Smart Cultural City: “Instagrammability” in Art, Architecture and Hybrid Art Spaces

By Ludovica TomarchioHybridArtSpaces explores the relation of physical art spaces and online interaction with art in Singapore. Cities and culture have always evolved in dialogue. This dialogue was often mediatised by the technology and means of representation of the time: the Renaissance city and perspective drawings, the romantic city and literature, the industrial city and cinema, and now, the contemporary city and the internet. Perception of arts and urban spaces in particular have seen significant shifts with the advent of social media. More and more content about arts and urban space is now shared online.

HybridArtSpaces uses methods from digital humanities in relation to urban studies to tackle the following questions: Can we learn more about the interrelation of art production and consumption in a new hybrid cyber-physical reality? Can we discern emergent physical spatial clusters from digital usage patterns? Can we postulate a hybrid art spaces in Singapore?

HybridArtSpaces locates art venues such as artist studios, museums, galleries, monuments, and public spaces and juxtaposes these with geo-tagged social media content grabbed from Instagram, Twitter. The findings are interpreted using machine learning techniques described in the research links below.

How to use HybridArtSpaces? This website represents a graphic content explorer for hybrid art spaces in Singapore. Select one or multiple indicators on the right side such as ‘Type of Art’, ‘Use of Space’, ‘Indoor/Outdoor’. Indicators also include processed information derived from machine learning and statistical analysis such as ‘Topic Diversity’ or ‘Sentiment Analysis’. Browse the media content appearing on the left side. Explore the spatial distribution on the map below or filter by venue location.

Have fun exploring the HybridArtSpaces of Singapore here: http://www.hybridartspaces.com!

-

The combination of social media and its capacity for sharing content with peers — in a digital environment through mobile recording devices— creates a special relationship with space and art.

There is an observed trend in disciplines with experiential aspects such as design, exhibition design, architecture, and public space design, the growing tendency to include particular spatial settings that trigger a desire to document and share on visual social networking platforms like Instagram. This feature is commonly referred to using the term “Instagrammable”. The development of this trend is visible in recent exhibitions and art spaces that are only meant to be “Instagrammable” [i]. The trend is also exacerbated by clients, who specify “Instagrammability” in the design brief, especially for commercial projects. This has even prompted Australian architect Scott Valentine to craft an Instagram guide to design [ii]. I will explore the relationship between Instagram and art, and between Instagram and architecture.

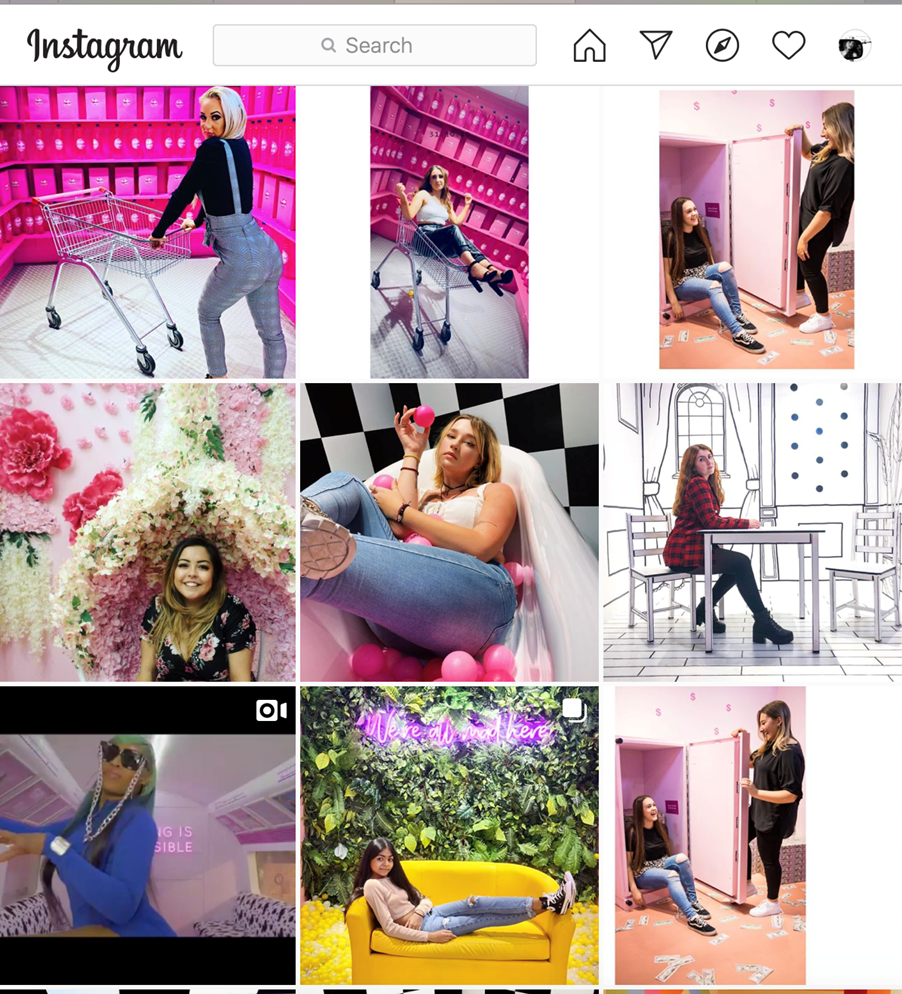

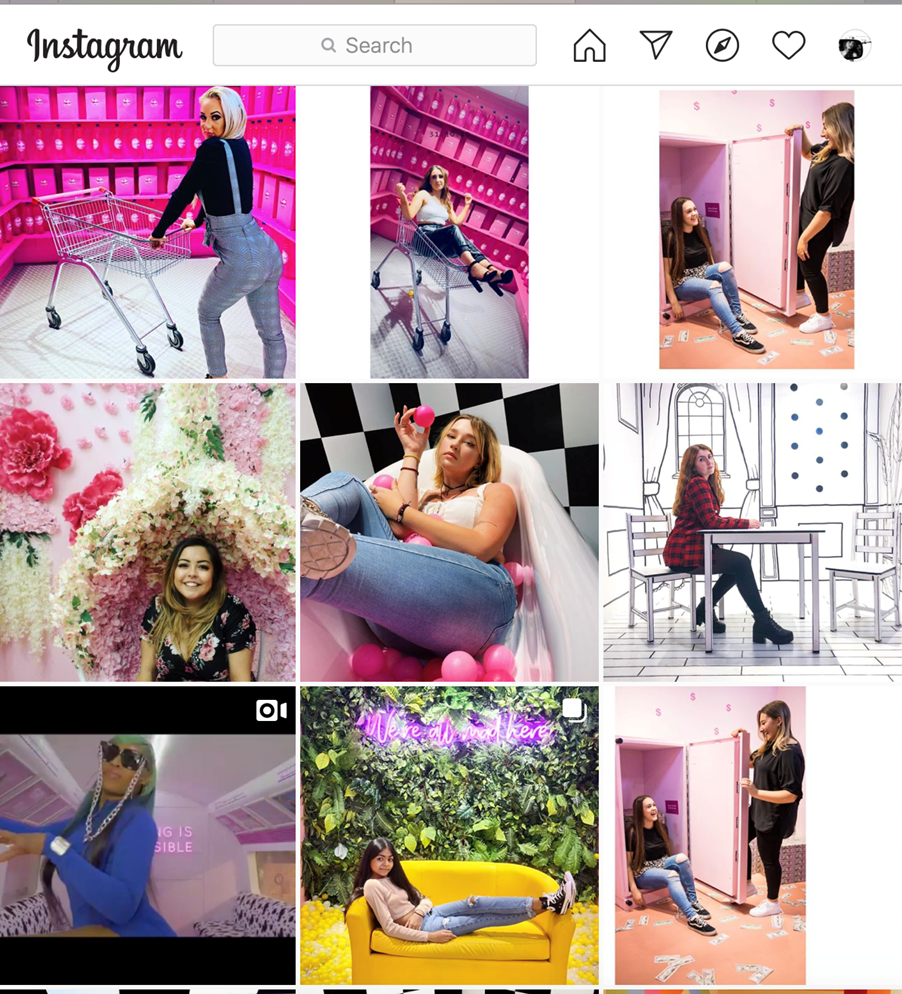

Figure 1. selfie factory Instagram account. Source: https://www.instagram.com/selfiefactoryofficial/, 2020

| © Selfie Factory

Figure 1. selfie factory Instagram account. Source: https://www.instagram.com/selfiefactoryofficial/, 2020

| © Selfie Factory

Instagram architecture

There are two phenomena to consider when deconstructing the relationship between architecture or the built environment and Instagram. From one side, people use Instagram while visiting and navigating space as a place for self-expression and communication; on the other side, designers are trying to anticipate social media attention, designing spaces specifically through the lens of Instagram, sometime without fully understanding the phenomenon of how social media and their feedback loops operate.

In order to have their buildings shared in social media, Alexandra Lange (2014) argues that there is an increasing tendency to simplify of the message, to make it fit to the format of the Instagram app and to be viewed in a state of distraction on small mobile screens, with spaces being designed to be understood instantaneously. Therefore, the message has to be immediate, like a ready-made slogan. In this sense, the architecture of the office BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group Office) offers an example: if the form is carrier of a message, the message through the form can be over-simplified, similar to the duck example of famous architect theoreticians of the 20th century Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown [i], with a ready-made slogan symbolically represented in an iconic shape [ii].

The other trend is to address the “Instagrammability” per se, by providing colour and lighting that suit the picture-taking progress. Other specific features, like a selfie wall or physically printed hashtags, might be integrated in the environment [iii]. Tom Wilkinson highlights that the influence of social media has reduced the designer’s role to provide jazzy backdrops and quirky props, flattening the world into a selfie stage set, sometimes impractial as a physical exhibition space in the use of sleek but unsustainable materials [iv]. In doing so, citizens become users that navigate a controlled space in search for a controlled aesthetic, as argued by Fiocco and Pistone (2019): “Even the idea of a city being a collective political project gets easily forgotten in the swamps of neoliberals,as quality of life becomes a commodity for those with money; those who can gain access to the hyper-surveilled, sleek-looking attractions on offer” [v].

In practice, when designing a spatial venue with social media in mind, there might be more than one phenomenon at stake than just the backdrop or the slogan. Rather than designing perfect backdrops, designers should focus on designing environment where people can identify themselves and interact with the space and the social media.

Manovich points out there are three different types of Instagram users, where the majority of them do not seek for a specific polished aesthetics and simply use the social media to document their life and to build up their personal identity though the images [vi]. Considering the general audience that use social media, the attempt to capture physical space and include it in personal social media feeds should be intended as a way to construct personal identities.

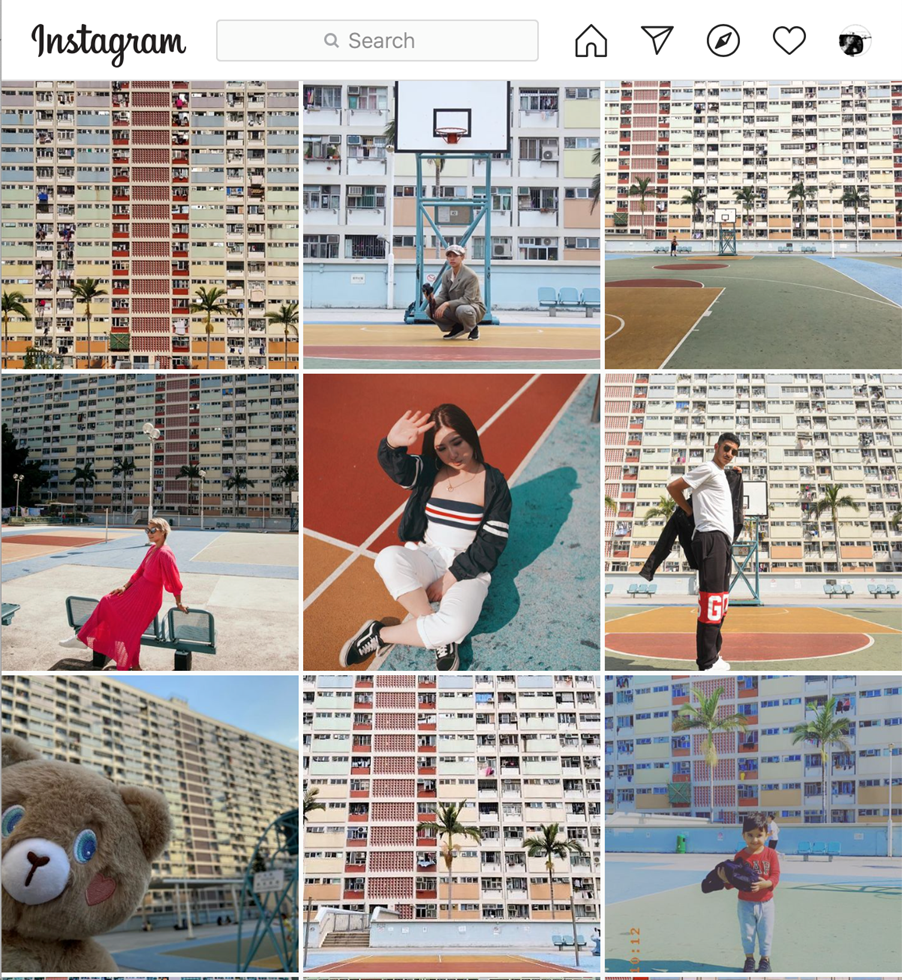

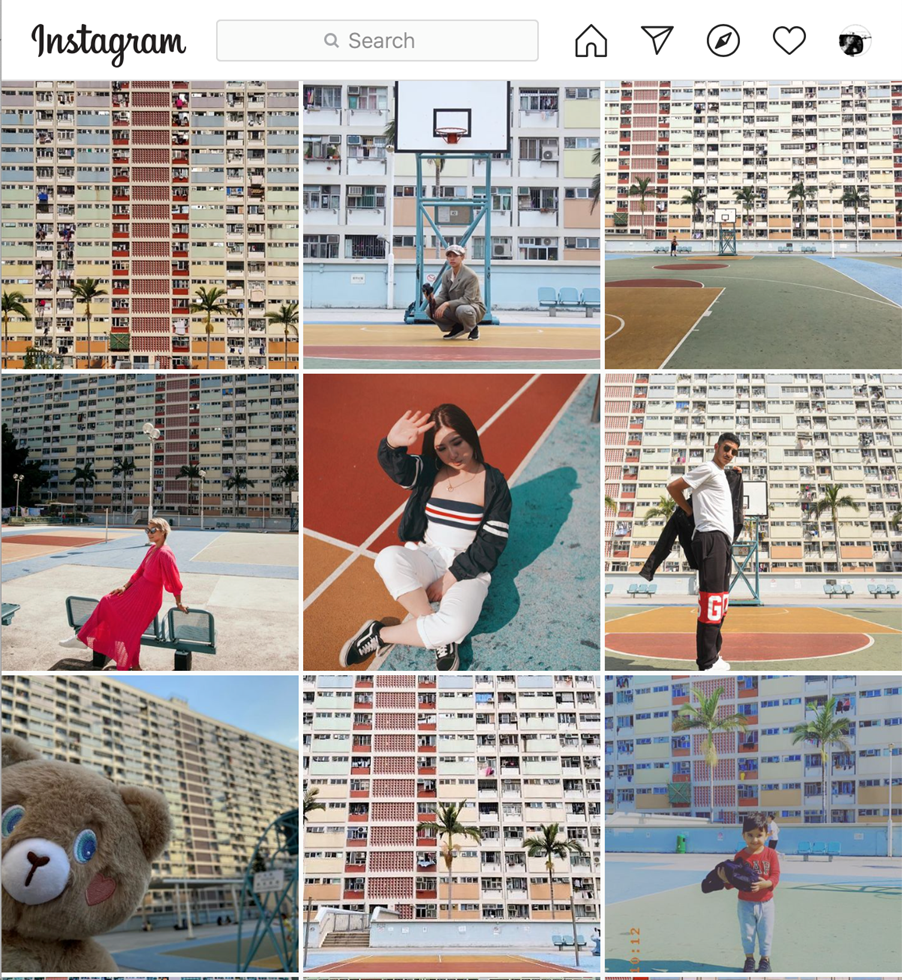

In this sense, the features providing the “Instagrammability” of spaces get a different angle of interpretation. To give some examples, one feature that is strongly advised in Valentine’s “Instagrammable” guide is transparency. While Mimi Zeiger suggests that viral trends might follow advances in rendering technology — therefore including transparency in the image, the solution might follow a different logic, with transparency being widely appreciated as it gives the possibility to include the person within the built environment[vii]. Many locations that are highly appreciated by Instagram users, like the social housing in Hong Kong, are considered expressions of the sublime, expressing a strong relationship between emotions and landscape (Figure 2). If considered under those lenses,the “Instagrammability” of places actually pushes for a stronger relationship between spaces and people, while at the same time encouraging people to explore, visit and actually go to places. The trend of people looking out for locations to include in their feeds is a confirmation that places and spaces matter. Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].

Figure 2. social housing in Hong Kong Instagram location.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/611757194/choi-hung-estate/, 2020

Figure 2. social housing in Hong Kong Instagram location.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/611757194/choi-hung-estate/, 2020

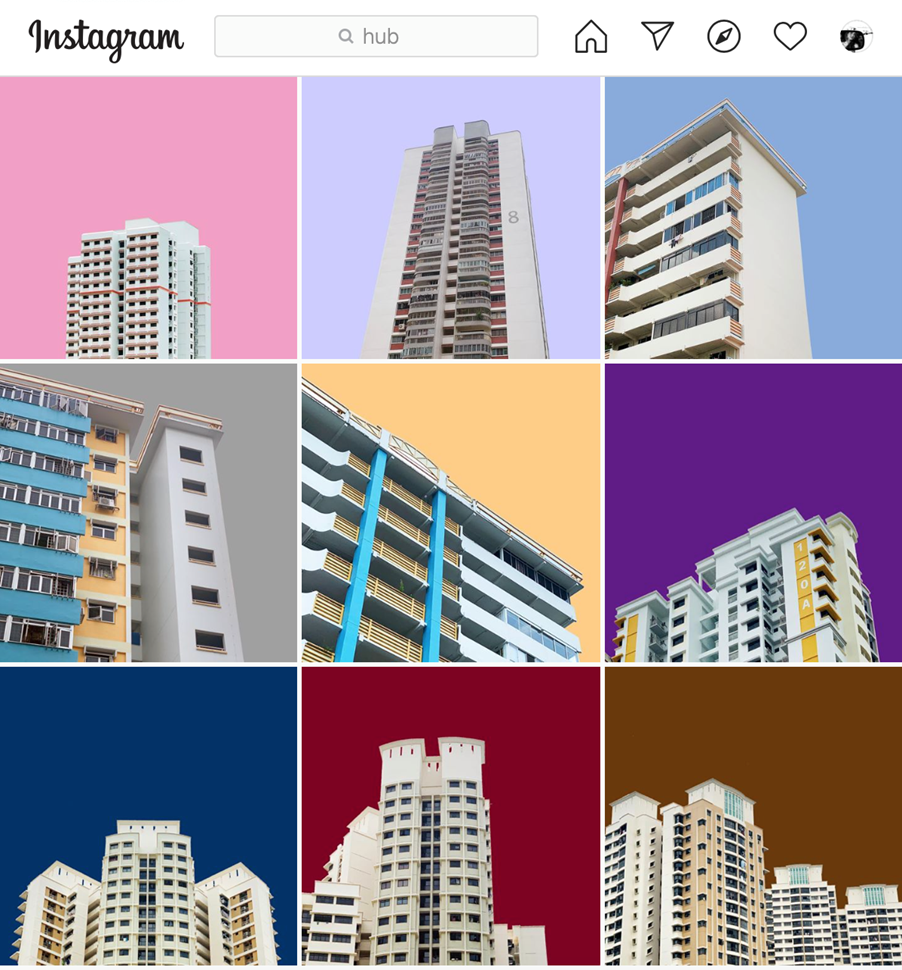

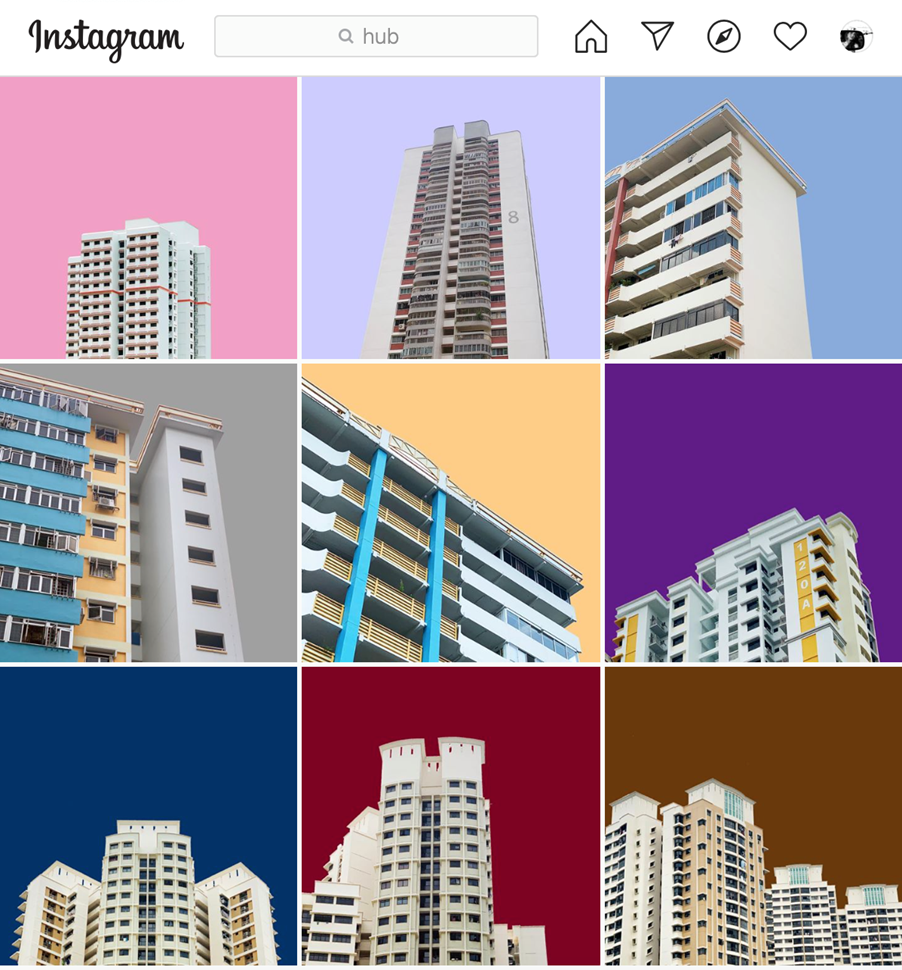

Figure 3. social housing in Singapore Instagram account.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com, 2020

Figure 3. social housing in Singapore Instagram account.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com, 2020

Instagram art

Similarly, the relationship between Instagram and art now includes the dimension of “Instagrammability” as a measure for the audience’s tendency to take pictures and contribute to social media as part of the experience of audiences in museums or art venues. The Victoria and Albert museum has gone from displaying signs prohibiting photography to putting social media at the heart of its plans, encouraging people to share their pictures with specific hashtags. Patrick van Rossem (2016) and Robert Kozinets (2017) agree that the act of taking pictures while visiting a museum and sharing them on social media feeds has to be intended as an individual experience, supporting the construction of personal identities. More specifically,the art of taking pictures and including them in personal social media feeds should be understood in terms of “incorporation” of the art works and the event experience; selfies or pictures allow individuals to weave art and spaces into their own identity [i]. In the case of capturing art, the act of taking pictures can follow an aesthetic pursuit, relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.

The second meaning that museum-related image-based social media feeds have, is to represent subjective or collective interpretations of the space and the collection of the museum. While visitors incorporate the museums’ objects in their identities, they also build the museum’s identity with their pictures [iii]. Visitors re-curate exhibitions outside the physical institution, in online environments, leading to a dynamic re-interpretation of physical and digital spheres. Museum objects that attract the majority of visitors’ pictures usually meet at least one of four criteria: 1) they have narrative relevance; 2) they have a degree of importance; 3) they are iconic; and 4) they are visually attractive [iv]. I argue that, in conjunction with the shareability and scalability of social media,these four criteria create a positive feedback loop for other social media users. Users will adopt the behaviour of the most visible audiences, photograph and re-post similar content, in turn leading to emergent new audiences in the sense of self-organising curatorship.

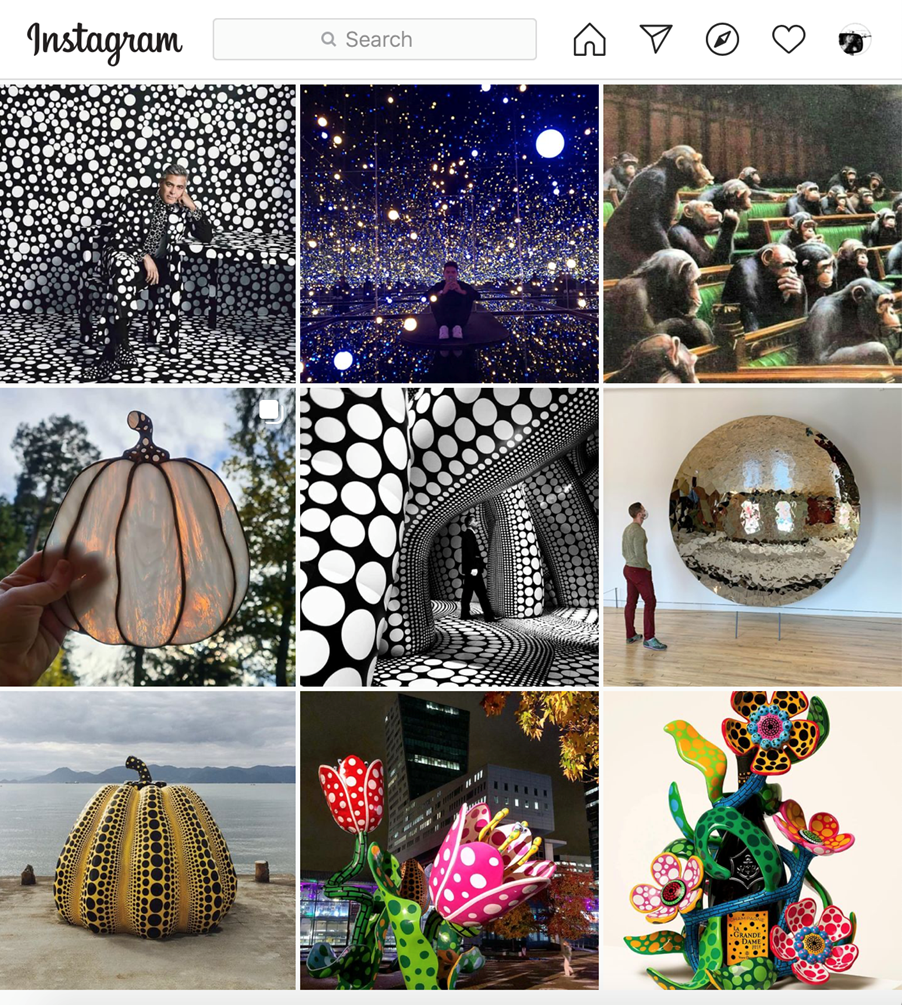

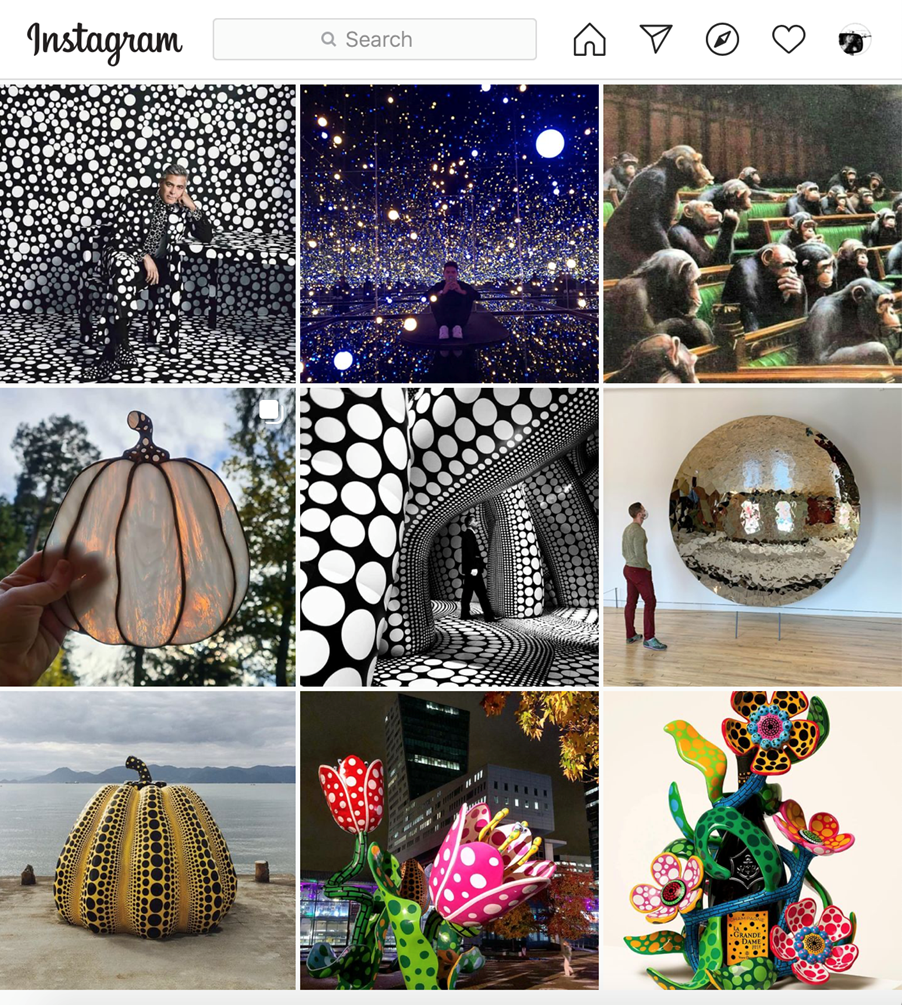

Figure 4. Exhibition of the artist #Kusama in Instagram.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/kusama/, 2020

Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspect of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.

Figure 4. Exhibition of the artist #Kusama in Instagram.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/kusama/, 2020

Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspect of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.

Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspects of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.

Hybrid art spaces

Considering what I observed in the previous section I decided to introduce a new definition to summarise all the previous considerations: Hybrid art spaces.

I define them as such: hybrid art spaces are art venues existing both in physical space and on social media; they result in various forms of hybrid consumption, production, and discussion of art taking place in merged physical and non-physical social spaces.

With this definition, the includes a previous definition by de Souza and Silva, we imply that art production and consumption are social practices [i] that can be situated both in physical spaces and in digital ones. For example, audiences can have access to a piece of art both by going to a museum or by browsing other people's pictures on Instagram. These two art consumption processes are very different, but they reinforce each other and should both be considered in the process of designing an exhibition and in understanding contemporary production and consumption of art.

As presented in this example and based on the observations above, I can summarise different key aspects of hybrid art spaces:

[i] “Selfie Factory,” 2020, https://selfiefactory.co.uk/; Giselle Woon, “A First Look at Singapore’s New Epic Bubble Tea Museum,” 2019, https://www.tripzilla.com/guide-to-bubble-tea-factory-singapore/96813; Sophie Haigney, “The Museums of Instagram,” Online magazine, New Yorker, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-museums-of-instagram.

[ii] Scott Valentine, “Designing Instagrammable: Understanding the Psychology of Instagram,” 2018, https://valearc.com/insight/2017/11/30/0s46178l4r72ewmoqx07irg1ke5g2b.

[iii] Kester Rattenbury and Samantha Hardingham, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown: Learning from Las Vegas, Supercrit, #2 (Abingdon [England] ; New York: Routledge, 2007).

[iv] Alexandra Lange, “It’s Easy to Make Fun of Bjarke Ingels on Instagram,” Dezeen (blog), January 2014, http://www.dezeen.com/2014/01/07/opinion-alexandra-lange-on-how-architects-should-use-social-media/.

[v] Valentine, “Designing Instagrammable: Understanding the Psychology of Instagram.”

[vi] Tom Wilkinson, “The Polemical Snapshot: Architectural Photography in the Age of Social Media,” The Architectural Review, 2015.

[vii] Fabiola Fiocco and Giulia Pistone, “Good Content vs Good Architecture: Where Does ‘Instagrammability’ Take Us?,” Strelka Mag, 2019, https://www.archdaily.com/941351/good-content-vs-good-architecture-where-does-instagrammability-take-us.

[viii] Manovic, Instagram and Contemporary Image.

[ix] Brigitta Zics, “Experiential Art Manifesto,” 2015, https://brigittazics.com/work/experiential-art-manifesto/.

[x] Fiocco and Pistone, “Good Content vs Good Architecture: Where Does ‘Instagrammability’ Take Us?”

[xi] Robert Kozinets, “Netnography: Radical Participative Understanding for a Networked Communications Society,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, by Carla Willig and Wendy Stainton Rogers (1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017), 374–80, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.n22.

[xii] Robert Kozinets, Ulrike Gretzel, and Anja Dinhopl, “Self in Art/Self As Art: Museum Selfies As Identity Work,” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (May 9, 2017), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00731.

[xiii] Rounds, “Doing Identity Work in Museums.”

[xiv] Ellie Miles, “Visitor Photography in the British Museum’s Sutton Hoo and Europe Gallery,” in Museums and Visitor Photography: Redefining the Visitor Experience, ed. Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert (Edinburgh Boston: Museumsetc, 2016).

[xv] Henri Lefebvre and Donald Nicholson-Smith, The Production of Space, Nachdr. (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2011).

HybridArtSpaces uses methods from digital humanities in relation to urban studies to tackle the following questions: Can we learn more about the interrelation of art production and consumption in a new hybrid cyber-physical reality? Can we discern emergent physical spatial clusters from digital usage patterns? Can we postulate a hybrid art spaces in Singapore?

HybridArtSpaces locates art venues such as artist studios, museums, galleries, monuments, and public spaces and juxtaposes these with geo-tagged social media content grabbed from Instagram, Twitter. The findings are interpreted using machine learning techniques described in the research links below.

How to use HybridArtSpaces? This website represents a graphic content explorer for hybrid art spaces in Singapore. Select one or multiple indicators on the right side such as ‘Type of Art’, ‘Use of Space’, ‘Indoor/Outdoor’. Indicators also include processed information derived from machine learning and statistical analysis such as ‘Topic Diversity’ or ‘Sentiment Analysis’. Browse the media content appearing on the left side. Explore the spatial distribution on the map below or filter by venue location.

Have fun exploring the HybridArtSpaces of Singapore here: http://www.hybridartspaces.com!

-

The combination of social media and its capacity for sharing content with peers — in a digital environment through mobile recording devices— creates a special relationship with space and art.

There is an observed trend in disciplines with experiential aspects such as design, exhibition design, architecture, and public space design, the growing tendency to include particular spatial settings that trigger a desire to document and share on visual social networking platforms like Instagram. This feature is commonly referred to using the term “Instagrammable”. The development of this trend is visible in recent exhibitions and art spaces that are only meant to be “Instagrammable” [i]. The trend is also exacerbated by clients, who specify “Instagrammability” in the design brief, especially for commercial projects. This has even prompted Australian architect Scott Valentine to craft an Instagram guide to design [ii]. I will explore the relationship between Instagram and art, and between Instagram and architecture.

Figure 1. selfie factory Instagram account. Source: https://www.instagram.com/selfiefactoryofficial/, 2020

| © Selfie Factory

Figure 1. selfie factory Instagram account. Source: https://www.instagram.com/selfiefactoryofficial/, 2020

| © Selfie Factory

Instagram architecture

There are two phenomena to consider when deconstructing the relationship between architecture or the built environment and Instagram. From one side, people use Instagram while visiting and navigating space as a place for self-expression and communication; on the other side, designers are trying to anticipate social media attention, designing spaces specifically through the lens of Instagram, sometime without fully understanding the phenomenon of how social media and their feedback loops operate.

In order to have their buildings shared in social media, Alexandra Lange (2014) argues that there is an increasing tendency to simplify of the message, to make it fit to the format of the Instagram app and to be viewed in a state of distraction on small mobile screens, with spaces being designed to be understood instantaneously. Therefore, the message has to be immediate, like a ready-made slogan. In this sense, the architecture of the office BIG (Bjarke Ingels Group Office) offers an example: if the form is carrier of a message, the message through the form can be over-simplified, similar to the duck example of famous architect theoreticians of the 20th century Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown [i], with a ready-made slogan symbolically represented in an iconic shape [ii].

The other trend is to address the “Instagrammability” per se, by providing colour and lighting that suit the picture-taking progress. Other specific features, like a selfie wall or physically printed hashtags, might be integrated in the environment [iii]. Tom Wilkinson highlights that the influence of social media has reduced the designer’s role to provide jazzy backdrops and quirky props, flattening the world into a selfie stage set, sometimes impractial as a physical exhibition space in the use of sleek but unsustainable materials [iv]. In doing so, citizens become users that navigate a controlled space in search for a controlled aesthetic, as argued by Fiocco and Pistone (2019): “Even the idea of a city being a collective political project gets easily forgotten in the swamps of neoliberals,as quality of life becomes a commodity for those with money; those who can gain access to the hyper-surveilled, sleek-looking attractions on offer” [v].

In practice, when designing a spatial venue with social media in mind, there might be more than one phenomenon at stake than just the backdrop or the slogan. Rather than designing perfect backdrops, designers should focus on designing environment where people can identify themselves and interact with the space and the social media.

Manovich points out there are three different types of Instagram users, where the majority of them do not seek for a specific polished aesthetics and simply use the social media to document their life and to build up their personal identity though the images [vi]. Considering the general audience that use social media, the attempt to capture physical space and include it in personal social media feeds should be intended as a way to construct personal identities.

In this sense, the features providing the “Instagrammability” of spaces get a different angle of interpretation. To give some examples, one feature that is strongly advised in Valentine’s “Instagrammable” guide is transparency. While Mimi Zeiger suggests that viral trends might follow advances in rendering technology — therefore including transparency in the image, the solution might follow a different logic, with transparency being widely appreciated as it gives the possibility to include the person within the built environment[vii]. Many locations that are highly appreciated by Instagram users, like the social housing in Hong Kong, are considered expressions of the sublime, expressing a strong relationship between emotions and landscape (Figure 2). If considered under those lenses,the “Instagrammability” of places actually pushes for a stronger relationship between spaces and people, while at the same time encouraging people to explore, visit and actually go to places. The trend of people looking out for locations to include in their feeds is a confirmation that places and spaces matter. Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].Architect Farshid Moussavi has a similar opinion: “these environments are not just containers for storing goods or providing services. Instagram is reinforcing the fact that space matters, which can only be good news for designers and architects”[viii].

Figure 2. social housing in Hong Kong Instagram location.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/611757194/choi-hung-estate/, 2020

Figure 2. social housing in Hong Kong Instagram location.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/locations/611757194/choi-hung-estate/, 2020

Figure 3. social housing in Singapore Instagram account.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com, 2020

Figure 3. social housing in Singapore Instagram account.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com, 2020

Instagram art

Similarly, the relationship between Instagram and art now includes the dimension of “Instagrammability” as a measure for the audience’s tendency to take pictures and contribute to social media as part of the experience of audiences in museums or art venues. The Victoria and Albert museum has gone from displaying signs prohibiting photography to putting social media at the heart of its plans, encouraging people to share their pictures with specific hashtags. Patrick van Rossem (2016) and Robert Kozinets (2017) agree that the act of taking pictures while visiting a museum and sharing them on social media feeds has to be intended as an individual experience, supporting the construction of personal identities. More specifically,the art of taking pictures and including them in personal social media feeds should be understood in terms of “incorporation” of the art works and the event experience; selfies or pictures allow individuals to weave art and spaces into their own identity [i]. In the case of capturing art, the act of taking pictures can follow an aesthetic pursuit, relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.relating to the art’s harmonious visual properties or dealing with the art’s concept and message [ii]. Both the visual properties and the art’s concept are incorporated in social media feeds, to enhance self-images of those who utilise them.

The second meaning that museum-related image-based social media feeds have, is to represent subjective or collective interpretations of the space and the collection of the museum. While visitors incorporate the museums’ objects in their identities, they also build the museum’s identity with their pictures [iii]. Visitors re-curate exhibitions outside the physical institution, in online environments, leading to a dynamic re-interpretation of physical and digital spheres. Museum objects that attract the majority of visitors’ pictures usually meet at least one of four criteria: 1) they have narrative relevance; 2) they have a degree of importance; 3) they are iconic; and 4) they are visually attractive [iv]. I argue that, in conjunction with the shareability and scalability of social media,these four criteria create a positive feedback loop for other social media users. Users will adopt the behaviour of the most visible audiences, photograph and re-post similar content, in turn leading to emergent new audiences in the sense of self-organising curatorship.

Figure 4. Exhibition of the artist #Kusama in Instagram.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/kusama/, 2020

Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspect of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.

Figure 4. Exhibition of the artist #Kusama in Instagram.

| Source: https://www.instagram.com/explore/tags/kusama/, 2020

Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspect of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.Social media and Instagram have proven to have a strong impact on the way people are already designing spaces and curating art exhibitions, often reducing the application of social media interaction with space to a frantic search for a simplified, iconic aesthetics. While this might be the current trend, a deep analysis reveals it is only one aspects of people’s interaction with social media in space in general and art venues in particular, and that cultural planners and designers in the sectors may benefit from a deeper analysis and new operative tools.

Hybrid art spaces

Considering what I observed in the previous section I decided to introduce a new definition to summarise all the previous considerations: Hybrid art spaces.

I define them as such: hybrid art spaces are art venues existing both in physical space and on social media; they result in various forms of hybrid consumption, production, and discussion of art taking place in merged physical and non-physical social spaces.

With this definition, the includes a previous definition by de Souza and Silva, we imply that art production and consumption are social practices [i] that can be situated both in physical spaces and in digital ones. For example, audiences can have access to a piece of art both by going to a museum or by browsing other people's pictures on Instagram. These two art consumption processes are very different, but they reinforce each other and should both be considered in the process of designing an exhibition and in understanding contemporary production and consumption of art.

As presented in this example and based on the observations above, I can summarise different key aspects of hybrid art spaces:

- In hybrid art spaces, the idea of production and consumption of art merge and intensify. Audience members re-curate while consuming art and sharing images in their personal feed in an act of value creation. By taking pictures and sharing them, they incorporate the piece of art, creating a new personal artistic expression in an act of art production.

- Social media influence the value creation, by affecting the visibility and the desirability of the piece of art.

- Social media act like a recommendation system, creating a positive feedback loop between the discussion on social practices connected to art and the social practices themselves.

- There are visual and spatial features of the art and the space, which contribute to the positive feedback loop (media creation and attendance of venues) of the hybrid art spaces, determining a hybrid art space’s narrative power and immersive standing.

[i] “Selfie Factory,” 2020, https://selfiefactory.co.uk/; Giselle Woon, “A First Look at Singapore’s New Epic Bubble Tea Museum,” 2019, https://www.tripzilla.com/guide-to-bubble-tea-factory-singapore/96813; Sophie Haigney, “The Museums of Instagram,” Online magazine, New Yorker, 2018, https://www.newyorker.com/culture/culture-desk/the-museums-of-instagram.

[ii] Scott Valentine, “Designing Instagrammable: Understanding the Psychology of Instagram,” 2018, https://valearc.com/insight/2017/11/30/0s46178l4r72ewmoqx07irg1ke5g2b.

[iii] Kester Rattenbury and Samantha Hardingham, Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown: Learning from Las Vegas, Supercrit, #2 (Abingdon [England] ; New York: Routledge, 2007).

[iv] Alexandra Lange, “It’s Easy to Make Fun of Bjarke Ingels on Instagram,” Dezeen (blog), January 2014, http://www.dezeen.com/2014/01/07/opinion-alexandra-lange-on-how-architects-should-use-social-media/.

[v] Valentine, “Designing Instagrammable: Understanding the Psychology of Instagram.”

[vi] Tom Wilkinson, “The Polemical Snapshot: Architectural Photography in the Age of Social Media,” The Architectural Review, 2015.

[vii] Fabiola Fiocco and Giulia Pistone, “Good Content vs Good Architecture: Where Does ‘Instagrammability’ Take Us?,” Strelka Mag, 2019, https://www.archdaily.com/941351/good-content-vs-good-architecture-where-does-instagrammability-take-us.

[viii] Manovic, Instagram and Contemporary Image.

[ix] Brigitta Zics, “Experiential Art Manifesto,” 2015, https://brigittazics.com/work/experiential-art-manifesto/.

[x] Fiocco and Pistone, “Good Content vs Good Architecture: Where Does ‘Instagrammability’ Take Us?”

[xi] Robert Kozinets, “Netnography: Radical Participative Understanding for a Networked Communications Society,” in The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research in Psychology, by Carla Willig and Wendy Stainton Rogers (1 Oliver’s Yard, 55 City Road London EC1Y 1SP: SAGE Publications Ltd, 2017), 374–80, https://doi.org/10.4135/9781526405555.n22.

[xii] Robert Kozinets, Ulrike Gretzel, and Anja Dinhopl, “Self in Art/Self As Art: Museum Selfies As Identity Work,” Frontiers in Psychology 8 (May 9, 2017), https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.00731.

[xiii] Rounds, “Doing Identity Work in Museums.”

[xiv] Ellie Miles, “Visitor Photography in the British Museum’s Sutton Hoo and Europe Gallery,” in Museums and Visitor Photography: Redefining the Visitor Experience, ed. Theopisti Stylianou-Lambert (Edinburgh Boston: Museumsetc, 2016).

[xv] Henri Lefebvre and Donald Nicholson-Smith, The Production of Space, Nachdr. (Malden, Mass.: Blackwell, 2011).