Sonic Culture in Myanmar

The Decline of Burmese Traditional Music

By Lynn Nandar Htoo, 2022Before I dive into an account of Myamnar’s traditional court music, called Mahar Gita, I would like to point to Nusasonic’s Common Tonalities project, led by Khyam Allami in 2022. This project assembled 20 artists to explore Southeast Asian tuning systems and scales through modern music technologies for the creation of new music. Each participant, including myself, brought our own specific interests and knowledge of regional tunings to the group, and through discussion and Khyam’s mentorship I was introduced to many different realms of sound and tuning systems outside of the dominant Western twelve-tone equal temperament system.

Within that project, I looked into the tuning system used in Myanmar's traditional court music. I was astounded by what I learned about my nation's traditional court music and its intricate relationship to its past, present, and future cultural developments. My research introduced me to not only the traditional court music of Myanmar but also the music of numerous peoples and ethnic groups throughout the nation, from the northern hills to the southern regions close to the ocean, and everywhere in between. I'm interested in learning more about these various but somehow connected cultures' sonic worlds. Later in 2022, Nusasonic invited me once more to take part in its closing festival in Saigon, Nusasonic HCMC. There, I met many musicians from Southeast Asia and was further inspired by the ways in which they have been developing and experimenting with their own unique cultures of sound.

In this essay, I will detail my research into Myanmar’s traditional music of the royal court, Mahar Gita. Literally meaning »great music,« Mahar Gita are music ensembles mostly composed of court musicians that were mainly rooted in poetry. I’ll dive into Mahar Gita’s history and present state, and share a few thoughts on how Myanmar’s different local music traditions might flourish in contemporary ways. Burmese court music is the traditional music I'm presenting here, but there are many other musical traditions that also exist and need to conduct research.

On 24 May 2020, this broadcast about »Moe Day War,« a Burmese traditional court song sung by Daw Saw Mya Aye Kyi, was aired by the Burmese Community Broadcasting Group (BCBG), a Burmese radio program at FM 98.5 Sydney.

Mahar Gita, which means »great music« in Sanskrit, refers to historical musical ensembles that were primarily composed of court musicians and had their roots primarily in poetry. The old patronage structures under which Mahar Gita had thrived were dismantled with King Thibaw's exile by British colonization in 1885. The royal musicians of the Mandalay Palace were fired, and they were unable to find work as musicians elsewhere. Under foreign rule, the oral traditions of the Mahar Gita deteriorated further as fewer generations showed an interest in learning them. The last composer of the Mahar Gita, Daw Sa Mya Aye Kyi (1892–1968), expressed her concerns about the Mahar Gita tradition's future due to the lack of commitment from younger generations.

Today Mahar Gita is rarely heard apart from weddings. There are major obstacles in learning it, including a lack of reliable scores. There are a few publications documenting standard practices of Mahar Gita from the 1950s, but scores are not included. Such publications focus exclusively on lyrics and syllables and there is disagreement over the more controversial versions and variations of Mahar Gita.

These traditions continued to expand and be codified into various forms such as Yein (dance), court dances called Anyeint, and songs called Kyo and Bwe, which are still performed relatively often today. In the Bagan Period (9th – 13th Century), King Anawrahta attempted to eradicate Nat and Naga worship, instead promoting Theravada Buddhism. Mon and Pyu cultures, from Thaton and Thaya Khittaya respectively, influenced Bagan and resulted in the amalgamation which became a unique Bagan culture. Frequent relations with Sri Lanka during this period meant that Sri Lankan dancers exerted some influence upon Bagan dancers. The string instrument saung, the wind instrument hnyin, and the crocodile shaped harp mi chaung are first documented in this period.

Notable changes and innovations in traditional court music and dance are recorded in the Inwa Period (14th – 18th Century). Myanmar’s literature also flourished and Minister Padethayaza, who is a composer as well as playwright, wrote a number of Kyo songs. Songs, dances, and theater were performed at court ceremonies and the royal theater. The pat waing (drum circle), kyey waing (brass gong circle), and pattala (xylophone) were widely used in cultural performances. Nat culture flourished again and brass gongs and oboe were played at Nat festivals to create an ambience for Nat spirits.

The ensuing Konbaung Period lasted over a century before the British colonized the entire country in 1885. During the Konbaung period, Myanmar’s traditional court music was highly developed and foreign cultures were introduced to the court. So many artists with creative talent emerged from this period of cross-pollination. Kings and scholars patronized and promoted music, song, dance, and other performing arts. Minister Mya Waddy Mingyi U Sa, Prince Pyin Si, and Princess Hlaing Hteik Khaung Tin were frontliners for playing instruments, song composition, and singing.

»Nagarni« by Gita Lu Lin U Ko Ko is a modern song blending Burmese characteristics and influences from Western instruments.

Performing acts of the Hnaung Khit age underwent innovation and modernization, resulting in new composition styles. Later in the 20th century, the Myanmar government promoted Myanmar Hsaing Waing, a typical musical ensemble that performs songs, music, and dance. Annual performing arts competitions were held to revive and promote Myanmar’s traditional performing arts, although they were not as successful with Myanmar’s general public as expected, as these competitions revolved around the small community of traditional musicians, with very little participation by young students. The National University of Art and Culture in Yangon emerged at this time under the Ministry of Culture. It runs classes in music, dance, drama and visual arts. Western cultural influences furthermore led to the creation of modern songs with Burmese characteristics, for example as composed by Gita Lu Lin U Ko Ko and Sandayar Hla Htut. But Myanmar’s traditional court music did not catch on with younger generations in the 21st century. This is due to several factors, such as having very little scholarly research available.

»Tain Ta Man« by Sandayar Hla Htut is another example of a modern song blending Burmese and Western influences.

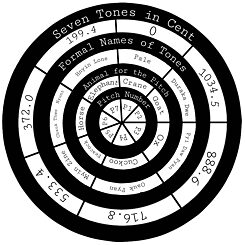

Illustration of Myanmar’s tonalities

For example, the pattala (xylophone), and kyay pattala (bronze xylophone) often have slightly different frequencies for the same pitches. Myanmar musicians use P1, P4, P5, and P7 (C, G, F, and D) as pitch centers, and they make a blended tuning of P6, P5, and P4 (E, F, and G) to avoid accidentals in transposition or modulation. P1, P7, P4, P3 are similar to the diatonic scale of C, D, G, A. P6 is slightly lower than E, P5 is slightly higher than F, and P2 is slightly lower than B. These narrow distances between notes allow for smoother movement. Ancient composers are believed to have used all seven pitches for their compositions, and Mahar Gita musicians commonly choose P1 (pale), P5 (myin zine), P4 (oauk pyan), and P7 (hnyin lone) as pitch centers for Mahar Gita songs. The Pale scale is P1, P7, P6, P4, P3; the Myin Zine scale is P5,P4, P3, P1, P7; Than Yoe is P1,P6, P5, P4, P2, P1; Ngar Bauk Ouk Pyan is P5, P3, P2, P1,P6, P5; and Lay Bauk is P4, P2, P1, P7, P5, P4. The scales use five pitches as main tones and the other two as secondary tones. For Saung string instruments, secondary tones are used by bending the strings. In some tunings for the saung, octaves are tuned differently in the different scales, for scale transition and modulation.

Mahar Gita harmony is based on a two-voice harmony system called twe lone, where the voices are played by only two fingers (thumb and index) on the saung. Harmonic pairs are created by adding a lower line to the active higher melodic line, creating a heterophonic relationship with the accompanying voice part. Nayi (quadruple), walatt (Duple), and walatt amyan (8/16) are common meters of Mahar Gita. Nayi can be 4/2, 4/4, 4/1 and any quadruple can be called Nayi. Triple meters such as 3/4 and 6/8 are rarely used. The tempo in Mahar Gita is not stable, but rather frequently changing and floating. See (a tiny cymbal or bell) and wa (a wood block or wood clapper) play a very important role in defining the meter and controlling the tempo of the piece.

The aesthetic value of Myanmar’s traditional court music is flexibility in performance, and rubato or swing-like nuances. In Mahar Gita, composers usually repeated a theme twice in different ways. The theme is played freely without any specific meter, followed by the same theme played in a rhythmic nayi. As Mahar Gita was developed from reciting poems, the accompaniment improvised following the lead of the voice. Buddhism has a profound influence on the culture of Myanmar. Calmness and a pure state of mind can be found in the musical style of Mahar Gita. The tempos are slow-paced and running notes are played smoothly without little accents, to sound like a long, curved line. Mahar Gita has a subtle aspect of gentleness.

Myanmar’s saung has been used since pre-Phu period. It was a favorite musical instrument at the court and many of the royal family, ministers, and courtiers could play it with skill and talent. In the early periods, the saung had only seven strings, but today they number to sixteen with two bass strings. The saung is one of the earliest musical instruments and the terms of musical scales are derived from it.

Performances by a Myanmar Hsaing Ensemble.

The pattala (Myanmar xylophone) is thought to have begun in the 15th Century from usage of bamboo for musical instruments. It had 17 slats in the past but now the slats have increased to 21. In the past, the Than Hman (tonic note) is freely tuned, however the international diatonic scale is used to tune the pattala nowadays. The pattala slats are not only made from bamboo but also out of metals such as iron and brass. Sadly, today only one iron pattala and one brass pattala with traditional tunings are known to remain, both of which are in Mandalay.

The Hsaing Waing is a harmonious ensemble of many instruments. It was founded during Inwa period around the 14th Century. In the 19th Century, the most recent formation of Hsaing Waing appeared; wooden logs about three feet high and two feet long are pieced together into the shape of a circle, from which 21 drums are hung in a descending musical scale. The hne (oboe), maung saing (gong frame), see, and wa, and a vocalist, the chauk lon pat (six small drums), a pat ma gyi (big drum), and cymbals are played around the saing waing, which leads the ensemble.

Thar Soe blends traditional and contemporary music styles.

Ever since British colonization, Myanmar’s sonic culture has fused with Western musical instrumentation. Myanmar’s traditional instruments are tuned to Western scales, especially the pattala, whose slats have to be made to specific tonalities, contributing to the diminishing use of traditional musical scales. Especially in the age of radio, Western music culture has deeply influenced traditional musicians. Traditional musical tonalities and scales are rarely heard, even in Hsaing Waing ensembles. Referencing the traditional tonalities mentioned above, I encourage new generations of musicians to explore the world of Myanmar’s tonalities with new innovations and modern technology. Not to forget, Myanmar is rich in sonic cultures from different ethnic communities that each embrace their own traditional songs and musics. New sonic creations, musical compositions, and scholarly research are very much in need if we want to discover more deep-rooted and flavorful sonic cultures in Myanmar.

References:

In this essay, I will detail my research into Myanmar’s traditional music of the royal court, Mahar Gita. Literally meaning »great music,« Mahar Gita are music ensembles mostly composed of court musicians that were mainly rooted in poetry. I’ll dive into Mahar Gita’s history and present state, and share a few thoughts on how Myanmar’s different local music traditions might flourish in contemporary ways. Burmese court music is the traditional music I'm presenting here, but there are many other musical traditions that also exist and need to conduct research.

On 24 May 2020, this broadcast about »Moe Day War,« a Burmese traditional court song sung by Daw Saw Mya Aye Kyi, was aired by the Burmese Community Broadcasting Group (BCBG), a Burmese radio program at FM 98.5 Sydney.

Mahar Gita, which means »great music« in Sanskrit, refers to historical musical ensembles that were primarily composed of court musicians and had their roots primarily in poetry. The old patronage structures under which Mahar Gita had thrived were dismantled with King Thibaw's exile by British colonization in 1885. The royal musicians of the Mandalay Palace were fired, and they were unable to find work as musicians elsewhere. Under foreign rule, the oral traditions of the Mahar Gita deteriorated further as fewer generations showed an interest in learning them. The last composer of the Mahar Gita, Daw Sa Mya Aye Kyi (1892–1968), expressed her concerns about the Mahar Gita tradition's future due to the lack of commitment from younger generations.

Today Mahar Gita is rarely heard apart from weddings. There are major obstacles in learning it, including a lack of reliable scores. There are a few publications documenting standard practices of Mahar Gita from the 1950s, but scores are not included. Such publications focus exclusively on lyrics and syllables and there is disagreement over the more controversial versions and variations of Mahar Gita.

A History of Myanmar’s Traditional Court Music

Myanmar’s traditional court music originated around 1,500 years ago. Agriculture, Buddhism, Nat worship culture (a belief that spirits (nat) govern everything in the world), and royal ceremonies are major factors that have contributed to the origin and evolution of these traditional musics through successive periods of time. These musics have been documented in archaeological records since the Thaton Period (5th – 11th Century). The expressions and movements of wind instrumentalists, drum players and little brass cymbal players found on excavated glazed plaques from the ancient cities of Thaton and Pegu in the Mon region show some similarity with present day performers of do:bat (double-headed drum) bands. Indian merchants were already engaged in maritime trade with Myanmar seaport towns and they brought with them their cultural traditions and entertainment including the drama of Rama-yana Jartaka. At the same time during Central Myanmar’s Thayay Khittaya Period (5th – 9th Century), the Pyu cultural troupe accompanied a diplomatic mission to the capital of China (Tang dynasty), which included musical instruments made of brass; wind instruments made of conch shell, horn, and dried gourds; and instruments made of hide, leather, and ivory. Dancers furthermore wore costumes ornamented with gem-studded bangles, rings, armlets, anklets, earrings, and golden headgear.These traditions continued to expand and be codified into various forms such as Yein (dance), court dances called Anyeint, and songs called Kyo and Bwe, which are still performed relatively often today. In the Bagan Period (9th – 13th Century), King Anawrahta attempted to eradicate Nat and Naga worship, instead promoting Theravada Buddhism. Mon and Pyu cultures, from Thaton and Thaya Khittaya respectively, influenced Bagan and resulted in the amalgamation which became a unique Bagan culture. Frequent relations with Sri Lanka during this period meant that Sri Lankan dancers exerted some influence upon Bagan dancers. The string instrument saung, the wind instrument hnyin, and the crocodile shaped harp mi chaung are first documented in this period.

Notable changes and innovations in traditional court music and dance are recorded in the Inwa Period (14th – 18th Century). Myanmar’s literature also flourished and Minister Padethayaza, who is a composer as well as playwright, wrote a number of Kyo songs. Songs, dances, and theater were performed at court ceremonies and the royal theater. The pat waing (drum circle), kyey waing (brass gong circle), and pattala (xylophone) were widely used in cultural performances. Nat culture flourished again and brass gongs and oboe were played at Nat festivals to create an ambience for Nat spirits.

The ensuing Konbaung Period lasted over a century before the British colonized the entire country in 1885. During the Konbaung period, Myanmar’s traditional court music was highly developed and foreign cultures were introduced to the court. So many artists with creative talent emerged from this period of cross-pollination. Kings and scholars patronized and promoted music, song, dance, and other performing arts. Minister Mya Waddy Mingyi U Sa, Prince Pyin Si, and Princess Hlaing Hteik Khaung Tin were frontliners for playing instruments, song composition, and singing.

Hnaung Khit Era (19th century – present)

Mahar Gita, which means »great music« in Sanskrit, refers to historical musical ensembles that were primarily composed of court musicians and had their roots primarily in poetry. The old patronage structures under which Mahar Gita had thrived were dismantled with King Thibaw's exile by British colonization in 1885. The royal musicians of the Mandalay Palace were fired, and they were unable to find work as musicians elsewhere. Under foreign rule, the oral traditions of the Mahar Gita deteriorated further as fewer generations showed an interest in learning them. The last composer of the Mahar Gita, Daw Sa Mya Aye Kyi (1892–1968), expressed her concerns about the Mahar Gita tradition's future due to the lack of commitment from younger generations.»Nagarni« by Gita Lu Lin U Ko Ko is a modern song blending Burmese characteristics and influences from Western instruments.

Performing acts of the Hnaung Khit age underwent innovation and modernization, resulting in new composition styles. Later in the 20th century, the Myanmar government promoted Myanmar Hsaing Waing, a typical musical ensemble that performs songs, music, and dance. Annual performing arts competitions were held to revive and promote Myanmar’s traditional performing arts, although they were not as successful with Myanmar’s general public as expected, as these competitions revolved around the small community of traditional musicians, with very little participation by young students. The National University of Art and Culture in Yangon emerged at this time under the Ministry of Culture. It runs classes in music, dance, drama and visual arts. Western cultural influences furthermore led to the creation of modern songs with Burmese characteristics, for example as composed by Gita Lu Lin U Ko Ko and Sandayar Hla Htut. But Myanmar’s traditional court music did not catch on with younger generations in the 21st century. This is due to several factors, such as having very little scholarly research available.

»Tain Ta Man« by Sandayar Hla Htut is another example of a modern song blending Burmese and Western influences.

Tonalities in Myanmar’s Traditional Court Musics

Myanmar’s traditional court music uses a seven-note scale ordered from high pitch to low pitch, and is divided into five primary tones and two secondary tones that are used for ornamentation. Historically, the notes are linked to certain animal sounds. The tuning or frequencies of this seven-note scale differs from the Western diatonic scale. Furthermore, Myanmar’s traditional instruments tend not to have standardized tuning.Illustration of Myanmar’s tonalities

For example, the pattala (xylophone), and kyay pattala (bronze xylophone) often have slightly different frequencies for the same pitches. Myanmar musicians use P1, P4, P5, and P7 (C, G, F, and D) as pitch centers, and they make a blended tuning of P6, P5, and P4 (E, F, and G) to avoid accidentals in transposition or modulation. P1, P7, P4, P3 are similar to the diatonic scale of C, D, G, A. P6 is slightly lower than E, P5 is slightly higher than F, and P2 is slightly lower than B. These narrow distances between notes allow for smoother movement. Ancient composers are believed to have used all seven pitches for their compositions, and Mahar Gita musicians commonly choose P1 (pale), P5 (myin zine), P4 (oauk pyan), and P7 (hnyin lone) as pitch centers for Mahar Gita songs. The Pale scale is P1, P7, P6, P4, P3; the Myin Zine scale is P5,P4, P3, P1, P7; Than Yoe is P1,P6, P5, P4, P2, P1; Ngar Bauk Ouk Pyan is P5, P3, P2, P1,P6, P5; and Lay Bauk is P4, P2, P1, P7, P5, P4. The scales use five pitches as main tones and the other two as secondary tones. For Saung string instruments, secondary tones are used by bending the strings. In some tunings for the saung, octaves are tuned differently in the different scales, for scale transition and modulation.

Mahar Gita harmony is based on a two-voice harmony system called twe lone, where the voices are played by only two fingers (thumb and index) on the saung. Harmonic pairs are created by adding a lower line to the active higher melodic line, creating a heterophonic relationship with the accompanying voice part. Nayi (quadruple), walatt (Duple), and walatt amyan (8/16) are common meters of Mahar Gita. Nayi can be 4/2, 4/4, 4/1 and any quadruple can be called Nayi. Triple meters such as 3/4 and 6/8 are rarely used. The tempo in Mahar Gita is not stable, but rather frequently changing and floating. See (a tiny cymbal or bell) and wa (a wood block or wood clapper) play a very important role in defining the meter and controlling the tempo of the piece.

The aesthetic value of Myanmar’s traditional court music is flexibility in performance, and rubato or swing-like nuances. In Mahar Gita, composers usually repeated a theme twice in different ways. The theme is played freely without any specific meter, followed by the same theme played in a rhythmic nayi. As Mahar Gita was developed from reciting poems, the accompaniment improvised following the lead of the voice. Buddhism has a profound influence on the culture of Myanmar. Calmness and a pure state of mind can be found in the musical style of Mahar Gita. The tempos are slow-paced and running notes are played smoothly without little accents, to sound like a long, curved line. Mahar Gita has a subtle aspect of gentleness.

Instruments

Myanmar’s musical instruments can be classed into kyey (bronze or brass instruments), kyo (string instruments), thayey (instruments made of leather or hide), lei (wind instruments) and let khut (clapper). Among all different kinds of instruments, saung (harp), pattala (xylophone) and saing (drum circle) are mainly used. Instruments like the saung (harp) and saing waing (drum ensemble) are based upon the five pentatonic tones.Myanmar’s saung has been used since pre-Phu period. It was a favorite musical instrument at the court and many of the royal family, ministers, and courtiers could play it with skill and talent. In the early periods, the saung had only seven strings, but today they number to sixteen with two bass strings. The saung is one of the earliest musical instruments and the terms of musical scales are derived from it.

Performances by a Myanmar Hsaing Ensemble.

The pattala (Myanmar xylophone) is thought to have begun in the 15th Century from usage of bamboo for musical instruments. It had 17 slats in the past but now the slats have increased to 21. In the past, the Than Hman (tonic note) is freely tuned, however the international diatonic scale is used to tune the pattala nowadays. The pattala slats are not only made from bamboo but also out of metals such as iron and brass. Sadly, today only one iron pattala and one brass pattala with traditional tunings are known to remain, both of which are in Mandalay.

The Hsaing Waing is a harmonious ensemble of many instruments. It was founded during Inwa period around the 14th Century. In the 19th Century, the most recent formation of Hsaing Waing appeared; wooden logs about three feet high and two feet long are pieced together into the shape of a circle, from which 21 drums are hung in a descending musical scale. The hne (oboe), maung saing (gong frame), see, and wa, and a vocalist, the chauk lon pat (six small drums), a pat ma gyi (big drum), and cymbals are played around the saing waing, which leads the ensemble.

Mahar Gita Today

Mahar Gita, a once highly sophisticated form of music, has fallen out of favour in the 21st century. Today Mahar Gita is rarely heard apart from weddings. There are major obstacles to learning it, including a lack of reliable scores and documentation. There are a few publications documenting standard practices of Mahar Gita from the 1950s, but scores are not included. Instead, such publications focus exclusively on lyrics and syllables, and there is disagreement over the more controversial versions and variations of Mahar Gita. In addition, older generations of traditional court musicians in Myanmar are resistant to new fusions and creations in the genre and have a strong dislike for changing well-established songs. For example, when the singer Thar Soe combined dance and traditional songs from Myanmar, he received numerous criticisms from both the government and traditional court musicians.Thar Soe blends traditional and contemporary music styles.

Ever since British colonization, Myanmar’s sonic culture has fused with Western musical instrumentation. Myanmar’s traditional instruments are tuned to Western scales, especially the pattala, whose slats have to be made to specific tonalities, contributing to the diminishing use of traditional musical scales. Especially in the age of radio, Western music culture has deeply influenced traditional musicians. Traditional musical tonalities and scales are rarely heard, even in Hsaing Waing ensembles. Referencing the traditional tonalities mentioned above, I encourage new generations of musicians to explore the world of Myanmar’s tonalities with new innovations and modern technology. Not to forget, Myanmar is rich in sonic cultures from different ethnic communities that each embrace their own traditional songs and musics. New sonic creations, musical compositions, and scholarly research are very much in need if we want to discover more deep-rooted and flavorful sonic cultures in Myanmar.

References:

- Htut, Sandayar Hla, Myanmar Gita Yaysichaung, SKCC Myanmar Book, Third Edition, 2018.

- Ko, Wai Hin Ko, »A Cross-Cultural Composition with Myanmar and Western Musical Languages,« Thesis Dissertation for Master of Fine and Applied Art in Music and Performing Arts, Faculty of Music and Performing Arts Burapha University, 2021.

- Peters, Joe, Sonic Orders in ASEAN Music: A Field and Laboratory Study of Musical Cultures and Systems in Southeast Asia, ARMOUR Publishing Pte Ltd, ASEAN Committee on Culture and Information, 2003.