Interview with Lilin

Holding the Knife, Venting the Fire

Editor's Note: The trajectory of artist Lilin, from Dalian to Shanghai, reveals an alternative narrative of diaspora—one defined not by cross-border migration but by deliberate movement and self-reinvention within China’s urban landscape. Transitioning from bookstore owner to printmaker and ceramicist, she employs “venting the fire” as a creative impetus, transforming anger and uncertainty into tangible artistic action. At a time when physical spaces are diminishing and human connections are transforming dramatically, her practice explores how even the most basic networks of acquaintances can restore a sense of proximity and create meaningful encounters within the anonymous expanse of the city. Her story raises a universal question: When former modes of life and work become untenable, how does one seek out new tools and spaces—and, in the process, rediscover where one belongs?

By Lilin; Yun Chen

From Echo Bookstore to Agency Studio

CY: Could you start by talking about your experience in Dalian—with Echo Bookstore [回声书店]—and how things shifted afterward?LL: I first tried printmaking in December 2019. By then, it had already been over two years since I closed Echo Bookstore, which I’d run for nine years. I was then working with Sun Wei on a space we called Agency Studio [主动工作室] here in Dalian.

After closing the bookstore, I went through a period with not much to do. I still had some books left, so I asked on social media whether anyone could offer an indoor space where I could donate them—somewhere people could come and read freely. But no one responded. I couldn’t find a single open space that was both accessible and in need of books.

The announcement about closing Echo Bookstore got over 60,000 views. In it, I’d mentioned that if anyone could offer a (semi-)public space for the books, they should contact me. Yet even with that many readers, not one person got in touch. It felt like society was telling me it simply didn’t need books anymore. In a way, that explained why I closed the store: books were no longer a real need. I realized I couldn’t keep doing something book related.

That said, what I loved most about the bookstore was organizing events—over those nine years, I held screenings, staged exhibitions, and invited many writers. Because Dalian didn’t have a very large local creative community, bringing people in from elsewhere created opportunities for interaction and connection. That was what made it meaningful. Just the other day, I ran into Zhao Song, and he still remembers that I once invited a teacher from Shenyang, Ren Haiding, to dialogue with him. They became good friends afterward. Making those kinds of encounters happen was really fun.

After losing a physical space, I did regain a certain freedom—I could organize events in other places. For a while, I enthusiastically sought out little bars and cafes across Dalian where I could host screenings. Relying on the goodwill I’d built through Echo, I’d hold one event here, another there … just making things happen anywhere I could.

That eventually led to the idea of a studio. Sun Wei and I felt people still wanted a place where they could just sit and be together. He knows every corner of Dalian—he found this old colonial-era building downtown that had served as senior staff housing during the Japanese occupation. The structure was elegant, yet it had slowly decayed over the space of a hundred years. Inside, there was this breathtaking spiral staircase, dust draping the handrail like a veil … as though no one had touched it in a century.

Our room was on the fourth floor. You’d open the door and step into this clean, renovated space—it felt like stepping through time. It was about the same size as Swimming Office (the open studio I later had in Shanghai), with two small rooms and even a tiny living area. Compact, but cozy. We spent another stretch of time there together.

Printmaking: Action and Anger as Creative Methods

CY: How did printmaking become a new tool for you?LL: The moment I tried printmaking, I found it incredibly intuitive and intensely satisfying. I felt it myself, and then I became eager to see that same expression on other people’s faces—that irrepressible joy. Every time someone pulled their first print, I’d quickly grab my phone, wanting to capture that genuine look of surprise when they saw their image transferred for the very first time.

Since I’d had very little experience producing images before, the sense of empowerment printmaking gave me was profound. This simple set of tools really allows people with no background in image making to discover, as soon as they finish a piece, their innate potential to speak through visuals.

For me, from the very beginning, printmaking was a tool for engaging in joint creative activity. It extended the conversation after film screenings and became a new way to deepen connections. I brought it into workshops where we’d carve prints inspired by films, then assemble them into posters—I even sold some online and shared the revenue. This added another layer to the relationships among everyone involved. Printmaking is direct and clear. Many friends discovered the energy of materials through it.

I kept making more prints, but I stuck to my original approach: I wasn’t making images for the sake of images. If I thought that way, I’d get trapped by the image itself and wouldn’t be able to act. Precisely because I wasn’t focused on the image from the start—what I was really doing was communicating and activating—the images became happy by-products. They could be anything; they emerged naturally. Even now, printmaking remains a communication tool for me, a way to create long, engaged moments of shared action. That became my method.

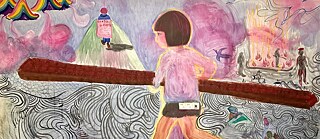

What truly turned printmaking into a personal creative catalyst was joining the translation project Working Class History: Everyday Acts of Resistance & Rebellion, initiated by Chen Yun. I translated the entry for September 14, which talked about Patrice Lumumba, the first elected prime minister of the Congo. That short text impelled me to look up more—I saw his photos, learned about his life, and I got furious. That’s when I discovered my next method: if my first method was “action,” my next was “anger.”

I was so enraged, and felt so powerless, that a carving knife appeared in my hand. My work wasn’t born from the act of designing an image—it was a venting of the fire I felt inside. In that process, I reacted intensely, without any illusion of creating a masterpiece. It bypassed thinking and went straight into action, full of unexpected surprises. That’s exactly what felt so liberating about printmaking.

That book totally activated my printmaking output. After carving Lumumba, I felt I could do more. When I got the English copy, I felt purpose. Every morning, I’d open the book and read. If an entry made me angry, I’d dig deeper. The one that infuriated me the most became that day’s work—I’d carve it. Many prints were made through angry, tearful carving.

I had almost no image-making experience before, but starting like this felt completely right. I had no doubt—they were exactly as they should be. I just wanted these stories and voices to be visible again, to be heard one more time. Whether people liked them or not wasn’t important. The fact that I could transform this anger into something else filled me with joy. It was perfect.

Arriving in Shanghai by Way of Printmaking

CY: What led to your decision to leave Dalian for Shanghai?LL: I could feel that there were fewer and fewer things I could do in Dalian. The economy in Northeast China was declining, the energy among young people felt low, and organizing events became increasingly difficult. Staying in a place where I could literally see the possibilities shrinking around me started to feel suffocating. I knew I needed to move somewhere else to reignite myself.

I had already decided to leave in 2019, but the question remained: Where to, and how? After so many years in Dalian, my roots had grown deep—pulling myself out would take effort. I thought I should start by building connections elsewhere, like a plant sending out its roots, testing whether they could take hold in new soil.

After the bookstore closed, I really went through a stuck period. I felt drained, completely depleted. But I still had this powerful urge to work—I wanted to find a new way of working. My most familiar tool had always been words, but when I tried writing, it felt painful. So I kept searching for other possibilities. I traveled to Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou to meet friends. Without fully realizing it, I was looking for a tool I could actually work with—and printmaking became that gateway.

It was printmaking and the Working-Class History project that connected me to Shanghai. In a way, I followed printmaking here. I finally moved in June 2021. Even though I was only here for two and a half years, it felt like five—COVID lockdowns, relationships with neighbors, intense interactions … all of it made me familiar with the city very quickly.

During lockdown, in particular, carving rubber stamps every day saved my mental health. Many friends I made in Shanghai became “comrades in hardship”; we went through those times together as allies. Those shared experiences created deep emotional bonds.

Building a “Soft Network” of Proximity

CY: How would you describe the life and work network you built in Shanghai?LL: In Shanghai, I started Swimming Office [游泳办事处]. There, I hosted a steady flow of old and new friends who came to make prints. If I have one regret, it’s that I might not have made the most of what Swimming Office could have been. Toward the end, I was indeed hosting very few public events—it became more about friends, and friends of friends. In fact, Swimming Office was only in that location for a year and three months. I suppose I’ve always had this stubborn idea about what a “public event” should be. But now I see that a realistic starting point might simply be acquaintances connecting with acquaintances—it’s a way for people to move toward creating a public sphere and building something communal.

The kind of society I want to live in is one made up of people living around each other—some are close friends, some are half-familiar, some are strangers whose faces you recognize and who still feel relevant to your daily life. It’s a society where you can walk down the street and run into plenty of people you want to say hello to. The Shanghai I’m about to leave is actually a place I’ve felt deeply comfortable in.

I made many friends in my alley. The household directly across from my kitchen window—close enough that we could hear each other knocking—belongs to a friend with many mutual connections. There’s also a friend living in the next building, someone I actually knew through a friend back in Dalian. Everyone in the alley knows each other, and I’ve become familiar with people on several of the surrounding streets.

It’s a messy, overlapping network—not a closed circle where everyone knows everyone else, but a soft layering of spaces that sometimes intersect and sometimes don’t. The flower shop across from my alley is run by another neighbor—I bought this little plant there, and I want to say goodbye before I leave.

And remember that time you came over and saw that pitiful little kitten on your way out? Another neighbor and I worked together to rescue it. She had just moved from Beijing, and we clicked immediately—though we never found more time to talk.

On my walks from home to the studio, I often run into Lu Yi and his family. At another corner, I’d bump into Old Lu, the designer of the Working-Class History calendar. We’re all neighbors. During the two-month lockdown in Shanghai, I even shared some Coke I managed to group-order with them.

A few steps away is Lazybones Home [懒汉之家], and a bit further on you’ll find Lucida Books [明室] and Open Close Open Books [开闭开书店]. We aren’t friends who see each other every day, but we know each other, we know roughly what everyone is doing. We’re connected in a way that feels light, almost effortless—yet if something happens to one of them, I’ll likely hear about it from someone else when we meet.

It’s a soft, comfortable network. It’s exactly the kind of Shanghai I wanted to be part of. This kind of feeling is becoming rare these days—it depends on an environment that hasn’t been torn apart by redevelopment, a place where life can still be shared.

From Printmaking to Ceramics: Still “Holding the Knife”

CY: What led you to transition from printmaking to ceramics?LL: At first, printmaking felt very direct, but over time I began to sense a kind of self-imposed restraint—it wasn’t allowing me to freely vent my anger anymore. I needed a new material.

Last October, after going through something particularly difficult, I went to Jingdezhen. The moment I touched the clay, it felt right in my hands. I don’t make functional vessels at all—only small sculptural pieces, many of which are reinterpretations of images I first made as prints. The process felt just as smooth and satisfying, but freer.

I actually come from a science background—my thinking is pretty bound by logic, full of frameworks. That’s why writing felt so painful: using my hyper-logical brain for creative verbal output was a struggle, like fighting with myself. But when I surrender the creative process entirely to my hands, my brain hardly gets involved. It becomes automatic, intuitive. I realized I could let my mind rest and still vent the fire.

My ceramic sketches are very simple, really rough. I quickly draw lots of little drafts—images I’ve carved before, or new ones that stir that fire inside me. When I lay those small sketches out in front of me, the one that makes me angriest seems to jump out and say, “Me, pick me!” Haha. Then I sculpt it—it’s so satisfying. I naturally developed my own method that way.

I don’t think about color while I’m working. After shaping, I bisque-fire them, and only then do I add color. So my worktable ends up covered with these little bisque-fired forms. And the one that triggered me the most will definitely speak up: “Color me now!” Haha.

Lately, I’ve even been carving some clay pieces with woodcut tools—it’s a new method I’ve been developing that feels amazing. It totally combines everything I love. I don’t enjoy throwing on the wheel, but I carve cups as if sculpting wood—gouging them out from solid blocks.Bringing together woodcut and clay feels incredibly fluid. Ceramics are definitely my next medium.

Not Breaking Away, but Flowing On

CY: When you decided to leave Shanghai, did you feel like there was unfinished business? How do you see this ongoing movement between places?LL: In the weeks before I left, the intense emotional exchanges brought on by goodbyes made me both incredibly happy and deeply sad. I did ask myself: Could I have done more? Did I leave too soon?

But I believe that what remains unfinished can always be continued later. Nothing really concludes the way we imagine it will—what matters is adjusting along the way.

I haven’t truly left Dalian or Shanghai. What I want is to connect them—Dalian, Shanghai, Hong Kong—by showing up in person, seeing friends, and maintaining those bonds. This kind of movement isn’t a rupture—it’s an expansion. It comes from a desire for possibility, and from consciously placing myself in new contexts where I can feel stimulated all over again.