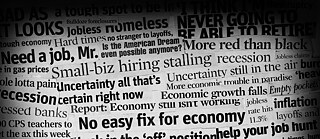

We live in a world of fake news

Stories calling Hillary Clinton a child-trafficker that circulated during the American presidential campaign in 2016, advertisements urging you to invest in the ‘deal of a lifetime’ or ‘scientific findings’ about the harmfulness of Covid-19 vaccines. What do these subjects have in common? The fact that they are false and based on fake news.

By Piotr Henzler

These examples of false information are just the tip of the iceberg. At any rate, no one could compile a full list of these news items, with new, more-or-less invented stories coming fast and furious. Nonetheless, it is no accident that the first example ties in to an American presidential campaign of nine years ago, for this was when the concept of fake news entered mainstream circulation.

Though the story of fake news is as old as the hills, in recent years it has had its ‘golden era’. What might we find? Let’s begin with perhaps the most perilous form of false information, known as deep fakes. These are videos (some would include graphics and photographs) that are created or, maybe worse, altered by AI (Artificial Intelligence). The result? Using a real recording of our favourite actor, we can alter his statement so he says ‘happy birthday’ to a loved on. Or we may swap the head of a stuntman jumping from a bolting horse with our own, and then brag about our dexterity and courage.

But we can also use the capabilities of technology for scams, manipulation, mockery, or to compromise others.

Deep fakes and ‘ordinary’ fakes

Doctored videos are not the only form of fake news. In the (mainly virtual) public space, there is heaps of textual information that people think is true, or reliable, but in fact is wholly or partly invented. It may look like a news article, an interview with experts, an ad, guide or even ‘statements of witnesses’ who had access to ‘secret documents’, now being revealed.This was the case with ‘Pizzagate’ during the American presidential campaign, as it was with hundreds of offers for an ‘attractive investment with guaranteed high returns’, which were ‘advertised’ by celebrities and famous faces from business or sports, with Elon Musk topping the list, translating, according to National Bank of Poland estimates, into losses of around three hundred million zloty for thousands of Poles. The same went during the uptick of the Covid-19 epidemic, when Polish media (and others) was flooded with a wave of unsettling information about harmful vaccines, including suspicions that ‘they’re implanting us with microchips to monitor us’.

New technologies make it possible to create manipulated content that is barely distinguishable from the truth. That’s why critical thinking and fact-checking have become essential tools in navigating today’s digital landscape. | © Goethe-Institut

What is fake news, anyway?

The common denominator of most definitions is the assumption that this is information that is at least partly false, and created to intentionally mislead readers. This ‘falsity’ may involve providing pseudo-facts, manipulating readers so that they read real information but arrive at erroneous conclusions, referring to non-existent source data, presenting an inaccurate or insufficient context for the information…

Some have also included information that is parodical and arises from the author’s mistake or ignorance, but more recently it has been accepted that the intention matters, and so do the potential consequences of spreading this information.From the Internet and… our loved ones

It is easiest to blame the Internet for the spread of fake news, and especially social media. There is a lot of truth in this. Yet we cannot forget that false information is also found in traditional media and in every other place where information is exchanged.According to research conducted by Firm Public Relations, the Demagog Association and Digital Poland in 2024, 57% of respondents received false information from a family member or someone else close to them! Social media also scored high – almost half of respondents (49%) came across fake news there, and one in four received a link to false information through a web communicator.

In general, according to the same research, four out of five residents of Poland have come in contact with fake news. Does this mean the remaining 20% got lucky? Maybe, or perhaps these people don’t know that some of the news they have read was actually false. For it is hard to be an active consumer of media of any kind or a participant in social life and not come across some fake news.

How much is fake news?

A few years ago there were attempts to come up with the overall amount of fake news. At present, the available and reliable data generally pertains to selected categories, concrete channels of communication or markets in which they appear. For instance, according to the British ACE agency, affiliated with the British Home Office, over eight million deep fakes will appear in 2025. This number alone is impressive, but so is the fact that two years before there were ‘only’ 500,000.And fake news in spoken or written form? This is probably inestimable. This information includes not only the ‘original information’ invented by someone somewhere, but also commentaries, commentaries on commentaries, discussions etc. Sometimes produced by unconscious and gullible readers, sometimes by people hired to spread fake news, and increasingly, not created or multiplied by someone, but by something – by Artificial Intelligence, programmed to create, share and comment on false information.

Here we see less the odd piece of untrue information than a planned and complex disinformation campaign aiming to change (or confirm) the views of large or enormous groups of people, sometimes whole societies. From this standpoint, disinformation may affect elections, military affairs, relations between social groups, etc. In actions of this sort, the aim is not quick financial gain, it is an attempt to influence elections, generate fear or tension, build support for a cause, viewpoints or even a state.

What do we say to this?

The awareness of the existence of fake news is on the rise, though this does not always go hand-in-hand with a consciousness of the danger it causes. According to Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism research (2025), around 60% of readers are concerned about whether information online is true or false. Interestingly enough, this wariness is found in 73% of the inhabitants of Africa, 68% of the inhabitants of the United States, and only 54% of the inhabitants of Europe.This means that nearly half the people do not acknowledge the existence of fake news! Why? We do not know. We do know, however, that the creators of fake news do all they can to make us believe their false information. They know what works on people, what features or methods of writing make us more likely to believe doctored or utterly invented information. And they make use of this knowledge.

Have a look at the following articles in our series and find out why we believe in fake news. And then read how critical thinking and the CRAAP test can help us to recognise fake news and can protect us from more or less costly errors – from being mocked among friends when we share some made-up nonsense someone has invented, to more serious costs, such as our money, health or convictions.

The publication of this article is part of PERSPECTIVES – the new label for independent, constructive, and multi-perspective journalism. The German-Czech-Slovak-Ukrainian online magazine JÁDU German-Czech-Slovak-Ukrainian online magazine JÁDU is implementing this EU co-financed project together with six other editorial teams from Central and Eastern Europe, under the leadership of the Goethe-Institut.>>> More about PERSPECTIVES