Musical Taste Show Me What You Hear

Mainstream music gets a lot of playing time on the radio. But mainstream isn’t the same everywhere: Why are Finns into heavy metal and Japanese listeners into Mozart? Christine Bauer researches the ways in which algorithms influence our listening experience and the extent to which national musical preferences deviate from the global mainstream.

Christine Bauer, you use big data to research the musical tastes of people – or more precisely, streamers – around the world. What is the object of your research?

The principal object of our research is to improve music recommendation systems – the systems that suggest what to listen to next or automatically complete a playlist. Tastes vary, of course – otherwise you could just recommend the same music to everyone. But the variance isn’t only individual, it’s also country-specific. We conducted a study to find out how musical tastes differ between different cultures and countries.

You’ve analysed 800 million songs streamed by users in 47 different countries on the platform Last.fm. What does such an analysis involve?

We looked into the streaming behaviour of 53,000 users: what songs they listen to and how often. Each stream is a data point. Since each artist usually has several songs to choose from on the platform, the data can also be aggregated at the level of each artist. We calculate the number of so-called playcounts per song, so if you listen once to five different songs by the same artist, that comes to a total of five playcounts for the artist in question. Using this data, we can find out which artists are particularly popular in which parts of the world.

So what did you find out? How do musical preferences vary from one country to another?

People in every country listen to the top superstars, which comes as little surprise. But if you filter these superstars out, you can make out country-specific differences. My favourite example is Finland, which is clearly metal-head country. Many of the top artists in the Finnish mainstream are in the heavy metal genre, which is something one hardly finds anywhere else. Japan is interesting too because its musical taste differs markedly from the global mainstream. Artists who rarely get streamed elsewhere in the world are very big in Japan: Mozart, for instance. Japan is the only country in which our analysis shows classical music way out in front. Then again, musical preferences in Japan aren’t limited to a single genre and on the whole they’re quite diverse.

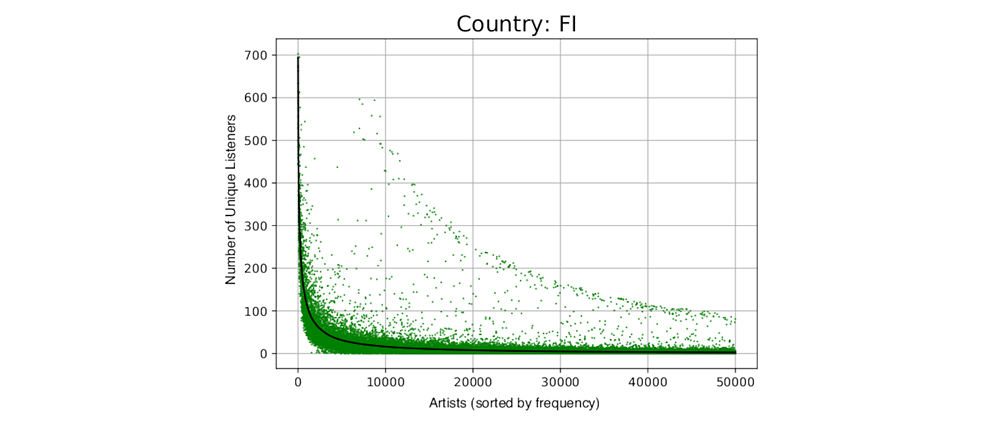

A case in point: global vs. Finnish mainstream. The black curve shows the global popularity (“global mainstream”) of musical artists in descending order. The green dots show listening behaviour in Finland, which clearly diverges from the global mainstream. Consequently, the curve formed by the cluster of green dots above the global mainstream curve represents the Finnish mainstream.

| Photo: © Christine Bauer

What about German taste in music?

A case in point: global vs. Finnish mainstream. The black curve shows the global popularity (“global mainstream”) of musical artists in descending order. The green dots show listening behaviour in Finland, which clearly diverges from the global mainstream. Consequently, the curve formed by the cluster of green dots above the global mainstream curve represents the Finnish mainstream.

| Photo: © Christine Bauer

What about German taste in music?

Like Finland, Germany has its own mainstream, which diverges from global taste in music. The international top superstars get streamed here too. But other artists who hardly have any international fans are very popular in Germany. Many of them are presumably German-language artists.

Which musical taste determines the global mainstream?

Needless to say, when I talk about the “global mainstream”, I don’t mean the dictionary definition. For our purposes, “global” refers to our aggregate data set – in other words, 47 countries. We looked at what people listen to in these countries overall and how often. The results coincide with the classic popularity curve in the music industry. Most of the music streamed is by a very small number of artists whom people listen to very, very often. This peak in the curve corresponds to the most popular music overall. Then the curve plummets and the section of the curve called the “long tail” begins. It covers a far greater number of artists, but their music is much less popular than that of the superstars. We call this curve of the entire data set the “global mainstream”. If you superimpose the global curve on that of a specific country, you can see the deviations. The deviations for Finland, for example, are more conspicuous than those of many other countries.

Do English-language artists dominate the global mainstream?

Our research wasn’t about what language the songs are in, but it goes without saying that most of the top superstars leading the global mainstream are English-language artists. Our study also shows that music preferences in the US and the UK in particular are closely aligned with what is globally popular. These two countries may help define the mainstream, but that sort of thing can’t be deduced from our data.

To what extent do the musical preferences of radio listeners coincide with those of streamers?

We didn’t look into that specific question. What gets aired on the radio is not necessarily what people want to hear and certainly differs from streaming behaviour. That’s probably due in part to various and sundry marketing campaigns. But songs we hear often enough on the radio will ultimately catch on on streaming platforms as well. Besides, some countries have mandatory quotas: French law, for example, requires that at least 35 per cent of the music played on the radio be by French artists.

Your research is also about the fairness of music recommendation systems. How can these systems be made fairer?

As I’ve said, our research seeks to improve recommendation systems in terms of user experience, the idea being to recommend what best suits their tastes. Naturally, this often deviates from the global mainstream. An algorithm based on users’ tastes is arguably fairer both for users themselves, who get more appropriate music suggestions, and for artists outside the mainstream, who reach more listeners as a result. We know, for example, that the current recommendation systems work best for mainstream listeners and worst for metal and hip hop fans. In my opinion, including a wider range of genres and sub-genres would be a good way to optimize recommendation systems.