A space for ideas:

How young creatives are rethinking Bauhaus

Would you briefly introduce the Young Bauhaus project and the team behind it: What prompted you to start up the project? And who is it for – who can join in?

Young Bauhaus is a group of young people who meet up at the Bauhaus Archive / Museum of Design in Berlin to create art together and put on their own exhibitions. We’re the organizing team behind the project: two staffers at the Bauhaus Archive – Lisa (Consultant for Inclusion and Diversity) and Sonja (a volunteer in the Directorate and Education Department – along with Sophia and Jorna, two FSJ volunteers at the museum since September 2024.

FSJ, which stands for Freiwilliges Soziales Jahr (Kultur) [literally, “Voluntary Year of Social Service (in the Cultural Sector)”] is a German gap year programme for young people to work as volunteers in the cultural sector for twelve months after high school and get a taste of the working world before pursuing higher education or a career.

Three years ago, we asked the FSJ volunteers on our team at the time: What interests young people about the Bauhaus? What does the Bauhaus need to offer to get you involved in the museum? Their answer was clear-cut: space, materials and a say in what we do here. This led to the creation of Young Bauhaus, a participatory project that gives visibility to young people’s perspectives in our programme.

Since then, we’ve put on two exhibitions of their artworks – both of which were a big success. Young Bauhaus is for any young people who want to participate creatively – free of charge and with no prior experience required. Anyone who wants to join in on a regular basis is welcome to!

You meet up regularly at the Temporary Bauhaus Archive in Berlin. What goes on at a typical meetup? Is there a core group of participants? How do you plan your group sessions and activities? And how important is the Temporary Bauhaus Archive space for your work?

Our group meets up every Wednesday evening at the Temporary Bauhaus Archive. This weekly exchange forms the core of our collective project. The meetups are jointly organized by our four-person team and usually consist of two parts: one part about content – such as planning our exhibition design or presenting our ideas for artworks – and a creative part in which we work together artistically. We paint canvases, build miniature replicas of famous Bauhaus chairs, put tattoos on lemons or try doing exercises drawn from the historical Bauhaus Vorkurs [first-semester preliminary course].

Every year, Young Bauhaus starts in on a new term with the arrival of the new FSJ volunteers and new participants. Some have been with us for some time, even as long as three years. After a few open introductory sessions, a core group of ten to fifteen people usually forms up.

Our space in the Temporary Bauhaus Archive is more than just a place for us to get together: it’s an open, protected space in which creative processes and personal conversations can take place side by side and people can simply feel comfortable. This is where we work together in a laid-back atmosphere, sharing thoughts and ideas and learning from one another. Spaces like this have become few and far between in everyday life, which is why this place means so much to us.

Experimental, open and collective.

You stress that you’re not out to revive the historical Bauhaus. And yet, you must draw some inspiration from guiding ideas, subjects or themes espoused by those who studied in Weimar, Dessau or Berlin back in the day. What are they – and where are you consciously breaking new ground?

“The Bauhaus was a school.” This is the guiding principle of our educational work at the museum. We see it as the starting point for our efforts. We regard the school as a locus of experimentation, learning and self-discovery. We’re particularly inspired by the Bauhaus Vorkurs – a revolutionary educational concept at the time, introduced by teachers like Johannes Itten and developed by László Moholy-Nagy and Josef Albers. All the Bauhaus students went through this preliminary first-year course before specializing in various workshops. This is where they learned the basics, experimented with materials, initiated creative processes and explored their own design skills – all of which remain key aspects of our work at the Young Bauhaus.

But we do deliberately go one step further: Our participants decide for themselves the subjects and issues they wish to address and the materials they want to work with. There are no teachers, just a creative community in which everyone is on an equal footing. Exercises drawn from the Bauhaus preliminary course serve more as inspiration than as directions. We’re more about self-determination than guidelines or templates: Each person is taken seriously as an artist and contributes their own perspectives.

Over the past three years, despite the hundred years that separate us from the historical Bauhaus, we’ve been addressing questions that are remarkably close to those asked by students in Weimar, Dessau and Berlin back in the day. Because the questions young people face are timeless: Should I move out? What should I do next? Who am I really? Who was I before and who do I want to be? How do I want to shape the future of my world? Questions about identity, the future, personal development and challenges to society are just as current today as they were back then. Our approach is informed by the here and now: young, political, individual and, at the same time, collective.

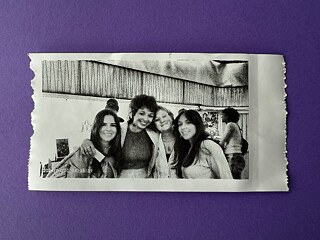

![(left) © Carl Schlemmer (photo): Teachers and students of the Bauhaus Weimar and guests at a party, around 1922, [new print], Bauhaus Archive Berlin; (right) The Young Bauhaus Team 2024, © Erika Babatz (left) © Carl Schlemmer (photo): Teachers and students of the Bauhaus Weimar and guests at a party, around 1922, [new print], Bauhaus Archive Berlin; (right) The Young Bauhaus Team 2024, © Erika Babatz](/resources/files/png187/damsls_heute_yb-formatkey-png-w320m.png)

(left) © Carl Schlemmer (photo): Teachers and students of the Bauhaus Weimar and guests at a party, around 1922, [new print], Bauhaus Archive Berlin; (right) The Young Bauhaus Team 2024, © Erika Babatz

The ideas pursued at the Bauhaus were never written in stone. On the contrary: even during its brief existence, the Bauhaus was constantly changing. Each director set their own priorities, and this openness is precisely what keeps the Bauhaus relatable and adaptable to this day.

For us, the concepts developed at the Bauhaus are not a fixed set of rules, but an open space for utopian thought – a place to try out new things. The people at the Bauhaus were courageous in many ways; They broke new ground and were often criticized for that. Combining art with craftsmanship was just as unusual in those days as admitting women to higher education. Both are a matter of course in our day.

We find it exciting to consider what might be courageous approaches nowadays: showing works at museums by young people who don’t have traditional careers in art, for instance? An experimental approach means mustering the courage to try out new ways of actively shaping the future – the goal being for our conceptions of art and social cohesion to become a matter of course someday.

Here in Korea, it’s hard to find literature that takes a critical and nuanced view of the Bauhaus. How do you view the current discourse in Germany, especially at universities and museums? Are issues like gender equality, diversity and power structures at the historical Bauhaus openly discussed there? Are you, as young artists, included in these conversations?

A critical examination of the Bauhaus has been ongoing in Germany for some time now. Time and again, this “demystification of the Bauhaus” has shed light on various aspects of the school. One current case in point revolves around the phenomenon that after World War II, the Bauhaus was glorified as having been thoroughly progressive, with a focus on stories of exile and “modern” aesthetics. While many members of the Bauhaus were forced into exile or persecuted and murdered by the Nazi regime, some actually benefited from the situation and worked for the Nazi Party after their studies. Our colleagues in Weimar delved deeply into this anomaly in last year’s “Bauhaus and National Socialism” exhibition.

The narrative that the Bauhaus was progressive because women were allowed to study art there also needs to be critically reassessed, for they were still structurally disadvantaged. Most of them were sent to the textiles workshop because weaving was considered “feminine”, and they were not free to work in the field of their choice.

It’s important to address issues like gender equality, diversity and power structures in museum work, too. We have enshrined our commitment to human rights and anti-discrimination in a code of conduct. Our institution takes a clear-cut stand against right-wing extremism in a series of events entitled “Haltung üben” (An Exercise in Defending Democracy).

We support research examining the Bauhaus from queer, feminist and postcolonial perspectives. Projects like Young Bauhaus or RaumLabor – which promotes artistic expression for preschoolers – bring young perspectives to the museum. Academic institutions and museums seldom welcome input from young people who have no training in the fine arts, which makes it all the more important to create a space like Young Bauhaus in which we can set our own priorities.

You’ve worked on several exhibitions and projects since the creation of the Young Bauhaus, including young bauhaus. inbetween identities (2024) and Unfolding Futures. The Art of Growing Up (2025). How do you connect personal experiences with social issues in your works? What have been your personal highlights?

Jorna: Past exhibitions have allowed plenty of scope for personal experiences and social issues, which has given rise to highly individual works. In Unfolding Futures. The Art of Growing Up, I processed my own feelings about growing up and tied them into questions that lots of people ask themselves: Who am I? Where do I belong? The exhibition made me realize how many people can relate to that. One special highlight for me was the Friendship Book, an educational project in which exhibitiongoers could share their thoughts on the subject of our exhibition. Leafing through it, you find feedback from people from all over the world.

Sophia: For the exhibition, I built an architectural model of a house that opens like a flower, symbolizing change, personal growth and the transition to adulthood. The title is Entwurzeln. Entfalten. Wachsen (Uprooting. Unfolding. Growing). I was interested in how architecture can be more than just a functional space. The model ties my interest in design into the desire not to lose our imagination and creativity as we get older. The playfulness many people associate with childhood is often an important part of self-discovery – and soon suppressed in everyday adult life. So it was particularly heartening to see how many very personal works came together in the exhibition. Each of them was different, and each showed in its own way that growing up is not a clear-cut path: It means something different to everyone.

Sonja: My personal highlights are always the buildup days and the opening afterwards. Everything we’ve been working on for months comes together – and suddenly there’s a mounted exhibition! At the opening, it’s just great to celebrate together and to finally be able to show all our work to friends and family.

Lisa: I’m always surprised how different all the participants at Young Bauhaus are and how we manage nonetheless to reach decisions together that make everyone feel represented in the exhibition. Friendships and even love have blossomed at Young Bauhaus, which is a wonderful thing to see and experience.

What are you currently working on? Is there a project that’s really means a lot to you – or one you dream of realizing? What would that be?

Young Bauhaus is currently on summer break, an important phase in which we reflect on the previous year, write up reports and document what we’ve learnt from the collective exhibition process. We’re already preparing for the new year, which starts on September 1 – with fresh faces, new ideas and a focus on different priorities.

For our next step, we’d like to give Young Bauhaus greater visibility online – with an Instagram account of our own, for example, on which to post our own content. It’s not about coming up with perfect content, but bringing out the special character of Young Bauhaus. Many young people could relate to this authentic presence even in digital form.

We can also imagine experimenting even more with forms of artistic expression, such as a Young Bauhaus performance or a film about social cohesion in Berlin. Another dream of ours is to draft a collective manifesto in which the group articulate their vision of the museum of the future.

What all these ideas have in common is that the impetus comes from the group. We coordinate, network and support them, but the focus is always on what really moves the participants, what they want to create, design or change. Young Bauhaus is not a set format, but an evolving project. And that’s precisely what makes it so exciting.

What are your goals for the near future? What direction do you want the development of Young Bauhaus to go? Do you have a vision for the project?

Our visions for Young Bauhaus are diverse and open-ended: We want the project to keep growing and to get even more young people interested in and enthusiastic about the Bauhaus and museum work. Each group come with their own issues, ideas and approaches, so we, as the organizing team, are constantly learning something new. This keeps the project alive and continuously evolving.

When the new museum building finally opens in 2027, we look forward to throwing a big party in the glass tower to celebrate with everyone who’s ever been involved in the Young Bauhaus project!

Do you have any words of advice for creative young people (in Korea)?

Jorna: Believe in yourself and your ideas. Look for a community in which you feel comfortable trying new things. Art thrives on sharing, developing and experimenting with ideas. Working together at Young Bauhaus has not only enriched our collective efforts, but also encouraged each of us to develop artistically and explore new paths on our own.

Sophia: If you can relate to what Young Bauhaus is all about – and there’s nothing like it yet where you are – then just get started. We started small once too. We’re the third-year group now, but Young Bauhaus would never have grown so much without the groups that came before us. It doesn’t take much: just a place where people can get together and enjoy art and sharing ideas. Over time, that can blossom into something really beautiful.

Sonja: Stick together, try things out and have the courage to ask for whatever you need to be creative!

Lisa: The world needs your creative ideas and perspectives. Look for people you can share ideas with, people who listen to you and who challenge, inspire and support you. And don’t forget: It’s always okay to fail

Interview partners

Links on the topic: