"Yes to Dance No to Drugs"

By Dominic Zinampan, 2020In 2019, politician Bong Revilla, freshly acquitted of plunder, danced his way back into the Philippine Senate. His campaign video did not show his election platform nor his past achievements. Although he is a professional actor, he chose not to shoot scenes of himself pretending to be one with the toiling masses, or to make statements of how community service is his deepest passion. He simply danced to budots.

Bong Revilla’s campaign ad, »Sen. Bong Revilla - #16 sa Balota,« uploaded to YouTube on April 28, 2019.

I first heard of budots sometime around early 2016. Two memories immediately stand out, although I cannot recall which came first. A few friends of mine started sharing the half-decade-old Budots Budots Dance YouTube videos on social media just around the same time the »Hala Mahulog« meme became immensely popular. The meme shows a man standing poolside, who starts teetering after he is bumped by a friend. His desperate attempt to remain steady soon transitions into a spasmodic and wriggling dance. The meme’s name is taken from what someone supposedly yelled offscreen — a knee-jerk response indicating worry that the person might fall — which was then manipulated into a propulsive beat augmented with a wobbly bassline and a laser-like synth.

»Hala mahulog log log log (Budots)« uploaded by Edmon Nagora on March 12, 2016.

»Budots Budots Dance 1« uploaded by Sherwin Tuna on February 3, 2009.

Learning about budots felt almost epiphanic as it finally gave a name — which I had been searching for for years — to the loud, repetitive, and playful music I would hear at barangay (village) parties or while commuting to my 10am class; music that reminds me of the garishly designed bootleg remix CDs sold by the hundreds at wet and dry markets, and of the kitschy tracks our high school Phys. Ed teacher would make us do warm-ups to. This genre stood out for me as it seemed to be incredibly flexible – capable of absorbing and hijacking canonical OPM (1) tracks, 1980s US-American power ballads, mid 2000s pogi rock (2) classics, or whatever songs are popular at the moment – and turn them into gritty, mind-numbing bangers.

Some consider budots to be The Philippines’ first truly original electronic music genre. In an interview with VICE, Jay Rosas, co-director of the 2019 documentary, Budots: The Craze, described it instead as a »Pinoy-fied (Filipino-fied) electronic music genre.« Budots has also been connected to »bistik,« a portmanteau combining the words »Bisaya« (3) and how Bisayas articulate the word »techno.« (4) Although budots undeniably sounded familiar to me, I nonetheless found it difficult to specifically cite similar genres. Many budots tracks on YouTube mention EDM, techno, trance, and house in their titles and descriptions, but these hardly describe the genre’s sound.

According to blogger Ian Onyot in a 2012 post, budots is »a crossbreed of European techno music and bad hip hop.« (5) Although it is uncertain what he meant by »bad hip hop,« one may nonetheless discern similarities between budots and the more ribald and bacchanalian strains of the genre, such as Miami bass and crunk. Onyot was closer to the right track with European techno as budots does sound like a counterfeit of eurodance, clandestinely jerry-rigged. With 140bpm four-on-the-floor patterns, budots reanimates the corpse of eurodance, albeit stripped of the latter’s melodramatic singing and theatrical piano melodies, and discarding the expressions of emotional vulnerability in favor of obscene jokes and calls for riotous partying. Pulsating, thumping basslines accent the upbeat while chintzy synths, oft-described onomatopoeically as »tiw-tiw,« reminiscent of rayguns, sirens, and noisemakers, snake through high and low. Vocals may come in the form of spoken phrases but more often than not appear as chopped and looped samples. Tracks generally do not contain verses, choruses, and all the other trappings of pop songcraft; instead, energetic beats are stitched together and ornamented with cheesy sound effects like vinyl scratches and chipmunk laughter. Transitions and fills are also common, and it is during these brief moments that artists like DJ Love, DJ Arjay, DJ Ken, and DJ Arnold promote themselves along with their various affiliations such as mix clubs and mobile sound systems.

With 140bpm four-on-the-floor patterns, budots reanimates the corpse of eurodance, albeit stripped of the latter’s melodramatic singing and theatrical piano melodies, and discarding the expressions of emotional vulnerability in favor of obscene jokes and calls for riotous partying.

When I first saw Tuna’s videos, budots felt unlike all the other flash-in-the-pan dance crazes and viral challenges that had previously blown up. It did not come with a specific set of moves like »Otso-Otso,« »Papaya,« or »Spageti,« nor did it stem from some international pop sensation like »Asereje« or »Gangnam Style,« but most importantly, it did not come from the mainstream. It wasn’t devised by some studio’s in-house composers and choreographers, nor did it debut on a noontime variety show. Although there currently aren’t any definitive texts on the history of budots, in most narratives, budots was primarily grassroots, emerging from working class barangays in the Mindanao region in Southern Philippines.

By the time I, along with most Manileños, became aware of budots, it had already been popular for years. It was first featured on the popular television news magazine show, Kapuso Mo, Jessica Soho in 2012 and it reappeared in a 2019 episode of the same show, in which the presenter mentions how it never went out of style. Budots was also the subject of an undergraduate thesis written and submitted by Fritz Flores in 2010. In his research, Flores notes that budots music was regularly played in 2007 by several radio stations based in Davao City on the island of Mindanao. Additionally, its dance was already featured on local and national television programs largely due to comedian Ruben Gonzaga (9). Friends of mine who grew up in Davao City recall how, around this time, budots remixes of Top 40 hits were played everywhere, from taxis to malls, family reunions to fiestas, before its popularity somewhat dipped around 2011. They recall how bewildered they were by its sudden reemergence on a national scale a few years later.

Regarding the birthplace of budots, the consensus is that it originated in Davao City. It is also widely believed that it is Cebuano-Davao slang for »slacker.« (10) However, in his research, Flores presents the lesser known theory that the etymology of budots is »burot« meaning »to inflate,« a euphemism for glue sniffing. Flores also suggests that the bizarre dance started as a way for juvenile delinquents to disguise their drug use, particularly the inhalation of contact cement which is commonly referred to as »rugby,« hence the dance’s early association with drugs and street gangs. Flores also noted that some believe that the dance originated from, or was at least popularized by, residents of the Davao City barangays of Matina Aplaya and Leon Garcia.

Following the release of Budots: The Craze, many assume that Sherwin Tuna (DJ Love) single-handedly created both the music genre and the dance. His YouTube channel has around 80,200 subscribers and over 37,680,000 views and he is perhaps the genre’s most prominent figure. His videos show his groups, CamusBoyz and CamusGirls — named after J. Camus street in the Brgy. 9-A (Barangay 9-A) neighborhood, also in Davao City — dancing to tracks that he mostly produced himself using FL Studio in a run-down internet café he manages. Tuna is conscious of budots’s disreputable image, from which he constantly distances himself and his dancers, perhaps most visibly through the slogan »Yes to Dance / No to Drugs,« found in most of his videos. Such a statement can also be read as support for the Duterte administration’s deadly War on Drugs.

When I was invited to write this essay, one of the research angles suggested was to discuss any political potential or meaning in budots. Being a middle-class Tagalog-speaking Manileño — there are many barriers to my engagement with this phenomenon. For one, I do not understand most of the titles, lyrics, and soundbites on a lot of budots tracks as most of them are in Cebuano, a Visayan language colloquially referred to as »Bisaya« and spoken mainly in Central Visayas and most of Mindanao. (11) Budots’ history is one deeply rooted in Bisaya culture and working-class communities, and my failure to acknowledge the differences between this context and my own subject-position would repeat the widespread tendency of many Tagalog-speaking Manileños to generalize their experiences as definitive of »Filipino culture,« glossing over its actual heterogeneity that encompasses around 130 languages and even more ethnic groups.

Budots’ history is one deeply rooted in Bisaya culture and working-class communities

Even worse, Manila-centrism extends beyond mere ignorance. Muslims, Indigenous peoples, and even those from other Tagalog-speaking regions have become objects of Manileño snobbery, with jokes painting them as unsophisticated and backward. This cultural hegemony has gradually bred disdain for Manila, something that Rodrigo Duterte capitalized on in his 2016 presidential campaign (one of his main political platforms was a shift towards federalism.) Even Duterte’s profanity-laced speeches and other »unstatesmanlike« antics have earned him some supporters, who embrace the stance as »Bisaya culture,« in contrast to the stuffy decorum of the established elite and his Imperial Manila-perpetuating predecessors and opponents.

There are other occasions, aside from Bong Revilla’s senatorial campaign, where budots has touched political discussions. During the opening of the 2019 SEA Games, First Daughter Sara Duterte-Carpio expressed frustration over the decision to use Hotdog’s 1976 song »Manila« for Team Philippines’ entrance, suggesting budots could have been used instead since fellow Davaoeños »invented« it. (12) Although her disapproval is understandable, her comment appears to be aligned with her father’s federalist agenda, something which many suspect would give more power to the established regional political dynasties. Rodrigo Duterte himself, in his seventh term as Davao City Mayor and months before he officially announced his presidential bid in 2015, danced alongside the CamusBoyz in one of DJ Love’s videos.

»Budots Budots Dance 12” with Mayor Duterte« uploaded by Sherwin Tuna (DJ Love) on June 16, 2015.

It seems that rather than threatening the status quo, budots presents an opportunity for politicians to characterize themselves as more down-to-earth or anti-establishment than other equally established political figures, and thus secure the support of certain demographics. So far, the closest I could find to budots being used along the lines of protest is BuwanBuwan Collective’s Soundcloud playlist Bakunawa Vol. 7: Rodrigo Duterte’s Summer Budots Party. The product of an open call that required, among other parameters, that all submissions contain vocal samples of Duterte, the compilation seems more like a joke without a critique. It is also hard to tell whether or not it parodies the genre in addition to the president. As a friend who grew up in Davao City suggested, the bourgeois and Manileño reception of budots seems to be one of irony at best, and of ridicule at worst.

It seems that rather than threatening the status quo, budots presents an opportunity for politicians to characterize themselves as more down-to-earth or anti-establishment than other equally established political figures, and thus secure the support of certain demographics.

There is an illusion that budots transcends social classes, that it has the potential to unite multiple sectors. However, categories of »high« and »low« culture remain, or are maybe even reinforced within its framework.

(1) OPM, or Original Pinoy Music, is a vague label encompassing a wide range of Filipino pop music. Among the genres considered distinctly OPM are »Manila Sound« or disco pop from the 1970s, folk rock, easy listening, and other adult contemporary genres, alternative rock from the 1990s and 2000s, acoustic pop, hip hop, and many others.

(2) Pogi rock, from the word »pogi« meaning »handsome,« is a derisive label used to describe alternative rock or post-grunge bands that were active in the mid-to-late-2000s and were dismissed by some for being famous solely on account of physical appearance. A vitriolic rant written around the peak of pogi rock can be read here: https://twoisequaltozero.wordpress.com/2007/03/24/why-pogi-rock-is-even-more-awful-than-boybands/comment-page-1/.

(3) Bisaya is the name of a large ethnolinguistic group in the Visayas islands and Mindanao region and the colloquial term for the Cebuano language.

(4) Michael L. Tan, "'Budots' and Filipino." Inquirer, August 23, 2019. Accessed May 25, 2020, https://opinion.inquirer.net/123486/budots-and-filipino.

(5) Onyot, Ian. “Before ‘Dougie’ and ‘Gangnam Style,’ There is ‘Budots.’” MagWrite (blog). September 13, 2012. Accessed May 22, 2020. http://magwrite.blogspot.com/2012/09/befor-dougie-and-gangnam-stylethere-is.html-

(6) Lex Celera. “The Origins of Budots, the Philippines' Catchiest Viral Dance Craze.” VICE, September 10, 2019. Accessed May 22, 2020. https://www.vice.com/en_asia/article/xwewa3/the-origins-of-budots-the-philippines-catchiest-viral-dance-craze.

(7) The Sama Dilaut, more commonly known as the Badjaos, is an Indigenous group who arrived from Borneo six centuries ago and settled along the coasts of Sulu, Tawi-Tawi, and Zamboanga in Southern Philippines. They are often described as »sea vagrants« and are renowned for their skills in diving and fishing. A large population has since been displaced and the Badjaos are now known for being mostly nomadic, with many performing in jeepneys and public areas for money (see Lagsa, Bobby. “Plight of the Badjao: Forgotten, nameless, faceless.” Rappler, December 5, 2015. Accessed July 2, 2020. https://www.rappler.com/nation/114975-badjao-nameless-forgotten-faceless, and Soriano, Zelda. "The Badjaos: Cast Away From Mindanao To Manila." Bulatlat. Accessed July 4, 2020. https://www.bulatlat.com/archive1/006badjaos.htm.) Although many have pointed out the similarities between the dance and music of budots with the Badjao’s forms, I couldn’t find any reliable sources elaborating on these. It is my guess that when others draw a comparison, these are the dance and performance styles that they have in mind. It is hard to tell whether or not these forms — that are often associated with the Badjaos — influenced budots or were themselves influenced by budots.

(8) Jessica Soho. "Kapuso Mo, Jessica Soho: The Alimango Dance craze is in!" YouTube. Video File. August 26, 2019. Accessed June 3, 2020.https://youtu.be/-AWbiVgg4x8.

(9) Flores, Fritz E. “Towards the Mainstream: A Case Study on the Budots Dance Craze.” Undergraduate thesis, University of the Philippines Mindanao, 2010.

(10) Celera, “The Origin of Budots.”

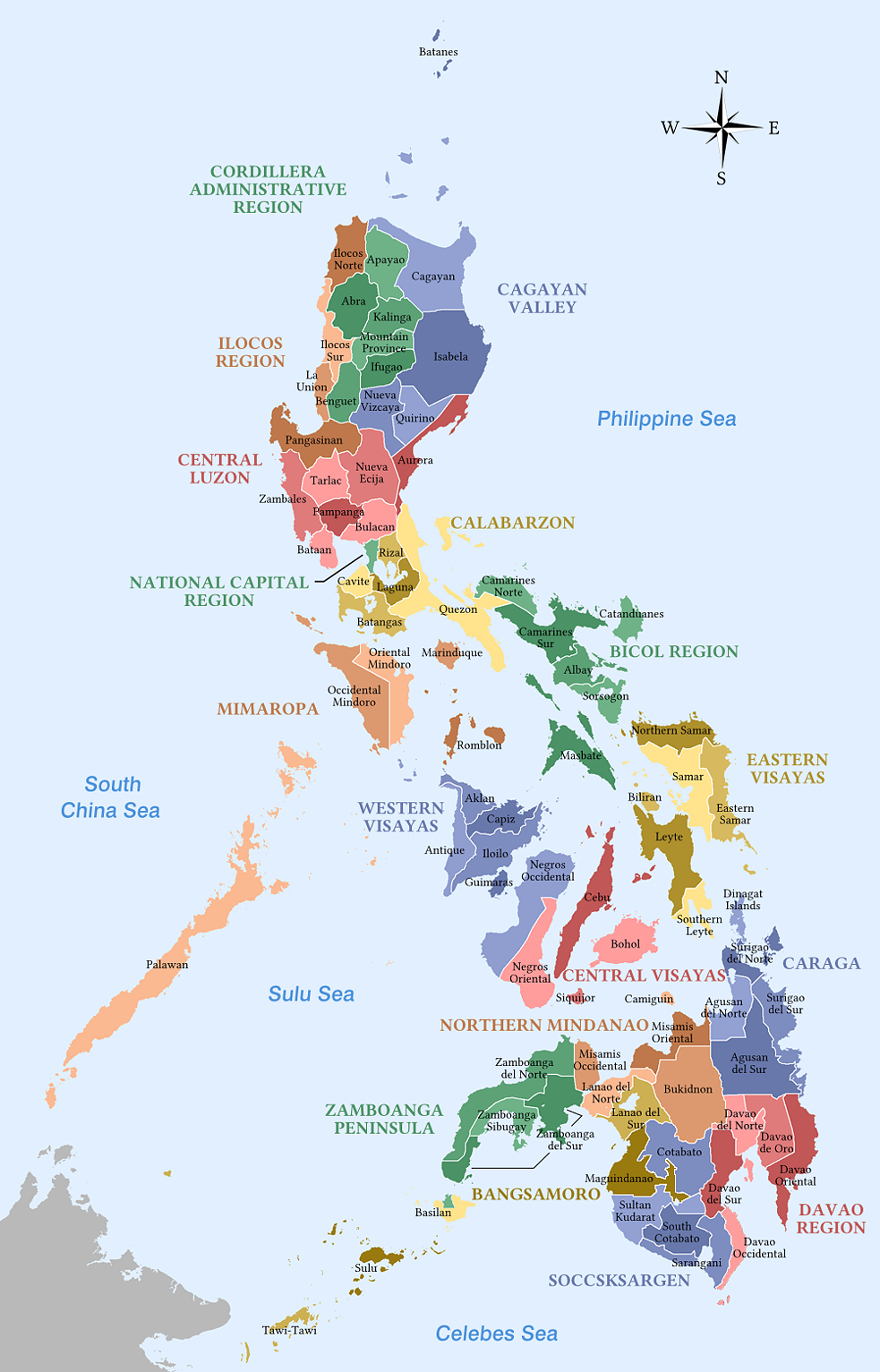

(11) The Philippines is divided into three main island groups: Luzon, Visayas, and Mindanao. Manila, the nation’s capital, is in Central Luzon, while Davao City (where budots is believed to originate) is found on the southern end of Mindanao. Cebuano is spoken in most of Mindanao (including Northern Mindanao, the Zamboanga Peninsula, and the Davao Region), as well as Central Visayas in the islands of Cebu, Bohol, and some parts of Negros and Leyte. Tagalog is spoken mainly in Luzon, the largest of the three main island groups of the Philippines. Aside from the National Capital Region, also known as Metro Manila, Tagalog is also widely spoken in Central Luzon (some parts of Region III) and Southern Luzon (most of CALABARZON and MIMAROPA).

(12) Hernel Tocmo. “Why ‘Manila’? Sara Duterte questions entrance theme at SEA Games opening.” ABS-CBN News, December 1, 2019. Accessed June 10, 2020. https://news.abs-cbn.com/news/12/01/19/why-manila-sara-duterte-questions-entrance-theme-at-sea-games-opening.

(13) The meaning of mañanita in Filipino culture comes from Mexico, where the word describes the celebration of someone’s birthday by singing a special song to wake up the birthday person after midnight or at dawn. In contrast to a birthday party, a mañanita is a very simple celebration, usually attended by immediate family members only. In the words of Interior and Local Government Secretary Eduardo Año, “Hindi talaga siya party.” (“It really isn’t a party.”)