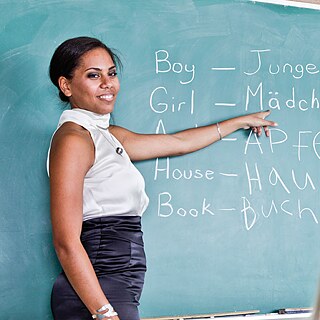

Teaching German

The Goethe-Institut is the world's leading provider of professional development for German teachers. We provide you with up-to-date material and interactive services.

Experienced Teaching ensures your success

Learn German from the market leader. We offer German language courses and exams in over 90 countries.

The Goethe-Institut is the world's leading provider of professional development for German teachers. We provide you with up-to-date material and interactive services.