Photography and Ethics

Always New Questions

What can you show? – This fundamental ethical question employs photography, since technical reproduction processes have made the mass distribution of photos possible. Social taboos, artistic freedom and the will of journalistic documentation will are essential elements of an always new discussion.

It was above all the technical aspects that determined the debate about photography, which first made its public appearance in 1839. The question was not “What may or may not photography do?” in the sense of an ethics of the new imaging process; the question was “What can the medium do and what will it be capable of doing in future?”

Only with the invention of the halftone process as printing method (1882), and as a result the advent of the illustrated mass press, was reflection mobilized on the ethical limits of a technology that had long assumed an industrial dimension. And only with the mass publicized image and its mass reception did the discussion begin about the ethical limits of photography. The debate about an author in photography, which was not a purely automatic and thus objective process but had quite a subjective side, an author who in case of doubt was responsible if the limits of the ethical were transgressed, had been decided long before.

That these ethical limits were and are fluid and relative to the culture, time and subject is obvious. When in 1898 Max Priester and Willy Wilcke, photgraphs from Hamburg, took unauthorized photographs of the just deceased Otto von Bismarck on his deathbed, they provoked a scandal, were indicted and the pictures confiscated. Some fifty years later the Frankfurter Illustrierte published a page-size reproduction of one of the photographs – without arousing offence. Especially unauthorized photographs of deceased, war and accident victims, nudes and erotic motifs heated and still heat up the debate.

If in the 1970s the British photograph David Hamilton could still exploit commercially his soft colour shots of scantily clad child-women, today, in view of the debates about child nudity and pedophilia, he would have his difficulties. What in the 1980s met at most with reproof, is now a matter for the law – such as Irina Ionesco’s staged child nude photos or Jock Sturges’s beach scenes, showing denuded women and girls. Paedophilia is the moral taboo of our times and even the suspicion of it is not without consequences.

Pain threshold

Where does artistic freedom end, and where does blasphemy begin? To what extent may the artist provoke without injuring the religious feelings of his devout contemporaries? Questions that the Italian advertising man Oliviero Toscani had to face in the 1980s with his campaign for the clothing company Benetton. Photos, showing for for example a dying AIDS patient or the bloodstained clothes of a fallen soldier, led to social debates about the ethical boundaries of advertising photography. The American artist Andres Serrano had a similar experience: his work provocatively entitled Piss Christ shows a crucifix in a jar filled with urine. This photograph inflamed feelings in the United States at the end of the 1990s.Against the backdrop of a vague ethics of photo journalism, press images in particular are selectively criticized as aestheticizing misery or exaggerating to the point of shock: did the American photograph Todd Maisel have to show the torn-off hand of a victim in close-up and in colour in order to reproduce adequately the nightmare of 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center in New York City? Was this the transgression of a pain threshold, or is it the task of the press to make known a catastrophe in such a drastic fashion? Differently stated, an ethics of photography affects the communication as well as the production of images. May we, should we, must we pass on the current horror images released by the ISIS? Or by doing so do we make ourselves an extended “press office” of international terrorism?

Regarding the Pain of Others was the title of one of Susan Sontag’s last books. In it lies the realization that looking can create empathy, but just as well lead to sheer voyeurism. The primary task of news images is to inform the public of current events. In the long term, they form the foundation for remembrance. What about photographs such as those of the war reporters like the American Margaret Bourke-White America and the Briton George Rodger that show the inmates of liberated concentration camps? An indecent exhibition of the victims? Evidence for genocide? Or an indispensable part of a sustained remembrance through images?

Staging and image manipulation

“Tasteless” is what one could call the photograph made by David E. Scherman in April 1945 of the naked Lee Miller in Adolf Hitler’s bathtub, taken in April 1945 in Munich, shortly after Hitler’s suicide. Moreover, a staged picture that again touches on the broad issue of manipulated images or those put into a questionable context. For various reasons pictures have always been faked. Joseph Stalin’s henchmen were particularly adept in their retouching, their obliteration by means of scissors, brush and pencil. They retouched individuals who hat become unpopular from historically important images to remove these people from public awareness.In the digital age, the so-called photoshopping offers hitherto undreamt-of possibilities, ranging from simple image processing to resolute computer-based image manipulation. The photographic image has lost its credibility. The negative too is now missing as a reference. It seems that even the prestigious World Press Photo Award can no longer forgo “digital forensics” – too great is the temptation, for example, to strengthen their impact. Professional journalists associations such as Freelens have called for a new ethics of image making to restore confidence in photo journalism: No subsequent additions or erasures of image content, no deliberate manipulation.

Personal rights in the global community

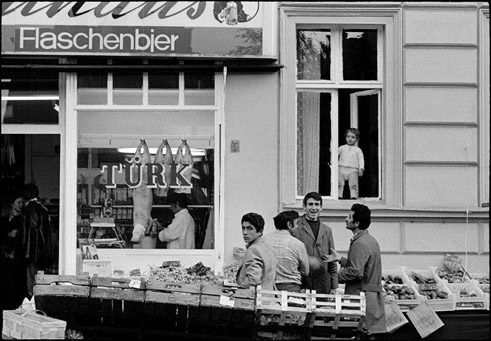

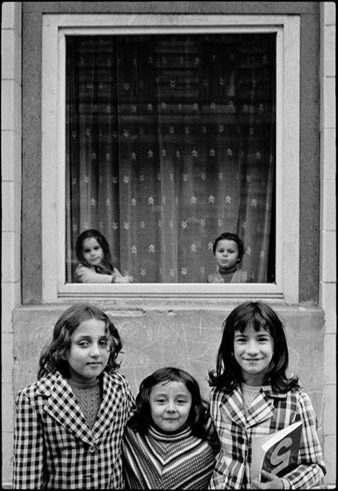

Artistically active photographers, on the other hand, are increasingly disturbed by restrictively wielded personal rights that may well put an end to the genre of street photography. The famous photograph "Rue Mouffetard" by the French photographer and Magnum co-founder Henri Cartier-Bresson from 1954, with its unauthorized portrait of a minor carrying alcohol, would today be the concern of the law.Yet more people take photographs in public space than ever before. Self-proclaimed “photo reporters” put their work on the Net and so reach a global community. What counts is range and speed, not good taste or even “morality”. So much appears to be certain: a fixed ethics for photography, a morally founded and generally accepted code of conduct, does not exist. Depending on circumstances, genre and intention, there are at most always new questions. And the certainty that in the digital age, with its infinite availability of images, the issue of ethics has become only more explosive.

People in everyday situations: in the street, at work, in moments of leisure. It seems as if Ulrich Weichert has his camera with him always. With subtle humour and in seemingly unspectacular motifs, the black-and-white photographs reveal the often absurd scenes of our life. Weichert, who was born in 1949 in Tübingen, was the winner of the 1980 Photokina Prize. Until 2013 he was head of imaging editing at the Federal Press Office.

The Bamberg Historical Museum is showing the exhibition Italy! Italy? Italy. Photographs by Ulrich Weichert until 1 November 2015.