Practicing Together in Solitude:

Imagining New Spaces Beyond Loneliness

Solitude: Loneliness and Freedom is a cultural project by the Goethe-Instituts in East and Central Asia exploring how loneliness and freedom shape our lives today. In Shanghai, the project involved three one-of-a-kind events as well as film screenings, interviews with cultural practitioners, and candid discussions, each providing a different perspective on solitude as a widespread emotional experience.

“Speaking into the Mirror: A Lonely Prologue” was the opening event of the Shanghai edition of Solitude: Loneliness and Freedom. It was held on November 15, 2024, at the German Consulate’s Department of Culture and Education in Shanghai. Curated by Jenny Jiaying Chen and Chen Zhou, it featured a screening of six video films by Chinese artists about social isolation and emotional disconnection during the lockdown years.

The evening program continued with a sharing session, in which participants reflected on the films as tools for self-exploration and connection. From intimate confessions to digital alienation, each film presented a visceral take on solitude today, reframing loneliness as a shared emotional space, which in turn laid the conceptual foundations for the overall project.

“Lost at Home”: Conversations with Returnee Cultural Practitioners

Launched in late 2024, “Lost at Home”, the second event, explores the complex realities facing cultural practitioners who return to China after spending time abroad. Curated by Jenny Jiaying Chen and Chen Yun, the project redefines “diaspora” not just as geographic displacement, but as an ongoing cultural and psychological condition.

In interviews with six cultural practitioners of various generations, each with ties to Shanghai, the project shows how they navigate institutional differences, shifting identities, and the emotional dissonance of feeling “at home” and yet out of place. Their stories reflect diverse motivations for leaving and returning, including academic pursuits, family ties, and personal retreat.

Rather than yielding clear-cut answers, the conversations reveal subtle strategies of reorientation in a more restrictive cultural climate: neither passive adaptation nor outright resistance, but something in between. As co-curator Chen Yun puts it, they open up space to reflect on questions of origins and belonging, and how future generations might forge new paths ahead.

The project also resonated with themes from the third event, “A Retreat for the Retreated”, especially its round-table discussion about the late dissident Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who kept on writing while in prison, and other banned writers and artists who stayed connected through underground networks. These historical examples show that even within repressive systems, alternative forms of connection and creativity can emerge.

“A Retreat for the Retreated”: A Heterotopian Site for Collective Practice

From June 22–24, 2025, “A Retreat for the Retreated” unfolded across two venues, the Department of Culture and Education at the German Consulate General and the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai. With funding from both institutions, the event brought together thirteen alternative art collectives working outside China’s mainstream art centers. Actively engaging in talks, workshops, and group physical fitness sessions, participants effectively co-created a temporary space for shared practice and coexistence.

A round-table discussion on June 22 expanded the project’s scope while asking some critical questions about it: Can an exclusively Chinese lineup truly reflect “curatorial practices in Asia”? Malaysian-born Krystie NG spoke about language anxiety in English-dominated cultural spaces, while Lee Chun Fun from Hong Kong proposed the term “pro-colonialism” to describe current local dynamics, challenging conventional theory and highlighting Asia’s diverse cultural realities.

Moderator Feng Junhua shared his experiences with self-organized groups in Guangzhou and the challenges of forming cross-regional youth communities. The discussion, though brief, revealed a pressing question: Can grassroots collectives still listen to and learn from one another in increasingly polarized times?

The session ended on a lighter note, with Tang Haoduo of The Kindergarten without Walls joking about “resting hours in Hainan” (i.e. the widespread custom of taking a long afternoon nap there), a reminder that local rhythms, rather than barriers, might offer fertile ground for new forms of practice.

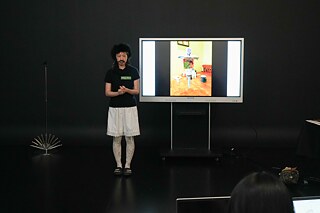

That very afternoon, each of the thirteen collectives presented their work in PechaKucha format – fast-paced, image-driven, and time-limited. While the rapid delivery left the audience with only fleeting impressions, it also made the diversity of approaches strikingly clear. From methodologies and community focus to organizational structures and definitions of success, the differences were so pronounced that no single standard could apply to them all.

Just as the session risked becoming a series of unrelated presentations, an audience member interrupted the one-way flow by suggesting a quick Q&A. By a show of hands, the participants agreed to create an improvised “collective profile”. The resulting snapshot revealed shared realities: small-scale operations, limited resources, non-professional backgrounds, and a strong commitment to local engagement – often in cities they barely know. Few have achieved financial stability, yet almost none has considered giving up. This exchange exposed the tensions within self-organized collectives: the gap between ideals and the structures used to realize them, the uneasy balance between perseverance and fatigue, but also a shared belief in learning through trial and error.

Workshops: Practicing Empathy and Ethics

On June 23, the retreat continued at the German Consulate’s Department of Culture and Education with three workshops focused on rights, responsibilities, collaboration, and ethics. These sessions invited participants to “step into each other’s shoes” by reenacting real-world dilemmas through their artistic practices.

Workshop 1: Between the Individual and the Collective

In “The Theft of a Donation Box”, participants engaged in a situational game exploring how collectives respond to emergencies. Different real-life experiences soon came to light. For many from mainland China, where digital payments predominate, the idea of a physical donation box seemed outdated. Some focused on the risk of theft, but failed to address the game’s core question: How do collectives navigate crises, especially in relation to law enforcement or institutional systems? The role play revealed the challenge of aligning perspectives across different contexts.

Workshop 2: How Do We “Divide Money” in Collective Work?

This session became the day’s emotional and intellectual high point. Moderator Wan Qing introduced a complex real-world case to spark a discussion about how to fairly distribute wages in collective projects. Grounded in reality, the conversation exposed subtle tensions and power dynamics within self-organized structures. Can isolated individuals build truly collaborative systems? Can collectives – once seen as utopian constructs – find dignity and sustainability in imperfect conditions? These questions resonated deeply throughout the room.

Workshop 3: How to Say No: Work Ethics in Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

The third and final workshop was about identity, responsibility, and compromise. It emerged from the discussions that shared ideals often clash with unequal local resources and political or economic constraints. The participants posed questions about the ethics of action and inaction: When is it right to refuse any further compromise? Does taking action always equate with justice? These unresolved questions cast a long shadow over the realities of collective work.

Role Play as a Space for Candid Dialogue

The day-long workshop sessions created a rare opportunity to address complex issues through role play. In this uninhibited environment, participants could express thoughts that might be difficult to air in an everyday setting. By adopting fictional identities, they were able to step into other peoples’ shoes, which turned the exercise into an invaluable rehearsal for confronting sensitive real-life issues.

While differences in past experience occasionally made it impossible to reach a consensus, most participants found the workshops enriching and gained a clearer understanding of the internal dynamics of self-organized collectives. Some, especially those working in education, expressed interest in bringing these methods into the classroom to explore their potential in interactive teaching.

Closing Reflections: Learning from One Another

On the last day of the event, participants gathered at a hot spring to reflect on the retreat. We exchanged insights drawn from our diverse practices, ranging from self-published zines and temporary spaces to grassroots initiatives led by young artists in small towns and artist-led walks through the city streets exemplifying a fluid conception of the artist’s role in society.

These practices represent creative responses to limited resources and have become experiments in coexistence between art institutions in the capitals and alternative spaces and collectives on the outskirts. In this sense, “A Retreat for the Retreated” gave rise to a kind of heterotopian spatial logic that adapts to constraints, reconfigures imaginations and turns loneliness into a starting point for reconnection.

Entanglements of Loneliness and Freedom: Three Dimensions in the Shanghai Context

One crucial question ran through all three events: How are loneliness and freedom connected? They intertwine in complex ways in the unique urban and cultural landscape of Shanghai, along three interrelated axes:

1. Drifting Away from Home

As a city largely shaped by migration, Shanghai embodies the feeling of disconnection from one’s hometown and language. During the pandemic, this sense of dissociation deepened, becoming not just physical, but ideological. The rise of “run” culture (润), a desire to escape from institutional pressures, raises various questions: In a world permeated by a sense of “homelessness”, what gives us a sense of belonging? And when leaving becomes a philosophical principle we believe in, what are we still staying for?

2. The Loneliness of Cultural Workers

For China’s post-1989 generation of cultural practitioners, choosing between staying or leaving has become an existential decision. Echoing East-West Germany’s artistic divide, many seek freedom abroad – yet often fail to find any true sense of belonging there. When creative work has no place in which to take root, it risks being absorbed or silenced. In this context, solitude becomes a crossroads: endure or escape? This tension invites reflection on the evolving role of cultural practices and institutions.

3. The Erosion of Empathy

The pandemic didn’t just isolate people physically, it eroded empathy on a global scale. Since then, lingering fears and ideological divides have hardened cultural boundaries, affecting both the production and the perception of contemporary art. The upshot is a deeper and widely shared sense of solitude that transcends borders and now informs our collective emotional reality.

The evening program continued with a sharing session, in which participants reflected on the films as tools for self-exploration and connection. From intimate confessions to digital alienation, each film presented a visceral take on solitude today, reframing loneliness as a shared emotional space, which in turn laid the conceptual foundations for the overall project.

Launched in late 2024, “Lost at Home”, the second event, explores the complex realities facing cultural practitioners who return to China after spending time abroad. Curated by Jenny Jiaying Chen and Chen Yun, the project redefines “diaspora” not just as geographic displacement, but as an ongoing cultural and psychological condition.

In interviews with six cultural practitioners of various generations, each with ties to Shanghai, the project shows how they navigate institutional differences, shifting identities, and the emotional dissonance of feeling “at home” and yet out of place. Their stories reflect diverse motivations for leaving and returning, including academic pursuits, family ties, and personal retreat.

Rather than yielding clear-cut answers, the conversations reveal subtle strategies of reorientation in a more restrictive cultural climate: neither passive adaptation nor outright resistance, but something in between. As co-curator Chen Yun puts it, they open up space to reflect on questions of origins and belonging, and how future generations might forge new paths ahead.

The project also resonated with themes from the third event, “A Retreat for the Retreated”, especially its round-table discussion about the late dissident Indonesian writer Pramoedya Ananta Toer, who kept on writing while in prison, and other banned writers and artists who stayed connected through underground networks. These historical examples show that even within repressive systems, alternative forms of connection and creativity can emerge.

“A Retreat for the Retreated”: A Heterotopian Site for Collective Practice

From June 22–24, 2025, “A Retreat for the Retreated” unfolded across two venues, the Department of Culture and Education at the German Consulate General and the Rockbund Art Museum in Shanghai. With funding from both institutions, the event brought together thirteen alternative art collectives working outside China’s mainstream art centers. Actively engaging in talks, workshops, and group physical fitness sessions, participants effectively co-created a temporary space for shared practice and coexistence.

A round-table discussion on June 22 expanded the project’s scope while asking some critical questions about it: Can an exclusively Chinese lineup truly reflect “curatorial practices in Asia”? Malaysian-born Krystie NG spoke about language anxiety in English-dominated cultural spaces, while Lee Chun Fun from Hong Kong proposed the term “pro-colonialism” to describe current local dynamics, challenging conventional theory and highlighting Asia’s diverse cultural realities.

Moderator Feng Junhua shared his experiences with self-organized groups in Guangzhou and the challenges of forming cross-regional youth communities. The discussion, though brief, revealed a pressing question: Can grassroots collectives still listen to and learn from one another in increasingly polarized times?

The session ended on a lighter note, with Tang Haoduo of The Kindergarten without Walls joking about “resting hours in Hainan” (i.e. the widespread custom of taking a long afternoon nap there), a reminder that local rhythms, rather than barriers, might offer fertile ground for new forms of practice.

That very afternoon, each of the thirteen collectives presented their work in PechaKucha format – fast-paced, image-driven, and time-limited. While the rapid delivery left the audience with only fleeting impressions, it also made the diversity of approaches strikingly clear. From methodologies and community focus to organizational structures and definitions of success, the differences were so pronounced that no single standard could apply to them all.

Just as the session risked becoming a series of unrelated presentations, an audience member interrupted the one-way flow by suggesting a quick Q&A. By a show of hands, the participants agreed to create an improvised “collective profile”. The resulting snapshot revealed shared realities: small-scale operations, limited resources, non-professional backgrounds, and a strong commitment to local engagement – often in cities they barely know. Few have achieved financial stability, yet almost none has considered giving up. This exchange exposed the tensions within self-organized collectives: the gap between ideals and the structures used to realize them, the uneasy balance between perseverance and fatigue, but also a shared belief in learning through trial and error.

On June 23, the retreat continued at the German Consulate’s Department of Culture and Education with three workshops focused on rights, responsibilities, collaboration, and ethics. These sessions invited participants to “step into each other’s shoes” by reenacting real-world dilemmas through their artistic practices.

Workshop 1: Between the Individual and the Collective

In “The Theft of a Donation Box”, participants engaged in a situational game exploring how collectives respond to emergencies. Different real-life experiences soon came to light. For many from mainland China, where digital payments predominate, the idea of a physical donation box seemed outdated. Some focused on the risk of theft, but failed to address the game’s core question: How do collectives navigate crises, especially in relation to law enforcement or institutional systems? The role play revealed the challenge of aligning perspectives across different contexts.

Workshop 2: How Do We “Divide Money” in Collective Work?

This session became the day’s emotional and intellectual high point. Moderator Wan Qing introduced a complex real-world case to spark a discussion about how to fairly distribute wages in collective projects. Grounded in reality, the conversation exposed subtle tensions and power dynamics within self-organized structures. Can isolated individuals build truly collaborative systems? Can collectives – once seen as utopian constructs – find dignity and sustainability in imperfect conditions? These questions resonated deeply throughout the room.

Workshop 3: How to Say No: Work Ethics in Multi-Stakeholder Collaboration

The third and final workshop was about identity, responsibility, and compromise. It emerged from the discussions that shared ideals often clash with unequal local resources and political or economic constraints. The participants posed questions about the ethics of action and inaction: When is it right to refuse any further compromise? Does taking action always equate with justice? These unresolved questions cast a long shadow over the realities of collective work.

The day-long workshop sessions created a rare opportunity to address complex issues through role play. In this uninhibited environment, participants could express thoughts that might be difficult to air in an everyday setting. By adopting fictional identities, they were able to step into other peoples’ shoes, which turned the exercise into an invaluable rehearsal for confronting sensitive real-life issues.

While differences in past experience occasionally made it impossible to reach a consensus, most participants found the workshops enriching and gained a clearer understanding of the internal dynamics of self-organized collectives. Some, especially those working in education, expressed interest in bringing these methods into the classroom to explore their potential in interactive teaching.

Closing Reflections: Learning from One Another

On the last day of the event, participants gathered at a hot spring to reflect on the retreat. We exchanged insights drawn from our diverse practices, ranging from self-published zines and temporary spaces to grassroots initiatives led by young artists in small towns and artist-led walks through the city streets exemplifying a fluid conception of the artist’s role in society.

These practices represent creative responses to limited resources and have become experiments in coexistence between art institutions in the capitals and alternative spaces and collectives on the outskirts. In this sense, “A Retreat for the Retreated” gave rise to a kind of heterotopian spatial logic that adapts to constraints, reconfigures imaginations and turns loneliness into a starting point for reconnection.

Entanglements of Loneliness and Freedom: Three Dimensions in the Shanghai Context

One crucial question ran through all three events: How are loneliness and freedom connected? They intertwine in complex ways in the unique urban and cultural landscape of Shanghai, along three interrelated axes:

1. Drifting Away from Home

As a city largely shaped by migration, Shanghai embodies the feeling of disconnection from one’s hometown and language. During the pandemic, this sense of dissociation deepened, becoming not just physical, but ideological. The rise of “run” culture (润), a desire to escape from institutional pressures, raises various questions: In a world permeated by a sense of “homelessness”, what gives us a sense of belonging? And when leaving becomes a philosophical principle we believe in, what are we still staying for?

2. The Loneliness of Cultural Workers

For China’s post-1989 generation of cultural practitioners, choosing between staying or leaving has become an existential decision. Echoing East-West Germany’s artistic divide, many seek freedom abroad – yet often fail to find any true sense of belonging there. When creative work has no place in which to take root, it risks being absorbed or silenced. In this context, solitude becomes a crossroads: endure or escape? This tension invites reflection on the evolving role of cultural practices and institutions.

3. The Erosion of Empathy

The pandemic didn’t just isolate people physically, it eroded empathy on a global scale. Since then, lingering fears and ideological divides have hardened cultural boundaries, affecting both the production and the perception of contemporary art. The upshot is a deeper and widely shared sense of solitude that transcends borders and now informs our collective emotional reality.