To what extent does external dependence on the former imperial powers hamper democracy? Nicolás Lynch Gamero sheds light on the situation in Latin America.

Democracy as a political system has been debated in Latin America amid tension between those who believe it to be, without embarrassment, an imported system and those who insist on seeking autochthonous roots for its flourishing. The former have written constitutions in the last two hundred years that have generated an egalitarian rhetoric about an acutely unequal reality, often leading to even greater inequality. The latter have been determined to find the roots of democratisation in the social and political processes of the region, questioning the democracies in name only that have had limited - and even negative - political effects on the political participation and representation of the population.

-

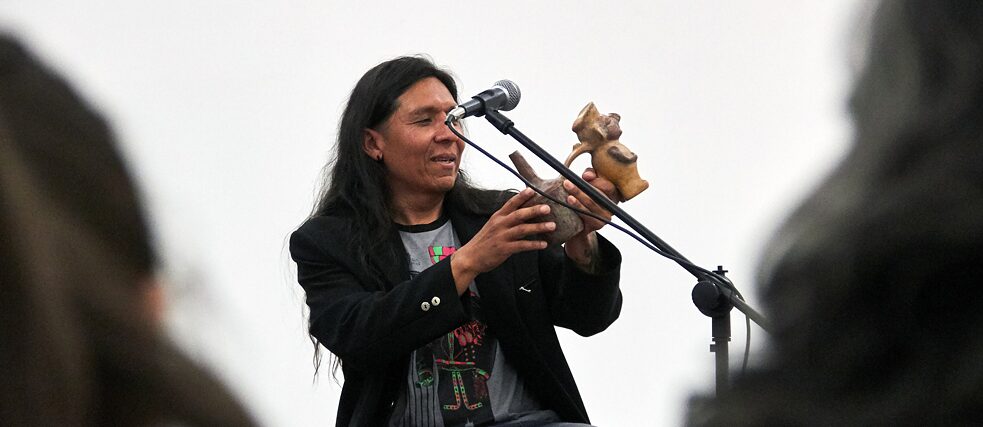

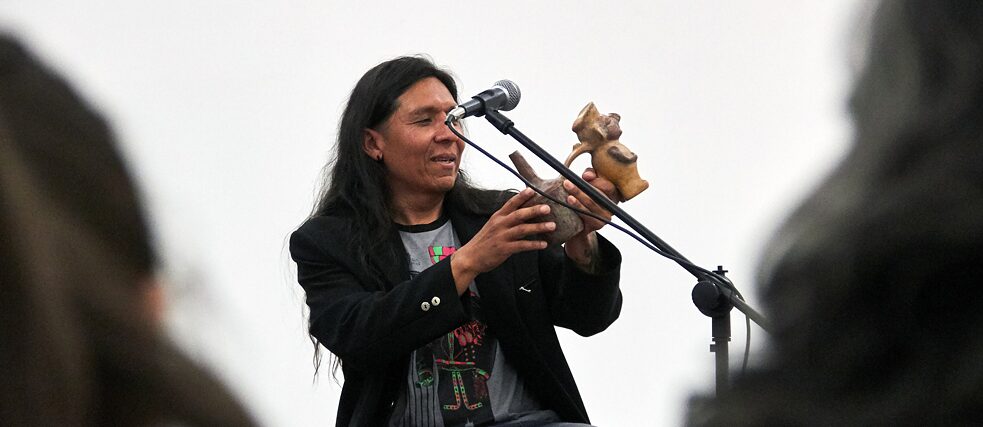

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Zsófia Puszt

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Zsófia Puszt

Performance of Emilio Urbay Zevallos during the 1st HumboldtHuaca Workshop, Berlin, 11 May 2019.

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Pablo Santacana

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Pablo Santacana

Lecture by Belén Olivera Huamán during the 3rd HumboldtHuaca Workshop, Berlin, 18 May 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Oscar Moreno

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Oscar Moreno

Collective dancing hosted by Luz Zenaida Hualpa Garcia during the 3rd HumboldtHuaca Workshop, Berlin, 14 June 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

HumboldtHuaca, ritual en resistencia, Museumsinsel Berlin, 31 October 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

HumboldtHuaca, ritual en resistencia, Museumsinsel Berlin, 31 October 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Lijung Choi.

HumboldtHuaca, ritual en resistencia, Museumsinsel Berlin, 31 October 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Barbara Lehnebach

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Barbara Lehnebach

HumboldtHuaca, ritual en resistencia, Museumsinsel Berlin, 31 October 2019

-

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Daniela Zambrano Almidon

© HumboldtHuaca – a project by Daniela Zambrano Almidon und Pablo Santacana. Image: Daniela Zambrano Almidon

HumboldtHuaca, field research in the community of Chuquitanta, Lima, October 2020

A fundamental explanatory element for this tension is colonial inheritance. Initially, this is seen in the maintaining of the economic and social structures that had been dragging on since colonial times and which conditioned the creole elite, organised as an oligarchy, to repeat political apparatuses of domination that allowed them to continue with the exclusion and exploitation of the mestizo and indigenous majorities. At a later stage, it is the prolongation of colonial dependence on the neo-colonial relationship with new foreign powers, mainly Great Britain and later the United States, who organised production, especially the extraction of raw materials for the global market, in accordance with their economic interests. This neo-colonial domination, while giving way to an initial construction and centralisation of the state apparatus, continued with the political order that excludes the majority in each country.

Persistent Colonial Dependence

In the 1920s, José Carlos Mariátegui pointed out that, for the Peruvian case, neo-colonial dependence was defined by the needs of the oligarchy, foreign investment in export enclaves and the exploitation of the indigenous population in large pre-capitalist

haciendas. A situation that was certainly far from the equality of status and universal suffrage that are indispensable for the establishment of a minimally democratic political regime.

“The difficulties of democracy in Latin America are therefore inextricably linked to colonial inheritance, which prevents countries from building themselves up with autonomy.”

It was not until the capitalist crisis of 1930, which caused serious damage to the extractivist economy, that the first anti-oligarchic reactions occurred within the excluded sectors of the population. Different types of coalitions were formed in various countries, raising issues of social justice, development and national sovereignty and producing what in political sociology would later be called the national-populist movements. The anti-oligarchic reaction established from the outset that in order to include the majority of the population in a democratic order, it was necessary to defeat the alliance between the local elite and the foreign imperial power that sustained them. The programme would thus be anti-imperialist, as stated in an early book by Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre entitled

Anti-imperialism and the APRA which resonated in the furthest areas of the region with Lázaro Cárdenas in Mexico and Juan Domingo Perón in Argentina. Neo-colonial dependency was seen as what united the elite and the imperial power to prevent democracy as well as any attempts to end that inheritance and democratise Latin America.

Theory of Dependence

But, beyond anti-imperialism, which was mainly a political attitude, a school of thought was generated in the region, in the second half of the 20th century, which we can generally call “the theory of dependence”. From Raúl Prebisch and the structuralism developed in the Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLAC), which established the notions of centre and periphery to locate Latin American economies, through the contributions by Fernando Henrique Cardoso and Enzo Faletto on the political dimension of dependence, and the reflections by Ruy Mauro Marini on the exploitation of labour in the periphery, to more recent theses such as those by Aníbal Quijano on the coloniality of power. We have a polyhedron in which the original anti-imperialism finds flesh and to which are added the economic, social, political and labour dimensions; as well as the situation of our indigenous peoples. The theory of dependence was therefore a very important step in updating colonial inheritance in the 20th century and pointing out more clearly the limits to establishing democracy in states with little autonomy as such.

“The dependence on and the legacy of colonial power prevent the democratisation of Latin American societies.”

Among these contributions, perhaps the one that best summarizes the situation of dependency is that of Aníbal Quijano and his thesis of the coloniality of power. Quijano points out that from the conquest to the present day, historical, social and political structures of dependency have been consolidated between our region of the world and the centres of colonial or imperial power. He further states that these structures revolve around the classification of the population based on the idea of race as the fundamental axis of colonial power and that the expansion of colonialism or imperialism develops a eurocentric perspective of knowledge. For Quijano, racial classification and the over-exploitation of labour are structurally related. Here he shares the views of José Carlos Mariátegui on the “indigenous problem” and Pablo González Casanova in his thesis on internal colonialism, as well as Ruy Mauro Marini, to point out that racial domination and class exploitation are interwoven with the phenomenon of the coloniality of power. This is why he says, following Cardoso and Faletto, that coloniality is not only a problem of external dependence, but also of internal organisation of power in our societies, where a minority heir and breeder of colonial power dominates the majority heir of the indigenous peoples. For this reason, those in charge not only exploit in a classist way but also racially despise the dominated.

“The theory of dependence was therefore a very important step in updating colonial inheritance in the 20th century and pointing out more clearly the limits to establishing democracy in states with little autonomy as such.”

The dependence on and the legacy of colonial power prevent the democratisation of Latin American societies, the consideration of the other as equal, as well as the construction of a political regime of majority participation and representation. The difficulties of democracy in Latin America are therefore inextricably linked to colonial inheritance, which prevents countries from building themselves up with autonomy, the first and fundamental condition for citizens to be able to express themselves freely and for states to be able to make their own decisions.

LITERATURE

- Cardoso, Fernando Henrique and Enzo Faletto, 1969:

Dependencia y Desarrollo en América Latina. Buenos Aires: Siglo Veintiuno editores.

- Germani, Gino, 1965:

Política y Sociedad en una época de transición. Buenos Aires: Editorial Paidós.

- González Casanova, Pablo, 1963:

Sociedad plural, colonialismo interno y desarrollo. UNESCO

- González Casanova, Pablo, 2003:

Colonialismo interno (Una redefinición). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. Instituto de Investigaciones Sociales.

- Haya de la Torre, Víctor Raúl, 1972:

El antimperialismo y el APRA. Lima: Editorial – Imprenta Amauta S.A.

- Mariátegui, José Carlos, 1970:

Siete ensayos de interpretación de la realidad peruana. Lima: Empresa Editora Amauta

- Marini, Ruy Mauro, 1973:

Dialéctica de la Dependencia. Mexico: Ediciones Era.

- Prebisch, Raúl, 1987:

Cinco etapas de mi pensamiento sobre el desarrollo. Santiago de Chile: Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

- Quijano, Aníbal 2011: “Colonialidad del poder, eurocentrismo y América Latina”, in:

La colonialidad del saber: eruocentrismo y ciencias sociales. Edgardo Lander, compiler. Buenos Aires: Ediciones Ciccus-Clacso, 2nd Edition.

0 0 Comments