YEOJA Mag:

Between Feminist Vision and Reality

“YEOJA” is an online magazine rooted in intersectional feminism, creating space for queer BIPoC communities. In this interview with founder Rae (Mee-Jin) Tilly, we discuss the real challenges faced by independent art, the importance of diversity, and her personal experiences with adoption and migration. Although YEOJA chose to pause in late 2025, its commitment to highlighting those affected by power structures—beyond the category of “woman”—remains as relevant as ever.

Introduction of the Magazine and Beginnings

Could you please introduce your magazine <YEOJA> (@yeoja_mag)?

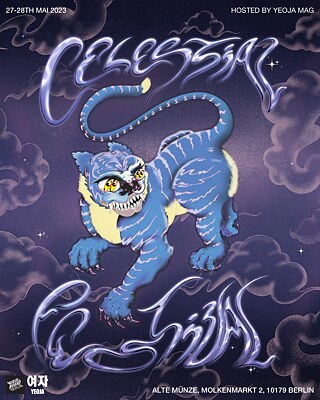

YEOJA Mag is an intersectional feminist platform that exists both online and offline. Our online presence primarily features articles, with a focus on interviews. Our events have included CELESTIAL FESTIVAL, a two-day festival highlighting Asian diasporic communities, as well as workshops like our PASS IT ON series, which is dedicated to sharing knowledge freely. This free structure aims to make access easier for individuals who often face societal and structural barriers.

What inspired you to start this magazine?

I come from the first generation to really grow up with the internet, so my youth was spent discovering it and using it as a way to share my thoughts and connect with others. This started on platforms like Xanga, LiveJournal, Myspace, and Asian Avenue. At that time, there were very few early forms of “internet celebrities.” The internet was mainly a space where you connected with your real-life friends digitally or made connections online with people who became your friends. It wasn’t about going viral or gaining a mass following.

Rae (Mee-Jin) Tilly | © Sarah Tasha Hauber

My personal relationship with the internet adjusted to this new phase, and I also began to share my thoughts with a wider audience. However, over time, I wanted to connect with and share the thoughts of others as well. This coincided with a genuine interest in building community and spaces for people like myself –I was living in Germany, and there wasn’t really a space for expat BIPoC queer folk.

Why did you decide to give the magazine a Korean name?

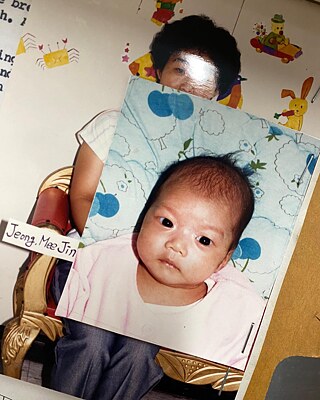

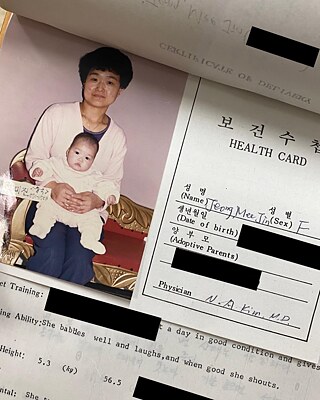

I named the magazine YEOJA because the focus is an intersectional feminist one, markedly different from white feminism. Thus, choosing the word “woman” in a non-Western language made sense. The choice to specifically use Korean is due to my personal and emotional connection – I am a Korean-American adoptee. YEOJA encompasses more than just women and is a publication that focuses on all demographics impacted by systems of power.

What’s your vision for YEOJA and what goals do you hope to achieve?

The goals of YEOJA have always been to build and uplift community, to create, demand, use, and take up space in thoughtful ways, and to create a sustainable structure that would allow me and others who are part of the platform to continue this work. Sadly, for the time being, after a lot of thought, tears, and deliberation, I have come to the conclusion that we do not have the proper resources –external and internal, financial, structural, and more –to carry out these goals. For this reason, it is with a heavy heart that I have placed YEOJA on hiatus until new structures and opportunities become viable.

(Please click here to read our public statement, as well as my personal statement as founder and EiC.)

Artists and Curation

What criteria do you use to select the works of various female artists worldwide that you feature?The main criterion is that the person we platform is part of the BIPOC and/or queer community or occupies other intersections that make visibility in mainstream media difficult. We mainly feature artists in performative spaces (DJs, musicians, singers, dancers, performers) as well as those working in political spaces.

In your opinion, what are the biggest challenges that independent female artists face in their work?

Regardless of gender, I think financial hurdles and industry expectations (such as social media relevancy) can make it really difficult for any artist to thrive these days. Additionally, for those who are politically outspoken, obstacles from institutions or corporate entities can create further barriers. There is a tendency to be louder about the things that impact you directly. Thus, being a woman in the industry often means being outspoken. Every day, garden-variety sexism is also still a very real issue. As in every industry, the higher you climb, the more of a boys’ club it remains.

What kinds of support or opportunities do you think are necessary for artists to make their work accessible to a wider audience?

Work has to be seen in order to be accessible. And for work to be seen, it also has to exist. Creation is only possible under the right conditions. That means people need existential security, time, and emotional space to generate work and to be platformed and amplified.

While I am no expert, my experience with curatorial work for YEOJA, as well as other community projects, is that the people at the top–those with the finances to make things happen–tend to find relevance only in projects they personally deem important. And it often seems that the more privileged a person is, the narrower their view of what is relevant or important.

For a white, cis-hetero male CEO, it is often unimaginable that things outside his personal sphere of knowledge, social scene, and passions could be interesting. And when these things also appear to lack financial incentive–whether perceived or assumed–he is even less inclined to take interest.

While some opportunities are created by well-meaning organizations and institutions to try to level out this systemic inequality, this can also make artists reliant on a singular form of support.

So, unfortunately, I do not have solid answers. But I do believe that getting more diverse people into positions of decision-making power would be a great place to start. It is also a reality that we cannot rely on altruism alone, and the system will not change overnight. So while certain people remain in power and use a different set of criteria to determine what is a worthwhile investment, it is important to think strategically about how to build structures that can hold this in check.

Special Experiences

Is there a project or collaboration within the magazine that has left a particularly lasting impression on you?I was extremely fortunate to co-organize Celestial Festival, a two-day event in Berlin funded by Music Board Berlin, which brought together many people from different creative and political backgrounds, united by the commonality of being part of the larger Asian diaspora. It was a lot of hard work, but an incredibly rewarding experience—one I hope to revive in the future.

The internet allows all of us–individuals, groups, collectives, communities–to have a kind of omnipresence. * Hosting spaces and websites are not entirely free, but they present a significantly lower economic barrier than opening a physical space. It also allows people to connect and engage from all over the world.

However, online content tends to flatten conversations and makes us forget that people are multifaceted beings with quirks and contradictions. It can also create echo chambers. This is why physical spaces are still so important, they allow for face-to-face engagement in real time.

Additionally, the difficulty with online spaces is that we live in a world where people assume internet content should always be free. Thus, it has been incredibly difficult to find any working financial system that allows YEOJA a long-term future outside of relying on volunteers. ** Everyone, including myself, who has worked on YEOJA has done so as a volunteer, with very few exceptions for funding. This funding has primarily been for events, not the online editorial, and is still far from enough–in both regularity and amount–for independent sustainability.

*To a degree, as there are, of course, places where censorship, access to computers, and the internet are still issues.

**While volunteering is an incredible way to support a cause, it is not without its flaws.

Personal Background and Identity

You are active both in Brooklyn and Berlin. What differences have you noticed in the diversity of the art communities in the two cities?Last year, I worked really hard to try to live between Brooklyn and Berlin. However, it wasn’t sustainable in the end for both emotional and financial reasons. Still, I hope to make this work in the future, as Brooklyn is an amazing place full of creativity, openness, and a high level of curiosity. In Brooklyn, and in New York in general, there is a much greater stratification of economic and ethnic backgrounds. No other place I’ve experienced comes close to its level of multicultural diversity in one location. Art communities in Brooklyn (and NYC at large) are also extremely varied–from insanely expensive, highbrow white-cube spaces to incredibly DIY, queer- and BIPOC-led work. While there is some variability here in Berlin too, I think the defining characteristic of the U.S. in general is the level of extreme contrast–both in beautiful and destructive ways.

How has your experience of being adopted from Korea to Germany influenced your personal identity or artistic perspective?

I was adopted to the U.S., not Germany, but I have lived half of my life in Germany, so culturally I see myself as Korean, American, and German. My adoptive family is also Ashkenazi. So being a neurodivergent, queer Korean person–adopted to the U.S. at four months old, raised Jewish, and then moving to Germany–has made for a very interesting mix.

In a perfect world, our personal identity would be shaped by our genuine understanding of who we are, untouched by outward perceptions. However, much of the way we identify is based on interactions with our environment and with others. I have tried my best to put those influences aside while still acknowledging how my surroundings and the people around me have shaped my experiences.

For example, when I went back to Korea three winters ago, I felt at home in the sense that I didn’t have to confront racism from white Westerners on a daily basis. But I was also very much a stranger in the land of my birth because I couldn’t speak the language and wasn’t raised in a Korean household.

What I can say is that, despite all the emotional and mental difficulties, this experience has made me someone who thinks deeply about community and belonging–and someone who will never underestimate how important both are to every person on this planet.

Values and Message

What values or beliefs are particularly important to you regarding your identity and your artistic work?My values center on making decisions and using my voice to express my political and ethical convictions, while also understanding the realities of this world and practicing grace, for myself and for others. I strive to give people the benefit of the doubt and extend grace, but also to set proper boundaries and demand the respect I deserve. I’m also working hard to give myself credit when it’s due. I will never take ownership of something I didn’t do, but I want to own what I have accomplished and not be ashamed to do so.

Based on your personal experience as an adoptee and your encounters with creatives through YEOJA how would you define the term “diversity”?

Diversity is not homogenous; it should be an aggregation of differences where mutual respect and safety are prioritized, and where equitable exchange is at the center.

What is the ultimate goal you want to achieve?

Oh wow, this is a BIG question. At the moment, I just want to figure out how to create some level of sustained happiness, to be proud of who I am and what I’ve accomplished, and to have more confidence in my work and myself.

Will your website remain online during the pause of YEOJA, so readers can still access the existing articles?

The website will remain as a placeholder, and our Instagram will serve as a visual archive of our online presence and event organizing. However, we haven’t fully decided yet whether all, some, or none of the actual articles will remain accessible. While YEOJA still stands for the same values as before, political spaces and community care have evolved so much in recent years that some of our earlier content may no longer resonate with us.

Interview: Sohee Shin

Korean Translation: Young-Rong Choo

German Translation: Alexandra Lottje

Teaser Image:

Moua wears: blue dress and leg warmer from Neksira

Photography: Rae (Mee-Jin) Tilly

Glam: Moua Dimension

Styling: Paula Armas, Moua Dimension, Rae (Mee-Jin) Tilly

Set Design: Daria, Paula Armas

Art Direction: Paula Armas, Daria, Rae (Mee-Jin) Tilly

Production / Set / Tech Assistance: Sara Morscheli, Kate Brown