Felix Heidenreich Life in the Kantian world

On the anniversary of Kant’s birth, Felix Heidenreich presents his novel “The Philosopher’s Servant”. Readers not only get to know the great philosopher Immanuel Kant from a different perspective, they also gain an insight into the lives of his inner circle. In this interview, Felix Heidenreich talks about Kant the “media junkie”, his morning routines and about the Enlightenment ideals that have enduring relevance in 2024.

Verena Hütter: Felix Heidenreich, your novel is enjoyable not just for people who are already familiar with Kant, but also for those who know little about the philosopher. How would you describe Kant in a few sentences to someone with little prior knowledge? What is the most important thing they should know?Felix Heidenreich: Kant is usually presented to us as the paradigmatic philosopher of the modern age. In this sense, we could say we live in a Kantian world, because we rely on reason, a universal concept of reason that can transcend all linguistic and cultural boundaries, a reason that will lead us to a peaceful, healthy and freer future. That’s one thing. The other is that Kant as a figure is emblematic of a certain notion of philosophy. He cultivated a very ordered lifestyle; he had a very coherent way of navigating life, leading his own life according to philosophical principles and pragmatic maxims. The life he lived was obviously meant to validate his philosophical work. This also makes him a hero as a person.

Incidentally, by European standards, Kant’s philosophy of the Enlightenment came relatively late – just as Germany generally came late to the great Enlightenment party (where the Scots and the French had been conversing for a long time). Perhaps this is why they were greeted with such excitement and applause, as is so often the case at parties. In this respect, Kant is both the pinnacle and the culmination of the Enlightenment, at least from a German perspective.

You decided to produce a novel rather than a work of non-fiction to mark Kant’s anniversary year. As a novelist, you discovered a beautiful setting – 18th-century Königsberg. Can you describe the city?

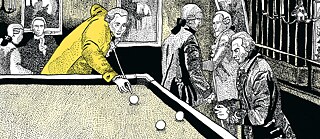

The astonishing thing is how intellectually lively public life in urban Königsberg was. Kant and his circle of friends, and the middle classes in general, were extremely curious about world affairs. They engaged in spirited debates and argued fiercely about complex philosophical matters. Königsberg was not a metropolis like London, but it was always indirectly involved in what was going on in the world: through Russian occupation and war, but also through English traders and a lively intellectual exchange with the world, via the press and correspondence. We can already see the emergence of a European public here, one that we can only aspire to today.

Kant never left Königsberg and yet he was interested in distant places. You once even went so far as to say that Kant, as a reader of travel reports, was “a kind of media junkie”.

That is indeed a rather exaggerated formulation, but it’s interesting that Kant made references to travel reports, especially in his lectures. For me, this points to the abysses and darker sides of the Enlightenment: the fact that the very person who calls on us in his essay What is Enlightenment? to use our understanding without guidance from others, is in many ways himself dependent on other people telling him all about the Persians and the French and so on. I think there’s a lot of unintended comedy but also tragedy in the fact that we see Kant struggling to live up to his own standards.

Kant is both distant and close to us.

It definitely helps. Lots of people who have left behind huge bodies of work led this kind of lifestyle. Johann Sebastian Bach, Honoré de Balzac or Thomas Mann are just a few names that spring to mind. You need effective management and a well-oiled machine to get your output right. I don’t mean that disrespectfully, but in admiration. I find it interesting that, on the one hand, Kant seems so distant to us, so compulsive and strangely rigorous. But on the other, he’s close to us.

We, too, live in an age in which people try to control their immediate environment. They follow diets, have fitness plans, morning routines, practise yoga and meditation: the immediate environment, which is controllable, is structured very rigidly. We could speculate that this makes up for the fact that our more distant environment is spiralling out of control. We’re experiencing war in Ukraine, turmoil and chaos in the Middle East and an impending climate disaster. All of this is largely beyond our control. So if we can’t control this, we can at least prepare bowls of muesli every morning according to a perfect plan.

Maybe Kant shared similar sentiments. He endured Russian occupation, was subject to an absolutist political authority and observed the chaos of the French Revolution. It was a time of profound upheaval. It’s conceivable that he, too, sought shelter within his own ordered environment. In which case, perhaps Kant is not as distant from us as he seems.

If we’re to believe your novel, Kant wasn’t always like this. He was something of a dandy and enjoyed spending time at social gatherings. However, then came the moment when he suddenly mutated from “elegant Magister” to ascetic. Is this grounded in historical fact or is this a product of your imagination?

It is undisputed that Kant had a kind of midlife crisis when he was around 40. We can only speculate about the reasons and its significance. I have included lots of historically authenticated details in my novel. The characters and numerous quotes come from historical sources. But, of course, I also took the liberty to embellish this story. I wanted to give an existential edge to his philosophical work.

I interpret Kant’s struggle to find reason and establish a firm foundation, to construct a “groundwork” for the metaphysics of morals and to attain philosophical clarity, as a response to an existential threat. Understanding the essence of reason also means escaping delusion and madness. The ghost and shadow motif is therefore key. Kant scholars around the world may correct me, but I maintain that Kant can be interpreted in this way: not as pure theory and a philosophical “glass bead game”, but as a response to a profound existential shock and uncertainty.

A merchant proofreads the philosopher.

I find Joseph Green to be an exceptionally interesting figure. Apparently, he really did discuss the Critique of Pure Reason with Kant, passage by passage. It’s remarkable that something like this was possible in the 18th century, that a merchant could proofread masterpieces of contemporary philosophy while carrying out his own professional duties! It’s emotive, too, because it means we should reflect on whether it is really desirable to live in a society of differentiation and specialisation, where everyone focuses solely on their own small area of expertise. Seen in this context, Joseph Green is a fascinating character.

But I was also drawn to the other people in Kant’s circle. I didn’t have to invent much more. The characters were bizarre enough in their own right; all I had to do was put together the material they provided.

Kant’s companions seem to have been largely overlooked in the past. If you search for their names on the internet, you don’t get many hits.

There’s some information about Theodor von Hippel, because he wrote a bizarre treatise on marriage, and there are also a few things about Ehregott Wasianski, Kant’s first biographer. But I wasn’t interested in making any sensational revelations. I wanted to show something else: that even – and especially – a philosophy that places a strong emphasis on the individual and claims that every individual thinks independently, individually and “transcendentally”, emerges within a social constellation. Paradoxically, the formulation of this somehow solipsistic philosophy took place in a completely non-solipsistic way, in a network of interconnected relationships.

Call for a mild form of Enlightenment

How relevant is the Enlightenment in 2024, 300 years after the birth of Kant? Why is it interesting to study the Enlightenment today?You don’t need to be especially astute to see that the achievements of the Enlightenment are under massive attack everywhere in the world. Trumpism as a global movement, the rise of populism, authoritarian movements, identitarian thinking – these all represent direct attacks on universal reason.

On the one hand, I think a post-colonial, feminist, deconstructivist critique of certain Enlightenment ideas is important and justified. And naturally, it is important that “the West” critically examines the history of its own racism and imperialism. On the other hand, we should not discard something good when trying to eliminate something bad. The question is how we can advocate, in an appropriate manner, a mild form of enlightenment, a form of universalism that is communicative rather than “radical”. How can we prevent enlightenment from coming across as being a kind of “top-down rational imperialism”? This would have to be a less rigorous, more playful, yet still consistent form of enlightenment. How do we formulate an idea of enlightenment that acknowledges its own shadows, ghosts, unresolved questions and ambivalences, yet still defends the dignity of all people? This is the challenge.

“The Philosopher’s Servant”

Felix Heidenreich’s novel “The Philosopher’s Servant”, marking Kant’s anniversary year of 2024, is published by Wallstein-Verlag. In this captivating novel, companions of Immanuel Kant tell their stories from different perspectives: his footman Martin Lampe, his secretary Ehregott Wasianski, the merchant Joseph Green and the philosopher himself. His footman Lampe is not as foolish as he initially seems, Wasianski disapproves of Kant’s plans to marry and Green has to provide insightful comments on Kant’s philosophical writings alongside his duties as a merchant. About “The Philosopher’s Servant