Cologne, New York City, and New Orleans

How to Walk in the City

This episode is a reflection on what it means to walk in a city — how walking can be anything from a mode of transport to a meditative practice.

Listen to this episode: Apple Music | Spotify | Download

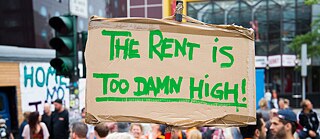

This episode comes from Thomas Reintjes. As an independent radio producer and journalist, Thomas mainly works with Germany’s national public radio station Deutschlandradio. Since 2013, he has been based in New York City. In this podcast, Thomas talks to writers Lauren Elkin and Garnette Cadogan. Thomas took the featured photo while walking in Berlin.

Transcript

[DISTANT STREET NOISE]

Garnette Cadogan: So there’s something about walking through a neighborhood in which there’re apartments or houses flanking on both sides and thinking that, you know, on both sides of me are people going about their lives, laughing, eating, arguing, cooking, loving, disliking, living. Just even walking in an empty street, but knowing that you’re walking past lives being lived.

[MUSIC]

Thomas Reintjes: My life in New York began with hauling my suitcase out of the subway on Astor Place and looking up. High rise buildings stared back. One of them my new home. My boyfriend had started a new job here and found a studio apartment for us. I remember making my way through the traffic of the West Village, dragging my suitcase behind, looking down at the big slabs of concrete, the sidewalk under my feet.

What makes you turn left here?

Garnette Cadogan: Because I looked up straight ahead and it just seemed empty and I thought maybe, you know, left here, there were something more interesting on the streets. Maybe people hanging out outside and so you might see stories spilling out onto the streets. When I came to New York, a few months after being here, I began dating someone and we dated for four years and so much of my movements around the city was a movement with her. A movement towards her. Meeting her somewhere, going somewhere with her. And so after we broke up, so much of my walk in the city was about trying to get over the pain of that breakup. And part of that meant, places which were shaped, stories which were told, maps which were created by my walking with her, suddenly had to be shifted and I had to try to start looking for new routes, because those old routes brought back stories that were painful to remember.

[STREET NOISE, TRUCK PASSES BY]

Thomas Reintjes: I’ve been finding new routes through the city, too, avoiding the West Village. I live in Brooklyn now, with a new boyfriend. The slabs of concrete sidewalk remain the same. Some people have left imprints in them when the concrete was still fresh and moldable.

Lauren Elkin: I didn’t grow up walking for fun, necessarily. It was always just the way to get from, you know, point A to point B, so I grew up out on Long Island in the suburbs — you’d drive from one place to another and then walk from your car to wherever you’re going. And you’d try to park as close as possible to wherever you were going, like you go to the, whenever I go home now and I drive to the mall — that’s where you have to go to do any shopping — you see the people like fighting over these parking spaces that are close to the entryway and then the ones that are bit further away are all desolate. It’s like why, why is it so awful to walk like an extra two minutes, you know. Anyway...

Thomas Reintjes: Well, it’s walking across the parking lot which is not that exciting.

Lauren Elkin: It’s not like the worst thing in the world to walk a little bit. So, yeah, it was really when I went to University in New York City, that I discovered like, I can actually just use my legs. And there’s so much to see in between. And that was the beginning of this whole sort of way of thinking about the world, which is based around, you know, actually physically being in it instead of just passing through it quick speed.

[MUSIC]

Thomas Reintjes: Back in Cologne, if I wanted to go for a walk, I’d head out of the city. To a forest, along a riverbank, or to a park at least. Some of my favorite childhood memories are from hiking vacations in the Alps, climbing mountain tops and picking blueberries on the way back down. Now, in New York, it’s hard to get away from everything just for a stroll. When I walk the streets, I pick the quieter blocks, always trying to get away from traffic and crowds.

[STREET NOISE]

Garnette Cadogan: As a kid when I began walking alone, I wanted to be away from home as much as possible, because I had a stepfather who was quite cruel. And the more time I spent in his presence, was the more time I have been beaten for no reason at all and being abused. I’d go to some street party or go to a movie, and leave and then walking around late and too late to get public transportation back home. And when I was walking back home, I’d see other people who were leaving work or leaving the home of a friend. And so I would begin talking to these strangers on the streets and they’d begin talking to me and I was in school uniform because in Jamaica every school had a uniform, and this would be ten o’clock or 11 o’clock at night, and they were wondering why someone in their school uniform at age 10 or age 11 walking at this time of the night and walking in the direction of what are clearly dangerous neighborhoods. There’s a certain fearlessness. Which itself came from a certain folly from then in which I walked, you know through neighborhoods that I don’t think I’d walk through them now as an adult. And so I just felt very carefree, I felt that nothing would happen to me.

[MUSIC]

Thomas Reintjes: When I’m walking, I like to pretend that I’m invisible. That it doesn’t matter who I am. I’m just passing by. Minding my own business. Not interfering with the world. I’m not a tourist. I live here. I’m not a gentrifier. I’m not even here anymore. I have already moved on.

[STREET NOISE]

Garnette Cadogan: I went to school in New Orleans and I was in college there. And as it turns out, I started discovering in mere weeks after I got there, that there’s a difference in how I could walk as a black person in that city versus my peers, my classmates, who were white who were also walking through that city. One afternoon, late afternoon, I was coming from an event, a school event, and crossing a crosswalk and someone in a wheelchair had his wheelchair got stuck in a pothole. And I offered to push him out of it and push him to the other side of the street and he just snapped at me, threatened me, threatened to shoot me in the face with a gun and then right after ask a white student who was also crossing the street to help him across. And I couldn’t help but ask, you know, was it race? Maybe it was something in the way I approached him, maybe something in my Jamaican accent threw him off, who knows? But it stuck in my head that this seems to have been about race. And then, after that one event after another began happening. People would see me at night and they would call the cops. The cops would tell me that somebody reported someone suspicious walking up past them or towards them, people would clutch their bags and cross the streets, people would be walking ahead of me at night and turn and see me and sprint ahead. And so event after event kept popping up, which made it clear that walking as a black person was a different experience in New Orleans than walking as a white person.

Lauren Elkin: Where is it? This sort of area over there with the pylons. I’ve walked through that when there have been guys kind of idling around, sitting and I don’t know what they’re doing. And yeah, I think it’s, when there are people there, if I were by myself or you were by yourself, it would be a different experience for me or for you, which is not to say that like men don’t feel threatened in public space, either. This, you know, they do. And for lots of different reasons, having to do with class and race and presentation. I’d like to think that if I were walking with like confidence, a kind of fuck-you-look on my face, like no one’s going to mess with me. But I’m sure that’s not true. It’s not really up to me how people in public space react to me. It’s more up to them to leave me alone or not. It’s something that I’ve been thinking about since He Who Shall Not Be Named was elected in America and the day after the inauguration we had this massive Women’s March in DC and around the world. And it was amazing to see on the news that night, how many women had turned out, you know wearing pussy hats or whatever, but how many women had turned out to show themselves to say like I'm putting my body in this physical environment so that you can see what I stand for. I’m here and I’m declaring it and you have to deal with me.

[MUSIC]

Thomas Reintjes: In Berlin, sidewalks are made of tiny cobblestones, randomly shaped and uneven. Roots lift them up from beneath, making themselves known. I can feel them through my sneakers. When I walk on flat slabs of concrete, I can’t feel anything ... and I wonder what’s been erased underneath.

Garnette Cadogan: I do things to mark me as safe. So if it meant wearing a shirt that had the university Insignia on it, I would do that sometimes to say: oh, he goes to university here. He’s a university student. He’s safe. Or I would dress sometimes in brighter colors, so I’d wear pants that was, let’s say a khaki pants. I dressed like a nerd or I would look preppy. And that did mark my safe. And so therefore I could then have more freedom navigating through places and having less harassment. I continually forget things at home and have to run back because I’ve forgotten this one item or this next thing. And so I’d be going somewhere and go. Oh I’ve forgotten that, let me run back. And I turn and run back and recognize, how running would cause these problems. Because it had happened more than once, where I forgot something and I made a sudden turn and a person behind me would either scream or would freeze up and look scared. And so what I would do is that I would just walk straight to the end of the block, gently cross the street, and then move back in the other direction, moving in a slow, you know, relaxed pace, not looking hurried. Just so that they could feel relaxed or more assured that things are okay. There is something almost defiant in me that says, this is a basic right. This is a commonplace practice. I shouldn’t have to give it up because of your suspicions. So the way the police would treat me at times or the way people who are suspicious of me because my race would treat me at times would never let me stop walking, far from it. This is too basic a practice. Too essential a practice. Too essential to being human. It’s one of our first acts of independence and freedom. Think about it. It doesn’t matter how many times you’ve seen it: the act of a child taking its first steps never gets old. So there’s something about walking, that is so symbolically powerful, a baby taking its first steps symbolizing a level of freedom, a level of independence, a level of discovery. The first full true act of freedom. It’s that promise of independence, the way no other human act does. Walking has not only become a way to move through life, but this has become a way of life a way of thinking and seeing and interacting with the world.

[MUSIC]

Thomas Reintjes: You can’t walk in my shoes and I can’t walk in yours. But we walk the same streets, our feet pressing into the concrete, trying not to trip on the cracks. Many thanks to my walking teachers, the writers Lauren Elkin and Garnette Cadogan. My name is Thomas Reintjes.