40 Jahre Goethe-Institut Neuseeland

Sarah Laing

It was 1989, or perhaps it was 1990, and I was a 6th or 7th former from Palmerston North. My classmate had visited Germany recently and she brought home a chunk of the Berlin wall. We passed it around, feeling its weight and grittiness, trying to imagine what the shard of graffiti might spell, and what the absence of the wall might mean. My classmate was better at German than me – she had the kind of mind that filed vocabulary and grammar meticulously – but I sounded more German. German tinged with the Dutch accent of my teacher, Frau Schomaker.

Frau Schomaker was an exacting and charismatic teacher. She taught us about the dative, accusative and nominative. We had to wear red bow ties with our uniform, and whilst some teachers would let us get away with keeping them tucked under our polyester royal blue V-necked jerseys, she would insist upon us revealing them. “Ach, girls, you are like lactating mothers flopping out your breasts! Why don’t you wear them at your neck like you are supposed to?” At our necks they choked us. Only the most goody-good of girls wore their bowties at the neck.

There was a reason why I sounded the most convincingly German. This was because I had lived in Germany for 18 months in 1979 to 1980, first in Munich and then in Göttingen. My father had been awarded a fellowship at the Max Planck institute. I remember my first months at the big Munich school, unable to speak the language, crying at the fringes of the concrete playground, unable to write in the Germanic script even though I had learnt to print in New Zealand, in the remedial class with the Turkish Gastarbeiter children. My grandmother had come along to help my mother with my baby brother and 3-year-old sister and when she took us down to the playground she told me to tell the other kids “Icky spricky kein Dutch”.

By the end of our time in Germany I was pretty fluent and owned a left-handed Pelikan fountain pen with which I could write in cursive. I had neighbourhood friends – half-Haitian, half-German sisters called Miriam and Katrina – and we would roam the countryside around our village, Nikolausberg, stealing apple turnips and cherries from the local farms and climbing into the ruins of old castles. They made me braver than I naturally was. The orchardist who caught us stealing his cherries was livid.

Upon our return, my mother enrolled in German papers at Massey and tried to speak German to me in the streets of Palmerston North. She insisted that I call her Mutti, but I was too embarrassed. I wanted to call her mum. She refused that moniker. We settled on Robyn. She filled the house with German friends and Germanophiles and we would go to Goethe society barbecues and throw potluck dinners of our own.

There was a bunch of other teenagers sitting in the Goethe-Institut reception. They too had been vetted by their local university German department, and were chosen as contendors. We gauged each other but didn’t chat. I wondered if they had any unfair advantages – were their parents German? Had they lived there like I had? Or were they just uncannily good at picking up languages? We were called into the examining room one by one. I chewed my nails as I waited and sang Blau blau blau sind alle meine Kleider in my head.

Two women smiled brightly at me. They had interesting-looking glasses and the kind of clothes that came from Europe. I don’t remember much of the conversation apart from the fact that I knew I had made mistakes, and that my nervousness made me taciturn. Did we have to also do a written test? Maybe. Did they tell us who had secured the 3-month scholarship to study in Germany on the same day? I suspect not, as my next memory is of us all walking to the Mexican Cantina in Edward Street. If I had found out I had not won, I probably would’ve cried my way down Victoria Street.

The Mexican cantina seemed like a wondrous place. Palmerston North wasn’t known for its exotic restaurants and there was nothing like that there. The place was brick and festooned with coloured flags and little skeletons. There were sombreros everywhere. Upon arrival, we were presented with bowls of nacho chips and salsa. We spoke German and ate enchiladas and I felt an inkling of what my like might be like when I left my home town.

No, I didn’t get the scholarship. I wanted it badly – I felt homesick for the country where I’d once lived – but I didn’t really deserve it. I moved to Wellington the following year, and I took my new hostel friends to the Mexican Cantina. This place is great, they agreed. This is really fun!

I went to the same restaurant a few weeks ago. It’s now Japanese and serves tempura and sashimi. It has the same brick walls and the same cosy vibe. It’s down an alleyway that feels surprisingly un-Wellington. I no longer speak much German although I like to imagine that it is a cicada nymph in the soil of my mind, and that in the right conditions – a year in Berlin, perhaps – it would grow wings, flex its tymbals and sing.

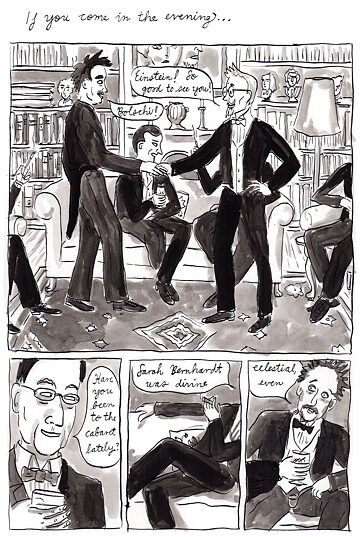

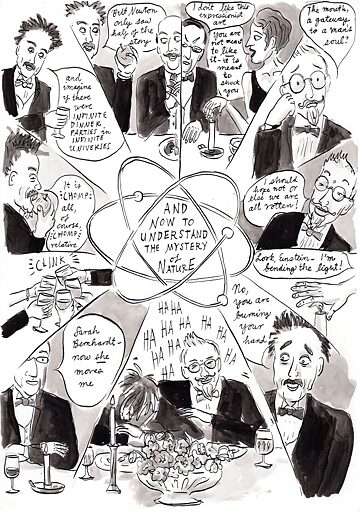

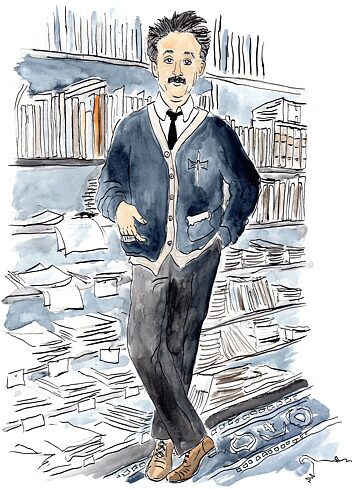

As an adult I have had the luck of working with the Goethe-Institut. I turned Albert Einstein’s poems into an 24-page comic book. Did you know that Einstein wrote poetry? He wrote doggerel about his unpleasant dental experiences and to thank his friends for inviting him for dinner. It wasn’t all quantum physics. He, like all of us, contained multitudes. He, like me, was thankful.