Artistic Activism “The most important thing is the right to speak for yourself”

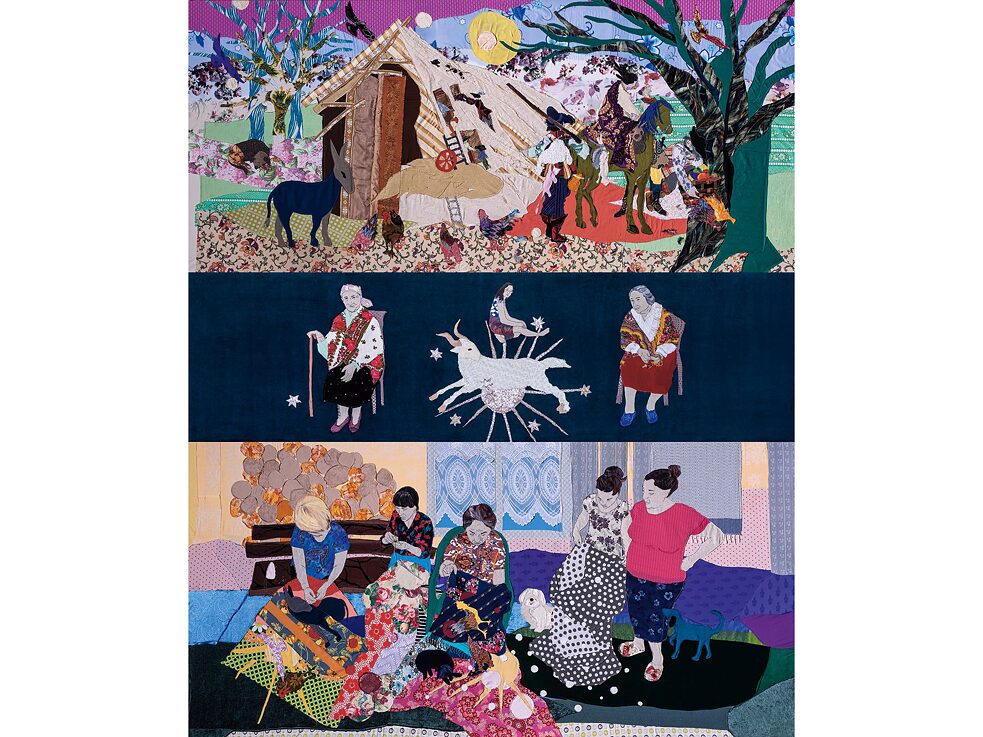

With her textile artworks, the Romani artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas is designing the Polish pavilion at the 2022 Biennale. | Photo (detail): Daniel Rumiancew

Polish-Romani artist Małgorzata Mirga-Tas on artistic activism, the identity of the European Roma community, dignified female protagonists and the struggle for equal rights.

Małgorzata Mirga-Tas is the first Romani artist ever to represent a country at the Venice Biennale. With her work "Re-enchanting the World", she gives Roma communities across Europe their own palace of culture with large-scale fabric frescoes. Mid-September 2022, five months after the opening of the pavilion in Venice, Małgorzata Mirga-Tas finds time late in the evening for an interview. She is about to move to Berlin, where she will be a fellow of the Berlin Artists-in-Residence programme of the DAAD (German Academic Exchange Service), and has just spent additional three days in Czarna Góra in the Sudeten Mountains of southern Poland, not far from the Czech border.Małgorzata Mirga-Tas, Czarna Góra or “Black Mountain” – the very name sounds magical. What’s the place like? What does it mean to you?

It is, above all, my home. When you cross the bridge to Czarna Góra, you’re right in the Roma settlement. We’ve been living here for over four hundred years. In the middle of the forest, in nature, near the mountains. It used to be a small, quiet village, but nowadays more and more tourists are coming to ski here. Sometimes it’s really overrun with tourists.I live here, my whole family’s here. I’m moving to Berlin now, but I hope to be back. Whenever I’m here, I have no desire to leave.

In connection with your art at the Biennale pavilion and in the press, you’re described as a Romani artist and activist. Is that how you see yourself?

I didn’t used to see myself as an activist. I ran educational art projects for children in the settlement. I wanted to do something worthwhile, to help improve the Roma community’s image.

I want to generate more appreciation for Roma through my art.

And I want our community to know our own culture and history and to gain a sense of our worth. Later on, there was this boom and suddenly someone called me an “activist” in an article. And I thought to myself: ok, this is activism that’s important for us. I’m a Romni, I live in a Roma settlement, I have a Roma family. I’m involved in the society. And I love what I do!

Your protagonists are real people. What do you look for in the people you portray?

I don’t actually look for them, I usually find them by chance among the people around me or in history. I want to preserve them for posterity so they won’t be forgotten. Not all of them are well-known figures. Several are known only to some of our families in Czarna Góra and the surrounding villages. Some of the women here are possessed of a special kind of inner dignity. In my opinion, they have a right to be remembered.

In the Biennale pavilion I show female artists, poets and singers, as well as two of my uncles: one was the first Romani student in Poland and is now a poet, the other’s the first Romani geographer in Poland. We’re everywhere and we all know one another, young and old alike. We find personalities like them in every country. There are also pictures of my friends, my sons, my husband, my grandma, my sisters, even my curator. Because our supporters also belong in a work of art about us Roma.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February made me stop and think. I was almost finished working on the pavilion at the time. I did manage to finish a portrait of an Auschwitz survivor from Czarny Dunajec (a village near Czarna Góra), which meant a lot to me. But after that, I did only landscapes: seeing those brutal images of the war, I just couldn’t portray people anymore.

What role do the second-hand fabrics play in your portrayals?

The materials used in my tapestries are from my friends and relatives’ clothes. These fabrics add another emotional level to the pictures, an extra dynamic – precisely because they’re already used, they had a life before the picture. It’s also more environmentally sustainable. We don’t need new fabric.

The sewing process is a meaningful, artisanal, collective work where we women are together, talk a lot and exchange ideas.

Besides your work, the Pavilion catalogue includes some poems by an uncle of yours and a singer from Czarna Góra. How do languages figure in your work?

Romani is my mother tongue: I dream in Romani. I’m also a Polish citizen. So I feel Romani and Polish. But Polish is my second language.

The poems add even more magic and spirituality to the pavilion. The titles of my pictures are always in Romani too. I want to preserve this heritage. Besides, it’s a beautiful language. And I can talk in Romani in any country, just about anywhere in the world. Sure, there are different dialects, but we all understand each other.

You’ve given the Roma community its very own “fresco palace” at the Biennale Pavilion. Roma are the biggest ethnic minority in Europe. And yet they’re marginalized and discriminated against in most European countries. What can art do about the exclusion of minorities?

Art can connect instead of dividing people. It promotes dialogue. It can also influence people. The fact that a Romni is designing a national pavilion at the Biennale goes to show that other Romani artists can make it too.

When the European Roma Institute for Arts and Culture opened in Berlin in 2017, it was the first time we’d ever had a base where we can find support and further develop. Our art was previously sidelined, excluded from the mainstream discourse.

Many friends of mine from other ethnic minorities share in my happiness about the pavilion, seeing it as an opportunity for themselves, too.

This pavilion is an important step towards finally speaking with our own voice as a community. People are always talking about us and speaking on our behalf, mostly without us. Non-Romani artists sometimes show our community from their point of view, without realizing they’re stigmatizing us yet again – even though they think they’re supporting us.

But now we get to tell our own story. And that’s the most important thing: the right to speak for yourself.

In the online tour of the pavilion, your curators say, “The Roma community tie Europe together.” What does that mean?

Yes, we Roma live in every country in Europe, but could do without the separate states. Historically speaking, we’re a very pacifistic people. Whenever a war broke out, we’d leave so as not to have to fight. But sometimes we were forced to, for example in Romania. With our pacifism, we are an example of how to coexist peacefully in Europe.

What also ties us together is that we know how to fight for our rights and visibility across national borders.

Recently, there’ve been reports about Roma groups that fled Ukraine when the Russians invaded but were not as openly welcomed in neighbouring Western countries as other Ukrainians were.

This is really a matter of concern: no one wants to help the Roma from Ukraine, they’re second-class refugees. Romani activists and helpers had to get organized fast because the state agencies were overwhelmed. The arts scene also got involved. So I see this connection between art and activism there, too: I hope my art can do something about this negative image and unfair treatment.

After all, we all want to feel like worthy human beings!

This interview was conducted by Peggy Lohse.

0 Comments