Inspirador How Helsinki Invites Its Citizens to Participate through Playing

It is already common for cities to have channels through which citizens can participate in municipal decisions. However, engaging a large number of people from different backgrounds is always a challenge. Helsinki's proposal? Create a card game!

The Inspirador is rethinking sustainable cities in identifying and sharing inspiring initiatives and policies from more than 32 cities around the world. The research is systemising these cases in categories, these are signified by hashtags.

#democratize_space

The availability of quality public spaces, combined with affordable housing and access to essential city services is a central aspect of a good quality of urban life. Public spaces promote climate equality, environmental awareness, and health benefits, and energize the local economy. Cities that understand that having a home is a basic right are taking steps to democratize access to housing, inspiring other cities around the world.

Submitting a project for the city office involves understanding a rather complex system and comprehending what the whole city needs. Such a complicated process often discourages citizens to participate. As a result, people who want to contribute to their cities are a powerful and frequently underutilized resource.

Thinking about how to facilitate the ideation of citizen projects, the city of Helsinki decided to develop a game. The city needed solid and diverse proposals for the challenge of the municipal budget. In the participatory budget, citizens decide how to allocate part of a municipal or public budget through a democratic deliberation process. And this is where the idea for the game, called Omastadi, which is the same name as the participatory budgeting platform and strategy developed by the city, came about.

The participatory budget scheme was created in Porto Alegre, Brazil, in 1988, and has been adapted by more than 1,500 cities around the world. The Omastadi game, one of the first of its kind in the world, is specifically designed to be played by citizens as part of the participatory budgeting process.

The idea behind the Omastadi game is to, on the one hand, make the participatory budgeting process understandable and inclusive for all, and, on the other hand, to motivate a larger number of citizens to participate. ”The game aims to empower people and guide them on how to create feasible projects that are aligned with the objectives of the city” says Kirsi Verkka, the development manager for the city of Helsinki. It is designed to foster qualities such as equal participation, creativity, and civic learning, and as an initiative of the city administration, it is fully funded by the municipality.

Okay, Cards on the Table

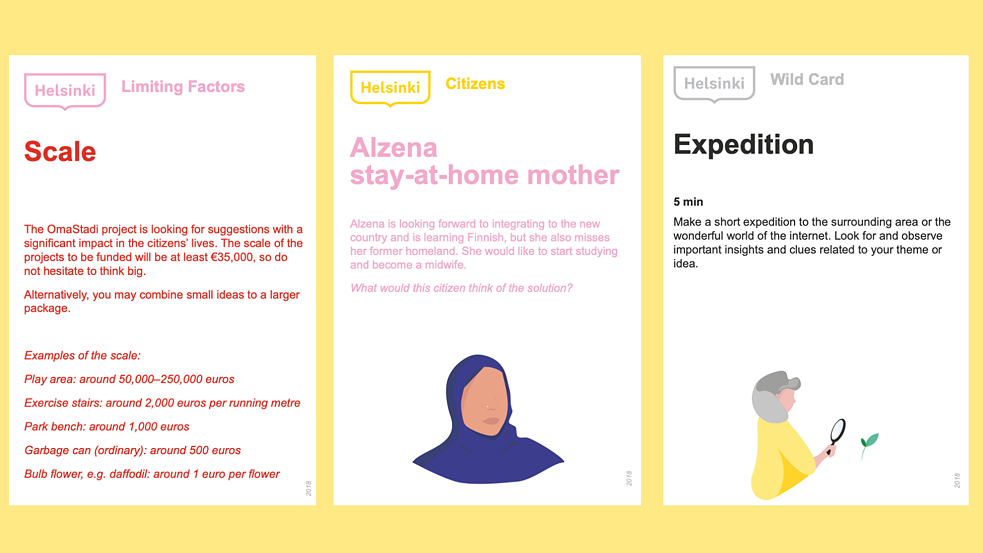

The Omastadi game guides people through a set of steps that help them ideate projects. Players can develop an idea in one hour. Before beginning to play they choose someone to be the director, the scribble and the time keeper.The first part is the brainstorming stage and it starts by posing the question of what kind of Helsinki the players want to build. This step uses a set of “Great City” cards, which present different problems players could focus on, such as a vibrant or sustainable city. After choosing one or two focus themes, the players use the district cards to familiarize themselves with the different areas of the city and choose which place they want to work in.

“Games are helpful in understanding complex processes and concepts. And they’re also much more fun.”

Kirsi Verkka

Following that, the challenge is transforming these ideas into proposals, taking into consideration the limiting factors of participatory budgeting, which are presented in the set of cards. The ideas have to be within reach of the municipal administration, adhere to the city’s values and principles, be one-off projects, and have a budget of at least 35,000 euros. All ideas that don’t fit these criteria at this stage are either put aside or adjusted.

In order to decide which ideas to develop further, the players have to draw the “Great City” cards again and rate their ideas according to which contributes the most for a vibrant, equal, safe and sustainable city. This process helps everyone get on the same page about which idea is the best. Then it is time to present the suggestion to the City of Helsinki.

When the Game Meets the User’s Needs

The game supports players in finding ways to develop their own local neighbourhoods and communities. It also makes the process of striking a compromise between different interests much easier.In his master thesis about the Omastadi game, Andreas Wiberg Sode found out that it strengthened local communities by supporting the development of new networks among the players. One of his interviewees stated that the game made “[...] Helsinki much friendlier. The process showed me the faces of the city.” Nice Hearts, an organisation that works with community-based activities for girls and women of different ages and backgrounds, has been frequently using the game to develop proposals. Their feedback on the game included the aspect of increased inclusivity, one person stated that it gave them “the feeling that [the city] actually recognizes someone who looks like me. I feel a bit more connected to things, and I feel that they know that people like me also live in Finland.”

Omastadi’s Game Development

Laura Lerkkanen is a senior service designer at Hellon, the design agency in charge of developing the game alongside the city of Helsinki. She explained that an important aspect, driving the design of the game, was easy distribution to maintain accessibility. “We also had to think about how much each game unit should cost. Which materials should be used? Could it be reused? How many times?” said Laura. The result was a colourful, compact, and practical card game.The city distributed around 300 units to NGOs and different services in the city. Interested groups of Helsinkis’ citizens can order the game to their regional Borough Liaison.The Omastadi game is now being used by several citizen groups and organizations in Helsinki and has already inspired other cities to develop their own games for similar purposes, like Edinburgh, where Kirsi was invited to give a lecture about the game. In Laura’s view, one key success factor was the commitment of the city to actually make the system work. It is important that the city implements the initiative and is committed to its strategy and higher aim. A list of all registered proposals can be found here.

The Big Picture

In Laura’s view, public entities and government organizations are in a transition period where they need to implement new, more well-suited tools and approaches to regain the feeling of trust, togetherness, and transparency within society. It is also a time when people are looking for new ways to contribute, have an impact and influence their surroundings. Laura argues that the traditional ways of solving problems aren’t working anymore, and that’s why these more creative approaches are needed.“The game really enables having a creative session with your team members or with your friends to make the city better.”

Laura Lerkkanen

What Is This Series About?

The “Inspirador for Possible Cities” project is a collaborative creation by Laura Sobral and Jonaya de Castro aiming to identify experiences among initiatives, academic content, and public policies that work towards more sustainable, cooperative cities. If we assume that our lifestyle gives rise to the factors behind the climate crisis, we have to admit our co-responsibility. Green planned cities with food autonomy and sanitation based on natural infrastructures can be a starting point for the construction of the new imaginary needed for a transition. The project presents public policies and group initiatives from many parts of the world that point to other possible ways of life, categorized into the following hashtags:

#redefine_development, #democratize_space,

#(re)generate_resources, #intensify_collaboration,

#political_imagination

0 Comments