TZUSOO on digital beings and motherhood

Ever since childhood I’ve wanted to be a mother and a full-time artist. But when I started my career, I realized that wasn’t going to work anymore. Which is why I began creating a creature I’d have to take care of.

On the occasion of TZUSOO’s solo exhibition Agarmon Encyclopedia: Leaked Edition (2025, MMCA), we asked the artist about her past, present and future, and took a deep dive into her unique universe.

Reconstructing motherhood

Agarmon is a monster born at the instant of orgasm. As far as I know, the name derives from the Korean word “aga”, meaning “baby”, and “agar”, meaning a gelling agent. Agarmon is often referred to as a “surrogate living being”. How would you define a “living being”? Would you say Agarmon fits the definition?

Agarmon is a living being whose body, made of agar, along with the moss growing on it, forms a shared ecosystem. Even when the body rots and falls apart, the moss keeps growing on it. Does that mean Agarmon has died? Louisa Buck once put it this way: “Decay is a form of rebirth and something positive.” Bacteria take over the rotting body, while the moss spreads its spores and keeps growing on this colony of teeming bacteria. Agarmon is a being in whom life and death coexist.

I did not create Agarmon to find ersatz satisfaction as a mother. Actually, I wanted to keep myself busy looking after Agarmon so as to forget my desire to have children. But he turned out to be so cute! And so sensitive. When you have to constantly regulate the light and humidity and look after him all the time, you really grow to love him.

The only Agarmon to die so far was number two. When I received a photo of him in Germany, I couldn’t even really look at it. My father buried him on Mount Guksabong in Geoje – partly because I’d taken such tender loving care of him. Even the museum curators felt sorry for Agarmon as he rotted away. He seems to have been a special creature that people grew attached to. But the death of an Agarmon cannot be compared to that of a family member. That would be presumptuous.

You explore various aspects of sexuality through the spirits called GAN and TAE: cis-heteronormativity, homosexuality, femininity and disease. What do you seek to express about female sexuality? How would you want female sexuality to be explored?

I want diversity. The term “erotic”, although actually limitless, gets applied to an absurdly small category of things. I don’t find porn erotic. I’m looking to figure out: What do I find erotic? What do women find erotic? In the hope that these things will become part of the infinity of forms of “erotica”.

Space and local salience

The low birth rate is widely discussed as a social problem in Korea. What local significance does your latest work have in this regard?I think this installation addresses a whole bunch of developments in Korean society over the past ten years. This is why it ultimately made it through the demanding selection process, and this is why the public can relate to it and enthusiastically embraces it. I feel like I’ve been going my own way alone for a long time, but the fact that the MMCA Seoul is such a central art venue must count for something.

In the presentation of the MMCA×LG OLED Series, it says, “The MMCA×LG OLED Series exhibits new works by a single artist, selected through recommendation and evaluation by experts from the art world in the Seoul Box, the central space at MMCA’s Seoul branch. The chosen artist’s works are designed to reflect the specific characteristics of the Seoul Box (MMCA).” Why did you design the exhibition the way it is now?

I created a “portal” that invites people in. It’s like a game. The MMCA Seoul, which is 13 meters high in places and open on all sides, is a challenging space for artists. The portal I built there lures people into another world for a while. It also summoned Agarmon and the spirits.

What are the reactions so far to the cis-heteronormativity, explicit eroticism and expressions of sexuality in Agarmon? Was there any difference between the reactions in Germany and Korea, and did that give the work a new or more expansive meaning?

“Explicit eroticism” is your own very personal take. Everyone describes it differently: cute, disgusting, warm-hearted. Despite my initial apprehensions, kids like it too. For them, it’s akin to Pokémon or Digimon. The critic Hyo-sil Yang opined with a cigarette in her mouth, “It’s just too vulgar, I can’t look at it.” Perceptions don’t differ all that much between Germany and Korea, but between personal tastes.

Exhibition at MMCA Seoul Box X LG OLED, TZUSOO, 2025 | © MMCA

The future of creativity

In an earlier interview, you said, “AI is going to take over countless screens in the museums of the future. In this exhibition, I aim to take on AI. [...] AI is just one of many tools for me.” Your works have a certain vitality that can only be produced by a hands-on approach to artistic creation. Why do you think man-made things still attract the public more, despite the rapid pace of AI development these days? And how do you see the future of creativity against this backdrop?I’m glad you asked that. When I said in the interview that I aim to take on AI, it was a spur-of-the-moment remark. In art, there’s actually no such thing as winning or losing. Oddly enough, however, I still felt this ambitious impulse to show that AI “can’t compete with my hands yet”. I ended up making my life hell as a result, because I had six months to create a new work for the exhibition, which involved producing two 8K-resolution videos by hand.

I can’t exactly put my finger on the difference. But in my bouts of hypercreativity and over the course of my many exhibitions, I’ve learned that people notice precisely where a lot of painstaking craftsmanship has gone into something, and then they like it. Even if it sounds a bit esoteric, I believe that when I put my heart and soul into something, people can sense that energy.

For example, I also designed the incubator for this exhibition myself. I spent a lot of time working on the eight heart-shaped piercings hanging on it, which literally involved a lot of handicraft. The piercings are quite simple, there’s nothing remarkable about them. I actually wondered whether anyone would notice them at all. But people can’t take their eyes off them. Which shows me there’s something special about them after all. (What’s not so good is that although it’s actually prohibited to touch them, everyone does anyway...)

I’m fed up with today’s AI. Back in 2022, I still found it interesting. But since Dalle’s Aimy, AIs have figured out which images people like. They’ve become less creative, which is why I haven’t been working with AI at all lately.

Exhibition at MMCA Seoul Box X LG OLED, TZUSOO, 2025 | © MMCA

Every day while putting up the installation, as I rode down the escalator to the MMCA Seoul, I could see the curator Park Deok-seon there frowning, fretting about something. I wondered why it was so important to her for the installation to be a success. Her zeal definitely went beyond the professional responsibilities of her post. And yet I was the artist...

Ultimately, the many people working on the exhibition all had the same goal: to put on a good exhibition. Isn’t that fantastic? None of them made much money off it. For me personally, it was a loss-making venture. So why do they do it? Because they like art. That was not a discovery about myself, to be sure, but I was filled with respect, admiration and affection for the fellow professionals working with me last summer.

Stuttgart, Germany

Word has it you’re currently serving as a visiting professor at the State Academy of Fine Arts in Stuttgart. You once said you went to Germany because you were smitten with German philosophy. Which philosophers did you mean? And which philosophers have influenced your works on femininity, including Agarmon?It’s not about one person’s philosophy. It’s more that the character of modern and contemporary German philosophy on the whole suits me well. It is straightforward and unembellished. Even today, when I read the cultural critiques of Gotthold Ephraim Lessing and Johann Georg Hamann published way back when, I can’t contain my enthusiasm for that war of words expressed in such limpid language. It reminds me of the rap battles on the South Korean TV show Show Me the Money, but the subjects back then were art and philosophy. I’m so jealous! I’d like to do that too.

I can’t point to any specific philosophers whose thinking has directly influenced my work. My works are like my children, born of my personal experience. But my life has been influenced by many books, so in that sense there are countless connections. Interestingly, many of them are German aestheticians like Hannah Arendt, Walter Benjamin, Theodor W. Adorno and Ludwig Wittgenstein (Editor’s note: Wittgenstein is Austrian).

What influence did your life and fine arts studies in Germany have on the subjects and forms of your work and on your aesthetics?

Good question. At exhibitions in Korea, people say my art is German, whereas in Germany it’s said to be Korean. People in the US asked why Aimy looks Asian but speaks English with a German accent. I suppose it’s all mashed up.

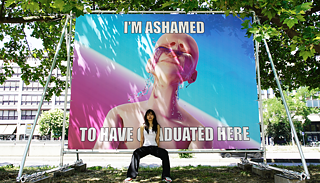

Your final project at the Stuttgart Academy of Fine Arts, I’M ASHAMED TO HAVE GRADUATED HERE (2022), lash out against charging tuition fees of students from non-EU countries. You called attention to that injustice on a billboard and through a sales drive revolving around the €1500 fees. The Aimy avatar, in which you reflected yourself, illustrated your experiences during your art studies as well as systemic problems in Germany. It was an extremely impressive work. Could you elaborate on the situation at the time? How did students, professors and the German public react?

It caused a lot of controversy. Some of the professors said, “Why don’t you compare that to the tuition fees you’d be paying in Korea.” There were comments like “Chinese people study in Germany free of charge, then return home and build ballistic missiles”. Students posted comments online like “A child that wails louder gets more milk” or “You’re keeping those concerned from speaking for themselves”.

That was because I was exempt from tuition fees, so I wasn’t affected. Harping on the fact that some of those showing solidarity aren’t directly concerned is a classic move. But I’d already produced works criticizing this injustice at the beginning of my studies, before I got exempted from having to pay tuition.

I’d moved to Berlin a year before graduating. When I came back to school to get my diploma, it wasn’t an issue anymore, simply because a few years had gone by. But I couldn’t bear the thought of leaving uni with a guilty conscience. So I started planning this project.

Some friends of mine I’d spent five years studying with pitched in. Rebecca Ogle took charge of planning the installation, and the artists Florian Siegert, Shaotong He, Johannes Hugo Stoll and Park Seonha helped set it up. Mona Barmeier handled the red tape required to get permission from town hall. The head of the Baden-Wuerttemberg Kunstverein [art society], Hans D. Christ, unofficially let us use a room in which to cut the tubes and build the framework, and gave us advice and support.

I_M ASHAMED TO HAVE GRADUATED HERE, 2022 | © TZUSOO

Another little anecdote: In the souvenir photo of the graduation ceremony, I was the only one crying my heart out. I love the university and the academy more than anything. I didn’t want to leave. Everyone had to laugh. They asked if it was a performance: my work cried and so did I. Looking back now, that was a difficult time, but it was an apt finale for me.

TZUSOO the artist

You’re often wearing a necktie in photos. Is that a deliberate fashion choice?

I don’t like shopping. I don’t like having to decide what to wear every morning either. In a white shirt and tie, I feel appropriately dressed.

While researching for this interview, I found out that in 2024 you received an email from the MMCA on your birthday, December 3rd, informing you that you were among the three finalists. It also happened to be the day the former South Korean government declared martial law. Back in 2016, I was very impressed by your performance piece The Holy Water Bottle. During the demonstrations against President Park Geun-hye’s government at the time, you served the protesters water from a huge, heavy bottle, which had become a symbol of misogyny in Korean society [because supposedly too heavy for women to lift]. What is your political stance as an artist?

Everything in life is political. Politics isn’t confined to political institutions like parliament or political parties. My art is a means of expressing my thoughts, my feelings, everything that moves me deep down inside. My subject matter is everyday life. I view every scene from my private life from my own perspective – and I stick to that point of view. Misogynistic terms like anyeoja [a pejorative word for “woman”] and sayings like “When you hear the hen outside the wall, the household falls apart” were bandied about even at the protests calling for [the female president’s] impeachment. When I noticed that, I realized I couldn’t be a fully-fledged member of this group anymore.

The Holy Water Bottle, 2016 | © TZUSOO

Because that’s how we all live. We spend so much time mentally engrossed in our smartphones and computers. In the digital world, gender doesn’t matter, and there’s no life or death. And yet we still live in our bodies. When my body is sick, I’m sick too. Gender, life and death still matter a great deal. I tell the story of my generation, which toggles back and forth between these big contradictory worlds hundreds of times a day.

Closing question...Your CV says: “Going to have a child: 2026?” What are your future plans?

I’d like to have a child and I think I could. But that would put an end to my artistic development, for which I work myself to the bone 24 hours a day, and to the management and meagre monthly salaries of the TZUSOO team. Just last night I was complaining about this yet again over some drinks with friends. And I’m always yammering about it to plenty of people at exhibitions and in other situations.

Interview | Shin Sohee, Online PR Goethe-Institut Korea

German Translation | Alexandra Lottje

English Translation | Eric Rosencrantz