A Critical View The Shortcomings in Political Theory

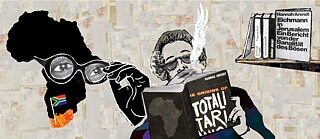

Illustration: © Eléonore Roedel

In a time marked by the resurgence of white nationalism, Hannah Arendt’s work on totalitarianism is frequently invoked as a guide to our socio-political crises. From South Africa's perspective, however, reading her work reveals a fundamental paradox.

About thirty years into South Africa’s democracy, a curious gathering takes place in the Oval Office of the White House in Washington, D.C. South African president Cyril Ramaphosa and US president Donald Trump meet to `strengthen bilateral ties`. What follows is more a sensationalist, political theatre than serious diplomatic talks. The president of the United States, thumbing through tabloid clippings as if they were state dossiers, punctuates a bizarre montage with a litany: “Death. Death. Death. Death.” Headlines flash: South Africa’s White Genocide.For the rest of the week, international media mulls the meaning of this meeting. Fact checks abound: There is no white genocide, they declare, just rampant inequality and crime.

Here, South Africa is not a sovereign nation-state negotiating questions of trade or diplomacy. It is staged, instead, as a parable of racial apocalypse. The headlines do not document South Africa so much as they conjure a fantasy of white victimhood – an inversion in which the beneficiaries of historical dispossession imagine themselves as its targets.

A strange interdependence of opposites

Since the first Dutch East India Company vessels attempted to round and later occupy the Cape in the mid-seventeenth century, the territory now known as South Africa has held an outsized and enduring place in the global racial imaginary.The country has served, at various historical moments, as both a paradigmatic site of imperial conquest and racial domination, as well as a symbolic crucible for liberationist dreams and solidarities. Its contours, shaped as much by European colonial cartographies as by African intellectual, cultural, and political productions, extend far beyond its physical borders, reaching into the speculative terrains of those who imagine, contest, and reconfigure racial order.

For decades, those unsettled by the prospect or reality of Black majority rule have mobilised the imagery of the death camp as a rhetorical device, reframing shifts in land ownership or state policy as existential threats to white survival. This metaphorical transposition of European atrocity memory into the South African context, transforming the post-apartheid state into a spectral perpetrator, constitutes what Achille Mbembe might call a colonial inversion: a reversal in which the beneficiaries of historic racial domination reimagine themselves as its victims.

At the dark heart of this rhetorical operation lies a profound absurdity, one reminiscent of Hannah Arendt’s reflections on totalitarianism and the “strange interdependence of opposites” it engenders. Here, the absurd emerges in the juxtaposition of mutually incompatible realities: the myth of white victimhood alongside the continued structural dominance of white capital; the invocation of humanitarian suffering by those who, in many cases, preside over said conditions of exploitation; the call for global sympathy by those whose privilege was historically secured through systemic violence. It is these tensions, where fact and fabrication, grievance and domination, atrocity and impunity circulate together, that mark this current political climate.

Arendt’s reproduction of colonial imagery

In The Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt directs sharp criticism at the “race fanatics of South Africa,” casting their obsession with racial order as symptomatic of an ideological degeneration of politics into brute domination. She identifies the parallels between South African apartheid and the exterminationist logics of Nazism. But while she positions herself critically against Apartheid’s crude racial authoritarianism, Arendt also reproduces, with little critical distance, the very civilisational hierarchies that underpinned it.Consider her claim that:

“Race was the emergency explanation of human beings whom no European or civilised man could understand and whose humanity so frightened and humiliated the immigrants that they no longer cared to belong to the same human species. Race was the Boers' answer to the overwhelming monstrosity of Africa – a whole continent populated and overpopulated by savages – an explanation of the madness which grasped and illuminated them like ‘a flash of lightning in a serene sky: ‘Exterminate all the brutes.’”

Here, the conceptual scaffolding of Arendt’s critique rests on the reanimation of colonial tropes. Black Africans are cast as “savages,” their presence reduced to “the monstrosity of Africa,” their humanity visible only as a problem for Europeans. Race is presented as a kind of ideological emergency measure, but the very terms through which Arendt renders this “emergency” are saturated with white colonial fantasy.

Elsewhere, she elaborates:

“The Boers were the first European group to become completely alienated from the pride which Western man felt in living in a world created and fabricated by himself… Lazy and unproductive, they agreed to vegetate on essentially the same level as the black tribes had vegetated for thousands of years… The great horror… was stimulated by precisely this touch of inhumanity among human beings who apparently were as much a part of nature as wild animals… When the Boers… decided to use these savages as though they were just another form of animal life… they embarked upon a process which could only end with their own degeneration… from whom in the end they would differ only in the color of their skin.”

Black Africans are described as “vegetating” in a static, prehistorical time; their relationship to the land is collapsed into the idiom of “wild animals”; and the ultimate horror is narrated not as the violence of colonial domination, but as the prospect of white degeneration. The “degeneration” she fears is not the collapse of an unjust racial order, but the dissolution of racial distinction itself, framed as a civilisational decline.

What emerges, then, is a paradox. Arendt denounces segregationist racism as “fanaticism” while simultaneously reproducing the colonial imaginary in which Black existence is figured as stasis, opacity, and nature. Her horror is not at the dehumanisation of the colonised, but at the possibility that whites might collapse into the same category of animality.

Arendt and Mandela

This paradox acquires flesh in a smaller, more intimate drama; the Balzan episode. As David D. Kim recounts in his three-part essay Why Didn’t Hannah Arendt Nominate Nelson Mandela for the Balzan Prize?, the story begins in 1963, a year of turbulence for Arendt. She had just returned from a brief reprieve in Europe to a firestorm over Eichmann in Jerusalem. Across the Atlantic, Medgar Evers had been murdered in Mississippi; in South Africa, the apartheid state responded to Sharpeville with new repressive laws and mass arrests.At the same moment, her old teacher Karl Jaspers, serving on the jury of the Balzan Prize for Humanity, Peace, and Fraternity among Peoples, asked her for recommendations. The prize, newly established and ambitious in scope, sought to reward “efforts on behalf of peace between the races.”

Arendt took the request seriously. She arranged a confidential meeting in Paris with the South African writer Dan Jacobson, who provided her with dossiers on possible candidates. Three names surfaced: Alan Paton, the liberal author of Cry, the Beloved Country; Trevor Huddleston, the English Anglican bishop who had stood with Black residents of Sophiatown against forced removals; and Nelson Mandela, then in prison. Jacobson sent Arendt Mandela’s speeches from the Treason Trial, complete with handwritten corrections, along with biographical notes on his legal work with Oliver Tambo and his leadership in the ANC Youth League.

One might imagine that Arendt, who had already diagnosed South Africa as a “race society” in The Origins of Totalitarianism, would seize the opportunity to recommend Mandela, the figure who most visibly embodied resistance to that system, and who was paying for it with his freedom. But she did not. On 9 August 1963, Arendt forwarded Jacobson’s material to Jaspers with her own biographical summaries. She listed “TREVOR HUDDLESTON” first, praising his Christian witness, his commitment to nonviolence, and his popularity among Black South Africans. Mandela, she noted briefly, was a lawyer, a “Negro,” a descendant of “tribal chiefs.” He had organised strikes, lived underground, been betrayed by an informer, and given “a very outstanding speech” at his trial. But she relegated him to second place.

Kim shows how telling this refusal is. Arendt had not read Mandela’s speeches closely, nor did she include Jacobson’s fuller biography when passing materials along. She emphasised Huddleston’s charisma, his moral clarity, and his European recognisability, while diminishing Mandela to a few cursory lines shadowed by references to “terror.” For a prize meant to recognise “peace between the races,” Arendt could not, or would not, see a Black revolutionary who had turned toward armed struggle as a figure of peace. Her political imagination required a moral witness who fit within the frame of civilisation; Huddleston could embody that role, Mandela could not.

The Arendtian Paradox

The paradox resurfaces: Arendt could name race as the ideological fanaticism of the Boers, but in her judgments, she re-enacted the hierarchy she sought to criticise. She could support the struggle against apartheid, but only when it was mediated through a white figure of conscience whose authority was legible to Europe. She could recognise Mandela’s suffering, but not his politics. What terrified her was not the long durée of racial domination, but the spectre of revolutionary violence, the very collapse of boundaries between politics and war that she saw as the undoing of civilisation itself.In the Balzan episode, then, the civilisational hierarchy of her writings is quietly performed again. Black resistance is cast as excessive, “fanatical,” tainted by violence; white solidarity is elevated as the authentic bearer of universal human values. If, as Kim argues, Arendt’s decision has remained overlooked because it sits outside her published corpus, it nonetheless crystallises the structure of her thought: a critique of racism that stops short at the threshold of Black political action, a denunciation of “fanaticism” that cannot disentangle itself from the colonial imaginary.