Guest Blogger James

The History of the Future

What can the misfits, rebels and bohemians of early 20th century Germany tell us about contemporary life?

There’s no greater threat to your self-image as a free thinker than looking back on your life and seeing a series of formulaic outcomes. Leaving Sydney to become another expat struggling to make it in London? Working long hours at a stressful bean-counting job to pay off a mortgage? Then ditching it all to move to Berlin with vague hopes of a more creative existence?

This catalogue of clichés is my life.

James J. Conway.

| © Miles Staveley

But if they were clichés, why couldn’t I see them coming? Why didn’t I pay more attention in high school and actually learn some German rather than inventing new ways to undermine Mr Garan’s customary good cheer, before settling on French because it seemed the easier option? In fairness it was a stretch for teenage me to imagine future me in another millennium, on another continent, with a German passport, a German stepdaughter and a German attitude to crossing on red (never).

James J. Conway.

| © Miles Staveley

But if they were clichés, why couldn’t I see them coming? Why didn’t I pay more attention in high school and actually learn some German rather than inventing new ways to undermine Mr Garan’s customary good cheer, before settling on French because it seemed the easier option? In fairness it was a stretch for teenage me to imagine future me in another millennium, on another continent, with a German passport, a German stepdaughter and a German attitude to crossing on red (never).

So the prep work for this new life came late. In London I hatched a secret linguistic escape plan – getting a German tutor, and sneaking off to the Goethe-Institut in South Kensington to borrow books and films. Thus began the long journey of grinding frustration and periodic breakthrough that is adult language learning, which eventually resulted in a German-to-English translation diploma. So as the 2010s dawned I was settled in Berlin, beginning a new career translating everything from annual reports and data protection notices to museum exhibition texts and interviews with theatre directors. It was a major improvement, certainly more creative, but still – not quite the epiphany I had hoped for.

WHERE AM I?

A funny thing happens when you move to a new city. As well as finding your way around (how do I navigate the U-Bahn? Where are the best flea markets?) you orient yourself in time. With no German background I was free to pick my own points of identification from the country’s history. Naturally Berlin offers you plenty of past, a lot of it fairly recent and harrowing. Then there’s the Weimar Republic – sexy, edgy and inventive, which the city is evidently both revisiting and reliving. Babylon Berlin is a worldwide hit, centennial Bauhaus commemorations are everywhere, while the city’s hunger for all-night partying and transgressive culture is as strong as it was in the 1920s (although the current far-right resurgence is really overdoing the whole retro thing). Conflicting messages on a bike stand, Berlin.

| © James J. Conway

But what came before? From the Wilhelmine era (1890-1918) I could summon little more than a mental image of the Kaiser who gave his name to the period, scowling under a pointy helmet; his authoritarian reign I took to be a time of conservatism and conformity. I had a vague handle on the causes of World War One, but the literature of the era? I drew a blank.

Conflicting messages on a bike stand, Berlin.

| © James J. Conway

But what came before? From the Wilhelmine era (1890-1918) I could summon little more than a mental image of the Kaiser who gave his name to the period, scowling under a pointy helmet; his authoritarian reign I took to be a time of conservatism and conformity. I had a vague handle on the causes of World War One, but the literature of the era? I drew a blank.That very absence was fascinating. And the surprising innovations of the era were hiding in plain sight. Like many visitors to Berlin I admired the city centre Hackesche Höfe complex, designed by August Endell in 1906. Curious to know more, I discovered a book the architect wrote around the same time (The Beauty of the Metropolis), an exhilarating essay which so completely captured my feelings about personal connections to place and history that it read like a transcript of my own thoughts. A text from the past was describing my present and even pointing the way to my future, even if I didn’t know it then.

The historic village of Rixdorf (now part of Berlin).

| © James J. Conway

I kept reading – about Endell’s friend, the ‘bohemian countess’ Franziska zu Reventlow, and the rest of their Munich circle (yes, Munich was an avant-garde hub in the early 20th century – who knew?). Everything that we associate with the Weimar era, the artistic daring, liberated lifestyles and plans for a better world – it’s all there.

The historic village of Rixdorf (now part of Berlin).

| © James J. Conway

I kept reading – about Endell’s friend, the ‘bohemian countess’ Franziska zu Reventlow, and the rest of their Munich circle (yes, Munich was an avant-garde hub in the early 20th century – who knew?). Everything that we associate with the Weimar era, the artistic daring, liberated lifestyles and plans for a better world – it’s all there.I set about learning as much as I could about the (counter)culture of the period. I would regularly return from the Staatsbibliothek – the beautiful Modernist library in Wings of Desire – with piles of books, I hunted down original editions in second-hand bookshops and even collected postcards from the era. I went searching for the rebels and the dreamers and I was rewarded with radical works of both fiction and non-fiction, contemporary texts that just happen to be a hundred-plus years old. And over and over I wondered: how had I missed this amazing progressive heritage? Why did it seem more or less forgotten in Germany, even? And (epiphany approaching …) why had so little of it ever been translated into English?

And there it was! My creative mission.

SEX, DEATH AND PAPERBACKS

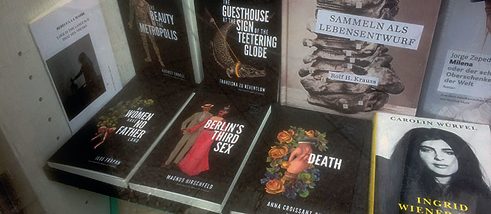

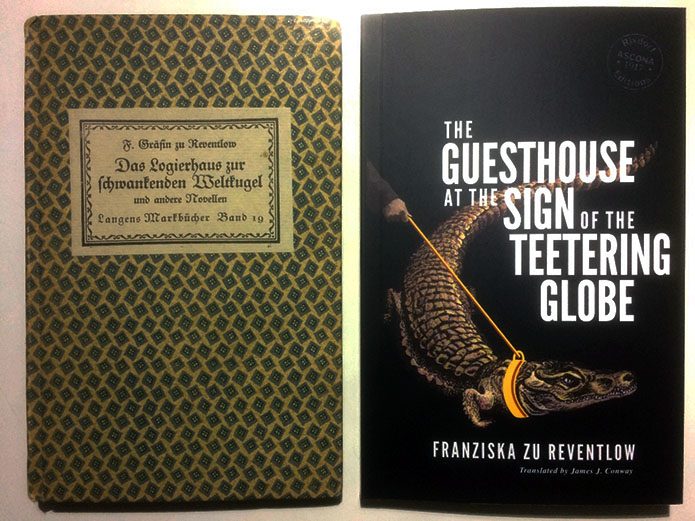

So in 2017 I embarked on a new phase of literary translation to bring these riches to English-speakers and, studiously ignoring my utter lack of publishing experience, formed a (very) small press called Rixdorf Editions. As well as Endell and Reventlow, Rixdorf has issued translations of Magnus Hirschfeld’s astonishing account of early 20th century queer life (Berlin’s Third Sex), experimental fiction by Anna Croissant-Rust (Death) and a visionary feminist novel by Ilse Frapan (We Women Have no Fatherland). I have the same challenges as any independent publisher. Just getting noticed is difficult. Yet slowly these neglected treasures have gained US and UK distribution, positive reviews and a small but growing readership. Short stories by Franziska zu Reventlow; German and English first editions, 100 years apart.

| © James J. Conway

To be clear – Wilhelmine Germany is not an era I long to inhabit. Instead, I respect it as the unacknowledged source of much that we hold to be modern, of works that describe the contemporary condition. Sometimes uncomfortably so; my next translation is an 1894 book of interviews with public figures of the time by Austrian author Hermann Bahr called Antisemitism, investigating a subject that – tragically – hasn’t gone away.

Short stories by Franziska zu Reventlow; German and English first editions, 100 years apart.

| © James J. Conway

To be clear – Wilhelmine Germany is not an era I long to inhabit. Instead, I respect it as the unacknowledged source of much that we hold to be modern, of works that describe the contemporary condition. Sometimes uncomfortably so; my next translation is an 1894 book of interviews with public figures of the time by Austrian author Hermann Bahr called Antisemitism, investigating a subject that – tragically – hasn’t gone away.I have found endless inspiration in the liberated spirits of early modern Germany and their rejection of formulaic thinking. The least I can do is share their legacy.