Thomas Meyer Action as Freedom

Hannah Arendt, perhaps the most influential thinker of the 20th century, died 50 years ago. In an interview, philosophy professor Thomas Meyer reveals why her ideas remain so relevant today and how her years in exile shaped this thinking.

Mr Meyer, you have published two biographies of Hannah Arendt, one of which is considered a new standard work. You’re also releasing a new scholarly edition of her writings. What sparked your fascination with the philosopher and political theorist?My interest in Hannah Arendt was sparked almost by chance. The publishing house dtv asked me if I wanted to publish an essay from the archives. The German title was Die Freiheit, frei zu sein (The Freedom to Be Free). I thought the timing was perfect. After it was released in 2018, sales immediately skyrocketed. Another key moment came when Bayerische Rundfunk and other broadcasters asked me what philosophy could contribute in response to the “refugee crisis”. That’s when I republished Arendt’s We Refugees with Reclam, and this essay also proved to be highly relevant to the issues of that time.

Then I started researching for a biography, and I soon realised that the state of the texts was, to put it mildly, quite poor. I agreed with Piper Verlag on a 12-volume edition of Arendt’s German writings. A 13th volume was added, containing two texts I had discovered, in which Arendt engages with Palestine and Israel.

That sounds highly topical. Does this apply specifically to these texts, or to Arendt’s thinking in general?

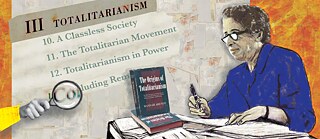

I’m not someone who immediately resorts to a quote from Hannah Arendt as soon as they encounter a problem and thinks everything has then been said. Nevertheless, I can say that, alongside the texts already mentioned, reading The Origins of Totalitarianism, first published in German in 1955, can clearly highlight the dangers inherent in the gradual slide of democracies into authoritarian regimes. It illustrates how people can essentially be “moulded”, and how these creeping, then suddenly radicalising processes develop. In this regard, Arendt is an exceptionally perceptive observer.

Arendt was not only a thinker of catastrophes.

Can you be more specific?

Well, imagine how Arendt would react after the various meetings between Selenskyj, Trump and the European heads of state. At the moment, everything is vague; we only have statements of intent. But, as Arendt says, mere declarations do not accomplish anything. What is needed is a binding contractual framework, in which rights and obligations are assumed, enabling accountability among parties. In this sense, she was also a very legally minded person.

In your major Arendt biography, you focus primarily on her time in France and America, where she lived in exile as a Jew in the 1930s and 1940s. During this period, she was politically active and evidently helped more than 100 Jewish children escape. Interestingly, this aspect of her life seems to have received very little attention. Why do you think that is?

First of all, this is because philosophers and political theorists generally aren’t interested in archives. The second point is that the great Hannah Arendt focused on the major problems of the world. The idea that she cooked lunch for children, spent hours on the phone and tried to organise visas for people – this was difficult to imagine. It was also difficult to imagine that she spent many years in the US working as a freelance writer under rather precarious conditions. All of these aspects were automatically overlooked when people thought about the great Hannah Arendt.

There is no thinking that is not nourished by experience.

I often refer to Arendt’s remark that there is no thinking that is not nourished by experience. What she experienced in France was that anyone without a passport had no rights and, in effect, did not exist. She came to understand that our very humanity is bound up to our legal status. And she was constantly surrounded by refugees who no longer had any rights. One famous chapter in The Origins of Totalitarianism on the right to have rights can be seen as arising directly from these experiences.

And she worked for Jewish refugee organisations?

In Paris, yes. In the US, she worked for Jewish Cultural Reconstruction, Inc., an organisation dedicated to rescuing Jewish cultural artifacts and libraries. She worked there for another ten years, eventually taking on a leadership role. In that capacity, she returned to Europe for the first time in 1949 and, in early 1950, to Germany.

It seems that for a long time, she didn’t speak about her years in exile – until the legendary TV interview with Günter Gaus in October 1964.

Even her circle of friends, as far as we can tell from the letters, knew nothing about certain periods of her life. In her interview with Gaus, she recounted them almost like an adventure story: we took care of the children, organised visas for them, and so on.

But no one followed up on any of this?

Elisabeth Young-Bruehl mentions a few things in her first biography. I know of researchers who eventually gave up the search. I wouldn’t have found anything either if I hadn’t come across a clue in an archive that led me to Jerusalem. This is where a friend and I discovered the documents. We will be publishing them next year. They include letters and papers, reports, lists of names – with details such as the children’s health status, telegrams, but also vivid reports on the situation in Germany and France.

Let’s return to the famous interview with Gaus, which, as you write, now has something of a cult status. Why is this?

Even the newspaper reviews were enthusiastic. Never before had a Jewish woman spoken in such a way on German TV. She told her life story on her own terms, confidently, with clarity, but also with a certain detachment. This immediately struck viewers. The interview later went on to win several Grimme Awards.

Arendt’s voice likely played a role as well. In your book, you refer to the “Arendt sound”. But it was also the way she sat – self-assured, the image of the smoking intellectual. This was a posture typically associated only with men.

Yes, absolutely. She was completely emancipated. And I think this combination both fascinated and unsettled people.

From today’s perspective, which of Arendt’s works would you consider the most important? And which piece would you recommend as a starting point?

I think the most important publication is still The Origins of Totalitarianism. But you can’t just hand it to someone. Our edition of the book is over 1,000 pages long. As a starting point, I’d recommend her book on Rahel Varnhagen. I think it’s the most accessible. It explores the life of a German Jewish woman in the Romantic era. Otherwise, in the collections where we published her lectures and essays, some texts are clearly aimed at a scholarly audience, but there are also pieces like We Refugees, where she explores issues such as truth and lies in politics. In short, Hannah Arendt offers both: highly complex scholarly essays and more accessible texts on general political issues that are just as relevant today as they were 50 or 60 years ago.