Yerevan

Conflicting Modernities

Armenian history throughout the 19th and 20th centuries was tightly interconnected with the notion of the PROJECT. Aesthetic, social, and political desires were projected onto the blueprints and construction sites that still today shape the urban face of the Armenian capital of Yerevan. Nurtured since the 18th century by diasporic communities from India to Europe, crystallized on the fault line between the Ottoman and Russian empires, tragically destroyed in the disillusion and death toll of the year 1915, resurrected in the short intermezzo of the Armenian Republic of 1918, pretended to in the colonial frames of the Soviet empire—the unrealized project of a sovereign nation has been the specter of the architectural imaginary, from early Soviet Armenia, to post-Stalinist modernism and its neo-romantic adversaries, and onward to the postmodern collages of the 1980s and the neo-capitalist realism of today.

The achievement of independence in 1918 entailed the search for an architectural language depicting the symbolic order of the new state. Only two years later, Armenia joined the Soviet proposal for creating a new society. But the projections of identity had not been suspended. The contradictions and tensions within these projects marked the entire Soviet Armenian period and intertwine in the urban fabric of Yerevan. A unique story can be read in that fabric, almost without comparison in the 20th century. Alongside, and in opposition to, the modern and modernist zeitgeist, the characters of three conflicting—national—modernities are at work here.

This is a fascinating story full of masterpieces and stylistic ambiguities designed at the intersections between and the counteractions among these modernist projects. It is as if the desire for a new self-defined social order and reality had to cope with the hidden and unfulfilled promises of an architectural imaginary, expressed by conflicting formal languages. Even the critical architects of today speculate about the legacy of these conflicting modernisms and the lost potential of a collective societal organization that is mainly associated with the culture of a modernist past. Therefore, and not only for architects, Yerevan is the Capital of Desires.

Historicism and New National Style

From the early 1920s to the middle of the 1930s, the architectural environment in Armenia was divided between two main circles of architects who possessed diametrically opposite aesthetic, philosophical, and political visions and different approaches to the architecture of the new Soviet republic. Architect Alexander Tamanyan, who is considered the founder of the New Armenian architectural school, proposed a historicist principal where the new architecture would fill the gaps in the historical evolution of the culture and its interrupted statehood.Tamanyan developed and started the realization of the master plan of Yerevan by pinpointing the most important axes and directions of the city’s framework. Government House and the People’s House (now Yerevan Opera House), the two principal buildings designed by Alexander Tamanyan, became models of the new national architectural style demonstrating the compositional, spatial and aesthetic re-interpretations of medieval Armenian ecclesiastical architecture.

Constructing a Social Nation

The circle of architects that confronted the “historicists” propagated a project of radical aesthetic and social renewal. Graduates from VKHUTEIN, Karo Halabyan, Mikael Mazmanyan, Gevorg Kochar, Tiran Erkanyan together with the architects Arsen Aharonyan, Hovik Margaryan, Samvel Safaryan and others that had graduated from the Armenian architectural school founded in 1921, were united in a group called OPRA (Organisation of Proletarian Architects of Armenia). The architects of OPRA not only defended the modernization and rationalization of construction, but also conceptualized and emphasized the importance of social tasks and class affiliation for architecture.By the end of the 1920s, the new school of architecture had become extremely influential in defining the main directions for the development of architecture in the republic. OPRA’s architectural projects were closely bound up with ideas for creating a new socialist mode of life – ideas that were expressed in designs for communal houses, residential districts, palaces of culture, and so on. As for architecture’s national affiliation, members of OPRA defended a concept of a “truly national architecture”, meaning architecture that did not mechanically reproduce forms borrowed from the past, but that derived from social and economic needs.

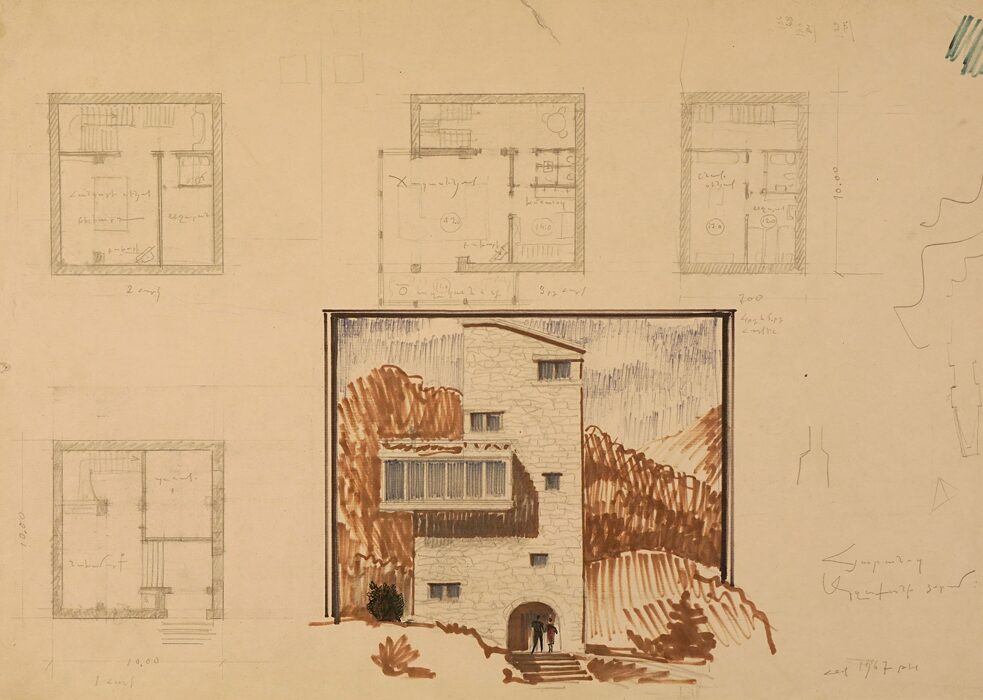

Class oriented architecture was another important premise for these architects, which they also combined with the aspect of the national affiliation of architecture. For them, the only source capable of nourishing “proletarian” architecture was vernacular architecture, with its simple rational forms that suited the specific local social, economic, and contextual conditions, resulting in an architecture that was “proletarian in substance and national in palette”.

The Problem of National - Form and Content

During the second half of the 1960s, historicizing principles that had been taboo in the architecture of the Khrushchev era were reintroduced, but in a new context. Although Tamanyan’s neo-Armenian style continued to be regarded as the basis of the new national architecture, it was actually no longer capable of inspiring the new generation of architects. In reanimating the neo-national style, an important role was played in the themed-1960s by the architect R. Israelyan, who, while employing the stylistic principles of medieval as well as vernacular Armenian architecture, was able to re-examine its aesthetic through a functional-constructivist prism. Israelyan’s aesthetic of modernized structural components drawn from traditional architecture was not only embodied in his architectural designs, but also had a colossal influence on the local architectural approach, shifting its emphasis from a discourse concerning the social function of architecture to a discourse concerning cultural essentialism. In spite of its profound romantic essence, this approach again introduced ambiguity into the architectural situation in Armenia, confronting the socially important functional principle in architecture with the symbolic principle of architectural form creation. On this occasion however, the confrontation was not imposed from above, but occurred within horizontal discourse criticizing the unified approach of both Soviet and modernist architecture.

The influence of neo-national discourse on architectural practice was not comprehensive, but its presence was appreciable in both criticism and theory, and provided the impulse for various creative attempts to synthesize universal modernist approaches with elements of traditional architecture, from structural elements to plastic shapes.