Look at the process, not the outcome

What is Memory Culture?

The wide-spread protests that toppled statues symbolizing white supremacy, racism, and colonial violence in the United States and elsewhere suggest that a deeper reckoning about the past may have finally begun. In this context, observers have pointed to Germany as a model for the successful confrontation with history. However, rather than looking at the outcome of Germany’s reckoning with its multi-layered past, it is much more instructive to understand the process that led to this outcome.

By Jenny Wüstenberg

The American philosopher Susan Neiman calls on us to “learn from the Germans,” while Bryan Stevenson, the man behind the National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, AL, has said repeatedly that Germany’s landscape of memory was a key inspiration for his project. These arguments make the case that it is possible – and necessary – for democratic societies to take responsibility for legacies of the past in the present. Germany does indeed have an unparalleled infrastructure of memorials and educational institutions that “work through the past”.

Tireless work of activists

However, simply seeing Germany’s memorials as models for our current “statue problem” is misguided. Rather than looking at the outcome of Germany’s reckoning with its multi-layered past, it is much more instructive to understand the process that led to this outcome. Indeed, for decades, German society and its leaders were as unwilling to face up to their crimes as the powerful in the U.S. What brought change and had made the German approach to commemoration into one that is seen by many as a model to be emulated, was not a sudden epiphany, but the tireless work of activists – Holocaust survivors, initiatives for reconciliation, and citizens’ groups. This, indeed, is a lesson for us all: we need to allow for civil society to be heard as we debate whether to take down these statues – and what we should set in stone in their stead.The Holocaust Memorial in Berlin as an antithesis to a more decentralized memory landscape

The Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe sits at the heart of Berlin, next to the Brandenburg Gate, and is often cited as the epitome of the extent to which Germans have embraced the need to take responsibility for the past. And indeed, quick comparisons indicate the extraordinary nature of this approach: Can you imagine a memorial recalling the victims of slavery next to the Washington monument on the National Mall? What would it take to place a monumental site symbolizing the crimes committed in the name of the British Empire on Trafalgar Square? How much would Australian political discourse have to shift for there to be a commemoration of the children stolen from Aboriginal families next to the Sydney Opera House? In each of these cases, such memorials would be phenomenal acknowledgements that the past must be addressed, suggesting a willingness to tackle continuing legacies of colonialism and racism in the present.However, the Berlin Holocaust memorial is not the best example of why it’s worth taking a closer look at Germany’s history of commemoration. Though it was initiated by a small Berlin-based group lead by publicist Lea Rosh and the subject of many years of public debate, it was ultimately at least partially made possible by elite political bargaining. In fact, many of those who were actively working for Holocaust memory at the time were opposed to placing a large monumental structure in a central location, fearing that this might foster a feeling among Germans that they had done their bit to remember and could now legitimately move on. What makes Germany’s approach to the past distinctive is not the presence of a large memorial but rather their decentralized memory landscape – the assemblage of thousands of markers, plaques, small exhibitions, and large memorial museums – that makes up the topography of terror, showing where the daily realities of a genocidal regime happened.

A large memorial in the capital is a place you can tick off on a touristic visit. A “landscape” is something that is encountered in everyday life by residents and guests alike and that cumulatively brings home the point that the Holocaust was possible because so many people and places actively and passively participated. A memorial in the capital can be mandated from above by the federal parliament – a feat that is of course an important signal in itself. But a landscape of memory is only possible because thousands of individuals and civic initiatives worked locally to research and mark history. This process is where the United States and other societies could learn from Germany – not because they should arrive at the same kind of outcomes in terms of commemoration – but because “working through the past” requires open-ended public debates that give pride of place to civil society voices.

From commemorating “German suffering” to commemorating the Holocaust

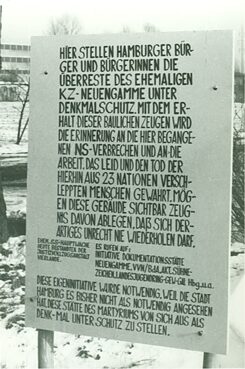

Protest sign erected at the site of the concentration camp at Neuengamme, 28 January 1984

| Photo: KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme, F 1986-7113

After the Second World War ended in 1945 and once the two German states were founded in 1949, there were, in fact, immediate efforts to commemorate the war experience. Thousands of monuments were built in the 1940s and 1950s – so there wasn’t exactly silence about the past. However, in West Germany, almost all of them recalled, not the Holocaust, but experiences of “German suffering” – the expulsion and flight of ethnic Germans from East-Central Europe, the aerial bombardment of cities, the return of prisoners of war, the repression through Stalinist authorities in the Eastern zone of occupation. In East Germany, while there were similar efforts, public space was quickly seized by the communist regime and autonomous activity quickly became extremely risky – even when commemorative activity seemed to be compatible with the official line of honouring the communist resistance against Nazism.

Protest sign erected at the site of the concentration camp at Neuengamme, 28 January 1984

| Photo: KZ-Gedenkstätte Neuengamme, F 1986-7113

After the Second World War ended in 1945 and once the two German states were founded in 1949, there were, in fact, immediate efforts to commemorate the war experience. Thousands of monuments were built in the 1940s and 1950s – so there wasn’t exactly silence about the past. However, in West Germany, almost all of them recalled, not the Holocaust, but experiences of “German suffering” – the expulsion and flight of ethnic Germans from East-Central Europe, the aerial bombardment of cities, the return of prisoners of war, the repression through Stalinist authorities in the Eastern zone of occupation. In East Germany, while there were similar efforts, public space was quickly seized by the communist regime and autonomous activity quickly became extremely risky – even when commemorative activity seemed to be compatible with the official line of honouring the communist resistance against Nazism.In both East and West, Holocaust survivors and their supporters were almost alone in demanding a public acknowledgement of responsibility through commemoration. Groups such as the Vereinigung der Verfolgten des Naziregimes/Bund der Antifaschisten (VVN-BdA) worked tirelessly, not only to preserve and mark sites of Nazi terror, but also to conduct historical research and support victims. Even some of the early prominent sites of commemoration, such as the Bergen Belsen memorial and the memorial at the Bendlerblock in Berlin (where the conspirators of the 1944 plot against Hitler had been active) were the outcome efforts by survivors and relatives of the conspirators (for example through the “Hilfswerk 20. Juli 1944”). Only gradually did non-victims become involved in memory work. The oldest and most important initiative is Aktion Sühnezeichen/Friedensdienste (ASF), a Christian group that has been working for atonement and reconciliation in East and West since 1958. But most of the thousands of locations linked to Nazi rule remained unmarked and many forgotten for decades. Commemorative initiatives routinely faced hostility from local and national leaders and the German population, but did important groundwork for the memorials that exist today.

Local citizens’ intitatives as catalysts

This situation began to shift only in the early 1980s. While the student movement of the 1960s has rightly been lauded for the transformation of German political culture, its impact on the commemoration of the Nazi past was initially marginal. The debates of the “1968ers” were important, but did not in fact descend to the concrete level of local histories of persecution and collaboration. What really made the difference – and over the course of the next few decades created the decentralised topography of memory – was the rise of myriad local citizens’ initiatives that began investigating the past and changing the way we discuss it. Sometimes these were coalitions of existing youth or student groups, trade union branches, local (usually green or social democratic) political parties, societies for Christian-Jewish reconciliation, or church members, coming together to find out what happened at a town’s Gestapo offices or a satellite of a concentration camp or the route of a death march. Often, they were so called “history workshops” (Geschichtswerkstätten) – associations of people who were interested in history, but usually without formal academic training. These groups were generally immersed in the alternative milieu (alternative Szene) of peace, women’s, ecological, and anti-authoritarian movement, which gathered at rallies, concerts, bookstores and coffee shops. The history initiatives sprung up all over the Federal Republic and focused on what was going on locally, but quickly networked with each other through annual history festivals, seminars and newsletters.The crucial point here is that the activists’ primary goal was not dismantling the statues that symbolised a memorial culture that they saw as inadequate – though they did practice this kind of “memory protest”. Much more of these activists’ time was consumed by the quiet and slow “memory work” of archival research, conducting interviews, creating exhibits, planning alternative walking tours, and more. In undertaking this work, those involved came to understand the intricate workings of Nazi rule and the local structures of power and resistance and carried this understanding into all branches of society. They demanded – usually against considerable resistance – that the sites of Nazi terror and of Jewish suffering be marked and the perpetrators be named. This was a fundamental shift from earlier monuments that had been vaguely dedicated to the “victims of violent times.” Gradually, politicians and bureaucrats recognized that there was a touristic and educational demand for more critical history and that support for local museums and memorials was in fact good policy.

Re-invention of memorial sites after the reunification – from memory activism to memory establishment

With reunification of the two German states in 1990 came the need to re-invent the large concentration camp memorial sites that the East German state had instrumentalised to bolster its ideological legitimacy. Considerable sums of money were made available for official Holocaust memorial sites – including the large concentration camp sites on German soil, the Topography of Terror memorial in Berlin (among other things, the former Berlin Gestapo headquarters), and the Berlin Holocaust memorial. At all these institutions, former activists, who had dedicated their free time and energy to confronting the Nazi past, and thereby acquired essential skills, now became staff and even leaders. They brought with them the sense that remembering the Holocaust is essential to German democracy and an accomplishment that must be defended against those who argue that it is time to “move on.” As a consequence, Germany today not only has a decentralised landscape of remembrance made up of thousands of markers of the Nazi past, but this is deeply institutionalised and supported by official policy and funding. Democratic memory activism has become the memory establishment.The civic drive to remember in Germany was of course the result of unique circumstances – the passing of the generation responsible during the 1930s and 1940s, the preparatory work done by survivors, artists and intellectuals since 1945, and the emergence of a progressive political environmental buttressed by new social movements. This situation cannot be replicated. But the Equal Justice Initiative (EJI) – the group founded by criminal justice reform advocate Bryan Stevenson, who often draws comparisons between German and US approaches to the past, has nevertheless been inspired by this civic commemoration history.

Centralized and decentralized memory culture in the U.S.

The National Memorial for Peace and Justice in Montgomery, Alabama is at first glance a central site remembering the victims of lynching and racialised terror committed against Black Americans. The companion museum, the Legacy Museum, succinctly depicts the history of racism and violence from slavery, through the Jim Crow era, to police violence against and mass incarceration of African Americans, including children. It is a highly political statement that calls on American society to acknowledge the wrongs committed in the past and to address its reverberations in the present. National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery AL | Foto: Jenny Wüstenberg

National Memorial for Peace and Justice, Montgomery AL | Foto: Jenny Wüstenberg

But even more important here – as well as in Germany – is the process that is necessary to make such decentralised remembrance possible: it cannot be driven from above, but must emerge from civic initiative locally. Citizens must conduct research, practice public engagement, organise walking tours and exhibits – do the memory work, before a broad impact will be felt. And just like after 1945 in Germany, memorials built by civil society are not automatically good for democracy. There are plenty of activists working in the opposite direction, seeking to protect Confederate statues, for example. Making sure memory work is beneficial for democracy requires broad debate and sustained engagement, not just the temporary actions of a few.

This is a lesson that Germans today would do well to revisit. Anti-Semitic and xenophobic attacks (as well as the party-political and social media infrastructures that fan them) are on the rise in the Federal Republic. Long-standing calls to address Germany’s colonial past have only recently acquired a wider audience. Clearly, the existing “topography of memory” in Germany should not be seen as an excuse to lean back and tell others how to best “do over” their past. Civic activism is as needed as ever.