to whom, and why? And how much time and energy can you, or are you willing to, expend on all this? How well can you write in the language you’re translating into? It’s hard work, and you need to be disciplined, focused, imaginative, creative, and above all honest – not least with yourself.