Wars and climate catastrophes are creating food shortages around the world. Nonetheless, an equitable global food supply is possible – though only if we change our production methods and consumer behaviour.

Every day at shortly after six o’clock Thomas Omoni gets up and wakes his youngest son Regan, who has to go to school. Recently, their meals together have been less harmonious. “Regan often complains about the food now,” laments Omoni, who earns a living as a driver. “We used to have mandazi for breakfast,” he recounts. Mandazi are fried dough balls that require not only cooking oil but also wheat. Since the outbreak of war in Ukraine, both have become considerably more expensive in Kenya. Because they need to save money, Omoni and his wife now eat plantain in the mornings, but Regan protests against the unfamiliar food. “So we often buy a mandazi for him nonetheless,” admits Omoni. And while the adults drink their morning tea – now without sugar, which was virtually inconceivable in Kenya before the war – Regan still gets his slightly sweetened because he would otherwise make too much of a fuss.The cost of living has risen dramatically in Kenya over the past few months. Besides cooking oil, the prices of milk, household gas and cornflour – the most important basic foodstuff in Kenya – have also increased considerably. This is partly due to the fact that the government has significantly hiked the taxes on many products because the country is experiencing a debt crisis and the government is desperately seeking further sources of revenue. It has doubled the VAT on propane gas from eight to 16 percent, for example.

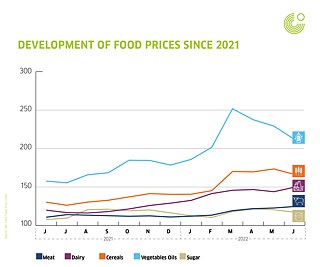

Ukraine War Exacerbating Shortages

Since February, the consequences of the Russian invasion of Ukraine have been compounding the problems. Before the war, Ukraine and Russia combined produced two thirds of the cooking oil exported worldwide, and a third of global wheat exports. 15 percent of corn, which is likewise a key basic foodstuff in many countries, also came from Ukraine and Russia. According to recent UN estimates, sub-Saharan countries imported around 44 percent of their wheat from Russia and Ukraine – and the figure in Somalia even exceeded 90 percent.

رسم بياني لواردات القمح من روسيا وأوكرانيا | Graphic: © FAZIT Communication GmbH

Hopes That Agreement Will Ease Situation

An agreement signed on 22 July 2022 could ease the situation somewhat. In a deal brokered by UN Secretary-General António Guterres, Ukraine and Russia agreed with Turkey on a solution that would allow millions of tons of grain to be exported from Ukraine. The agreement provides on the one hand for a corridor that cargo ships could pass through safely. And on the other hand it stipulates that vessels must undergo checks to ensure that no weapons are transported. A ship with wheat on board was able to leave Odessa on the first of August 2022. However, it remains to be seen whether the warring parties will respect this agreement.Exports of foodstuffs from Russia could already continue in the past weeks because they are exempt from the sanctions. “Russia is the world’s biggest wheat exporter,” notes Matin Qaim, a professor of agricultural economics, an agricultural scientist, and one of the directors of the Center for Development Research (ZEF) in Bonn. “And it also boasts roughly ten percent of the world’s arable land.” President Putin is using this production potential very strategically at present, he explains. “In other words, Russia is exporting only to friendly countries, or to countries that are amenable or are to be made amenable.” According to Qaim, Russia is now – after a brief suspension of exports in March – exporting over 80 percent of its pre-war volume again, but quite intentionally only to certain countries. “And there is of course a very real risk that dependence on such imports from Russia will divide the world up in new ways – with Russia-friendly states that are dependent on these imports from Russia and others who are not.”

Rising Energy Prices Make Products More Expensive

At the same time, energy prices have exploded due to fears of shortages. This makes all transport options more expensive, which almost inevitably drives up prices. Countries like Kenya face an additional dramatic problem, namely that important nitrogen fertilizers can only be produced using methane from natural gas. As a result, these artificial fertilizers have also risen in price because of the war.

Climate Crisis Exacerbates Food Insecurity

The Indian export ban is another example of the dramatic impact that the climate crisis will have on food security in the coming years. The life-threatening consequences of the climate crisis for people on low incomes are also visible in the Horn of Africa. And currently it is not only the east of Africa that is experiencing a severe drought – West Africa is too. Nearly 40 million people there could soon be hit by famine.Low Productivity in African Agriculture

The increased occurrence of extreme weather events is not the only reason for the massive shortage of foodstuffs. Christian Borgemeister, likewise one of the directors of the ZEF at the University of Bonn, highlights rapid population growth. “The increase in production has not kept pace with this,” regrets Borgemeister.And yet there is a whole host of countries that could produce considerably more, adds Qaim. “For decades, agriculture and agricultural funding have been criminally neglected.” This is because the model of development that has been promoted internationally since the 1950s has seen industrialized nations and countries of the Global South pin their hopes primarily on industrialization. “Agriculture was not encouraged; instead, people looked for ways to drive forward industry,” explains Qaim. This was a mistake, as has now become clear. In contrast to Africa, however, many Asian countries have been investing more in agriculture since the late 1960s and 1970s within the framework of the Green Revolution “because the important role that agriculture plays in combating hunger and poverty was gradually recognized,” says Qaim. “The Green Revolution did not take place in most African countries, however.”

Paths Towards an Equitable Global Food Supply

Qaim and other experts are convinced that an equitable global food supply is possible even against the backdrop of wars and climate disasters. “This would require greater sustainability in consumption,” emphasizes agricultural economist Qaim. And above all this would mean less waste, and less grain being used as feed for animals. “We thus need to move away from the high levels of meat consumption that we have seen, especially in rich countries.” At the same time, in places where conditions are conducive to agriculture, production would need to be promoted in a sustainable and environmentally friendly way.The Kenyan agricultural economist Timothy Njagi also calls for more support for agriculture in African countries. Though the EU has been funding agricultural projects in Africa for some time, he says that it mainly does so in pursuit of its own interests. For example, Europe wanted to see dairy farming intensified. “In most regions of Africa, however, the dry conditions mean that extensive grazing is the only option for cattle farmers,” stresses Njagi. The EU’s programmes there came to nothing. The Kenyan scientist believes that one key factor in ensuring a globally equitable food supply is greater transfer of knowledge. This also applies to the EU’s “Green Deal”, which aims to make Europe climate-neutral by 2050. The EU hopes that this will set global food standards.

African countries will also have to produce more organic food in future if they want to export to Europe. “But we are not effective enough as yet,” says Njagi. Rather than placing new trade obstacles in Africa’s way, Europe should for example use information technology to share its knowledge about organic pest control options. Njagi proposes greater cooperation between African and German universities. “On the basis of what Germany has already developed, our scientists could find local solutions that are tailored to the conditions here and work just as well,” he is convinced. “Rather than us simply copying and transferring practices that are applied elsewhere.”

August 2022