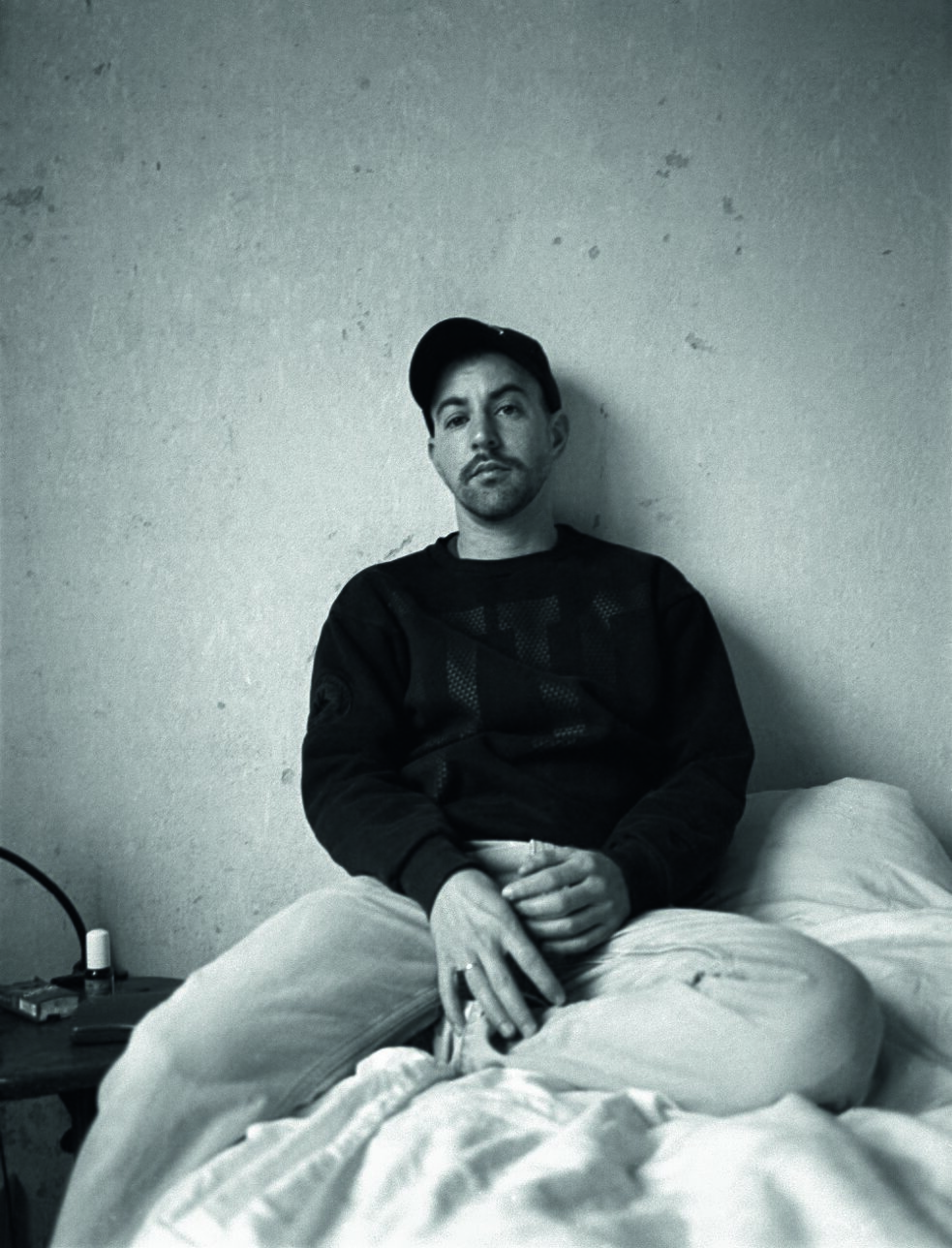

Interview with Tucké Royale

On Daydreams and Just the Right Pen

To grasp all of Tucké Royale’s artistic work, take a deep breath. He’s a film director, musician, activist, actor, author, thinker, teacher, but above all, he’s a mensch. His great creative urge is based on the desire to participate in the transformation of our world into another, better one. At least that’s how I interpret his work, which I honestly only began to examine after seeing "Neubau".

By Sascha Ehlert

Maybe you’ve heard the name Tucké Royale from the Act Out initiative, maybe you’re familiar with the manifesto he wrote for the New Taken-For-Grantedness – maybe not. Either way, the following conversation I had with Tucké via Zoom in December 2020 is an invitation to get to know a very multi-layered artist.

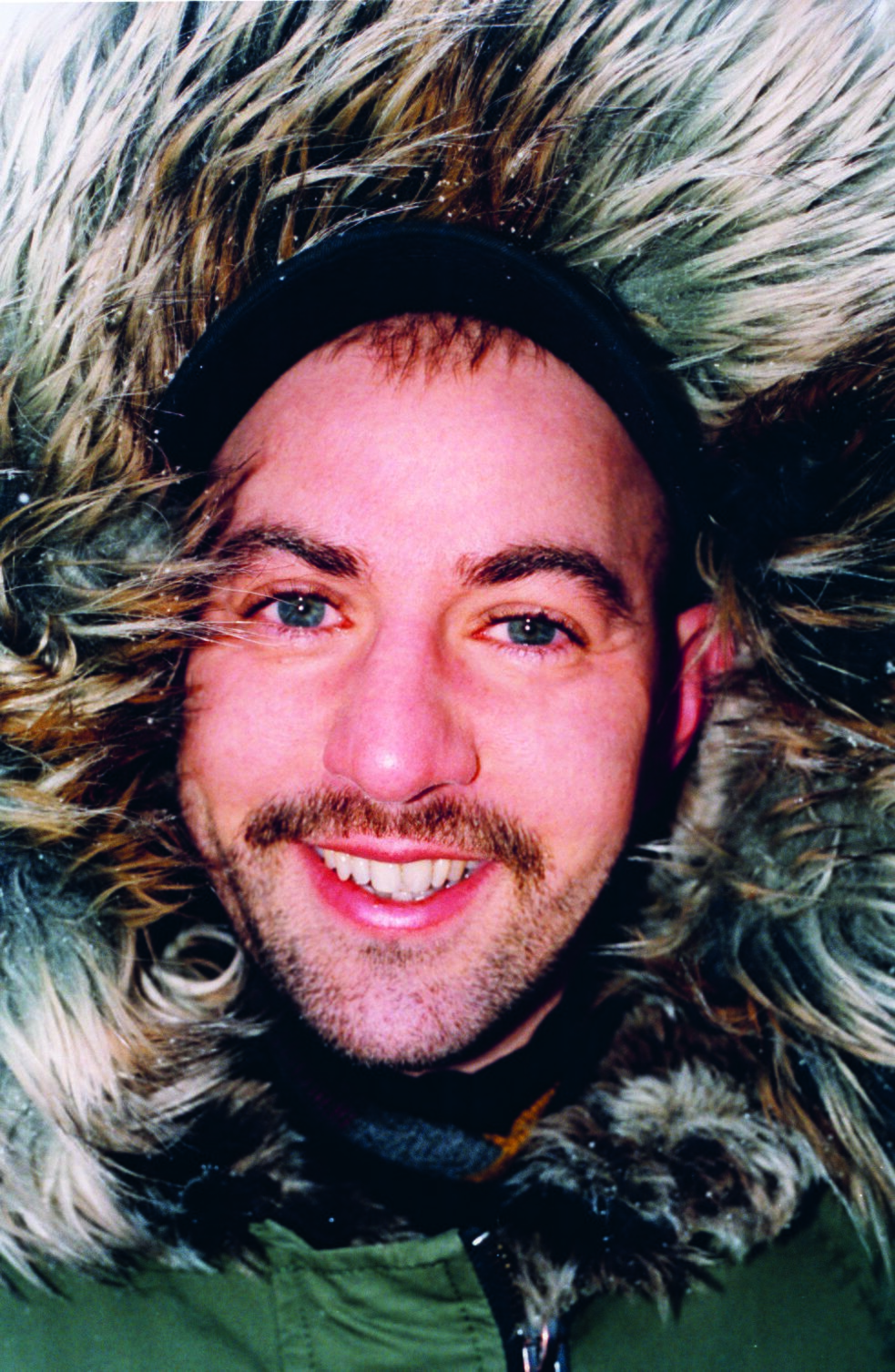

Neubau is a film directed by Johannes Maria Schmit. It actually was meant to have been on the big screens long ago and hopefully still will because Neubau is really big cinema in a very small sense. Tucké wrote the screenplay and also plays the lead. Through his script and his acting, he tells the story of a person on the periphery of Brandenburg. This person loves, lives, doubts, loses, is caring, is thoughtful. All of this is shown in a very reduced, restrained form, in which the focus is on the interpersonal relationships between the characters. The film also tells the story of a queer person who is thinking about leaving home and moving to the big city, but at the same time has people keeping him at home in his small town. But what’s sensational, what’s newsworthy, is not the plot itself, but the tenderness with which Neubau observes young and old people and lets them play. It’s the melancholic, thoughtful calm that this film radiates, which continues to resonate after you’ve seen it.

So far, you’ve only screened "Neubau" a few times on a smaller scale; a setting that’s perhaps not such a bad fit for this film, which, I think, relies on people being willing to let it get close to them. What have people told you about their viewing experiences after being allowed to see Neubau in these almost private settings?

Tucké Royale: Very different things. Last summer, for example, we had a screening in the Uckermark that took place outdoors and followed a long public discussion. There were people from the region – the film was shot in the Uckermark – who thought it was nice to see so much landscape in the film. Then there were tourists at the screening who thought that same thing was somehow dreary or depressing. And there were people who said, “He’s alone all the time and he smokes and drinks so much – is that necessary?” Which is probably a question of viewing habits. Maybe the people who observed that usually watch a different kind of film.

small rural towns aren’t automatically heterosexual

But overall, I had the feeling that the people in the Uckermarck understood Neubau in a similar way to how I see the film myself. I mean the way that Markus, the protagonist, has a very close, perhaps even erotic relationship with the landscape. Interestingly, that’s the thing that people from the city found oppressive, or they even denied this relationship and saw him as isolated. Their thoughts were along the lines of, “This won’t do, he’s got to go to the city.”Sure, that’s of course a widespread judgement in the city: If you’re a person who deviates in any way from the so-called “norm,” you can’t stay in your small town. Was that perhaps one of the reasons you told this story in the first place? Did you want to explore whether the opposite wasn’t also thinkable?

I think so. It was also about appreciating what’s possible in rural areas, what realities also exist there. All the major roles in the film are queer people, which is of course a strong statement and an explicit demand we made on ourselves. Of course, we also wanted to say that small rural towns aren’t automatically heterosexual; and even if they are, they’re not automatically hostile towards queer people. Ultimately, I think that the relationships among people in areas that are relatively sparsely populated are often quite different than in the big city. Willingness to help one another is more important because ultimately, as a community, you can’t afford to do without each other as much.

Of course, in a big city like Berlin, everyone can create their own comfortable bubble. In the countryside, whether you like it or not, you have to get along with your neighbours – even across generations. You also show that in your film.

Yes, of course there’s a certain arrogance on the part of the big city. This is demonstrated, for example, by the discourses that are conducted in the big city – they may often not really be received in the province, which is why city people judge the people there on that basis. But people don’t automatically behave better in the big city just because they are more discursive. And just because you know your way around certain debates doesn’t automatically say anything about how approachable you are. A grandmother like the one you see in the film may not have read Judith Butler, but she can still be a very warm, agile companion.

a gift to ourselves

Would you say that you made this film “for” certain people, or is there a conscious intention behind it? You wrote a manifesto, for example, so it’s probably reasonable to assume that Neubau is also a programmatic film in a way...I think the film points in different directions. On the one hand, it’s a gift to ourselves. To the team that produced it and ultimately to myself. With the screenplay I wrote, I gave myself a role that would never have otherwise been offered to me. At the same time, the film is also a gift for many other people who might be happy to see a film that takes different biographies more for granted and doesn’t play them off against each other. Moreover, behind Neubau there was also a professional longing to be allowed to play a role and to be able to concentrate on acting and camera work. When I wrote the screenplay, I originally had a dedication in it. Ultimately, I decided to remove it because it seemed too personal at the time, but in the end the film is very much dedicated to my late grandmother. I only noticed it in the third draft or so when I was writing it, but I think I’m also getting in touch with her again with the script, or trying to love her again.

When did you write the screenplay?

Shortly before the shoot. We started shooting at the end of June 2019, and I had started writing the screenplay in January. It wasn’t originally planned that I would write the screenplay, but someone else dropped out. Nevertheless, I already had ideas in my head about what story I wanted to tell, so it was easy for me. Between January and May, I produced five versions before I handed in the script.

But you already knew at that point that you would play the protagonist yourself?

Yes, I knew that. That’s why I had to deliberately wear two hats. I wrote the screenplay, handed it in, left it for a few weeks and only then started to learn my part, so I went from being a writer to an actor, did a few rehearsals, role-playing, to find out how this character walks, how he talks, what kind of guy he is. Interestingly, for example, at the time I wrote the screenplay, I had just been a non-smoker for two years and it was only when I was rehearsing that I noticed that my character smokes almost all the time – and then I started smoking again myself. I also had to get my driving licence for the role, because it was already clear that he would be driving a car. And I also give myself a shot in the film – and I couldn’t do that either. I was actually quite scared of doing it myself. But because of these unfamiliar things that I had to learn for the character, it was ultimately easier for me to approach the text in a new way.

I often find great beauty in little things

Is this new working practice, screenwriting, one that has worked for you so well that you want to keep it in the future?Yes, definitely. I already have plans to write another screenplay. However, it’s not yet clear whether I will also act in it myself. I always feel like it, of course, but that’s not my primary motivation to write something.

What role does your "Manifesto for the New Taken-For-Grantedness" actually play for you in writing? Is it a kind of basic rulebook for your screenplay projects?

I do believe that it always plays a role. Of course, I also ask myself how the characters I write can act out of their everyday lives without having to explain themselves to a supposedly ignorant or empathy-less audience. Likewise, on principle, I always ask myself the question: What conflicts actually exist between the characters? In which layers are they? Of course, they don’t always lie at the level of questions about identity, but if they do, then I ask myself how I can portray these people without damaging the characters or retraumatising an audience that’s already vulnerable. Especially with depictions of violence, it’s a big issue for me. For example, I’m also currently working on a novel project that will be set to a large extent in Saxony-Anhalt in the nineties. As regards this project, I’m asking myself how I can describe the neo-Nazi violence and the mobs on the streets that appear in the story without diminishing the threat, but at the same time without handing the Nazis a battle painting.

Regardless of the form and subject matter, what’s your work process? Are you someone who needs to be in the place where the story is set in order to work? Do you do a lot of reading and research?

Both. It usually takes me a year to get comfortable in the material. I often have a basic structure that I hang on the wall and shift about. I basically work in a very structured way and know certain things about a material very early on. Sometimes I dream certain things that then find their way in. For example, in Neubau there’s this Golf with the Fraktur sticker on it – yes, I dreamt that. Nevertheless, I always enjoy being on site. I always have the feeling that sensory experiences in a place are something very specific and I can remember them even at my kitchen table, but only if I’ve been there before. Otherwise, I wouldn’t even think of them. From here, in winter, it’s already hard to remember what that one melted tar crack on the way to the lake looks like. I often find great beauty in these little things. But that always involves intensive research. How intensive it is, of course, always depends on the material. For example, for the book I’m currently writing, I’m dealing a lot with the Treuhand and the chronicles of right-wing extremist attacks. I’m trying to compile that kind of chronicle myself for the city I come from, and I’m writing down what actually happened from day to day. Of course, that’s actually a huge diversion, this quasi-historian’s work and you never really know how much of it will ultimately find its way into the book. Of course, I’m not writing a history book and won’t reproduce it one-to-one. The question for me is instead: What effects do these realities have on my characters? In what way does it play a role in their lives?

Yes, I’m trying to figure that out for myself right now. I always think I have to work “hard” on my material, but then I realise over and over again how much I need to take long walks, daydream, take notes on my mobile phone and get into a rhythm that isn’t interrupted by office work or something. Of course, that’s a luxury and not always possible, but I think that’s my main job in the end: to get into a stream of thoughts. It’s interesting that this happens when I actually take time to get away from my work for a moment and go for a walk. But it’s probably quite the opposite; I should just walk more often. Then, I’ll feel better and write notes. Then comes the part where I can focus on working on the document – of course, I can’t do that in the woods.

How long have you known that you need this daydreaming to work?

I think since puberty. Back then I also wrote – and a lot of that grew out of walks. And out of going to the pub. Which is perhaps also a kind of walk. In the end, I found my way of working, my method, after I finished my studies. Of course, it still changes slightly today. For example, recently, and this is going to sound very touchy, I had a really hard time figuring out how to start writing on my manuscript. For a while, I almost went mad because I couldn’t manage my digital document. Then I realised that I had to write down the notes on paper first, then type them up and revise them from there. After that, I spent a long time mulling over the question of the right pen, which probably sounds even sillier now. I just couldn’t work with a lot of pens. But now I’ve found the right one. I ordered twenty of them.

"Neubau" at the movies

go see the film Neubau as part of our ongoing film series Achtung Film!:

on May 5, 2022 at 7:00 pm at the Cinéma du Parc in Montreal

on May 18, 2022 at 7:00 pm at the Cinéma Cartier in Quebec

(both in original German with French subtitles)

on May 31, 2022 at 7:00 pm at the ByTowne Cinema in Ottawa

(in original German but with English subtitles)