Racism in Peru The Fear of Equality

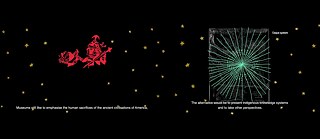

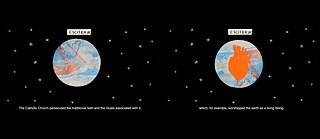

Videostill from the project “Intervention M21” (www.decolonizem21.info): The (De)Colonial Glossary, Part 1, Europe - Non-Europe | © Aliza Yanes & Santiago Calderón

Peru’s history is dominated by the discourse on mestizaje and racist practices, according to the Peruvian essayist and literary critic Marcel Velázquez Castro.

In Peru, in recent years, the debate on racism has become more frequent in the public space. On the one hand, social media converts videos or images of racial discrimination into viral content. On the other, state institutions and society have less tolerance for traditional prejudices and explicitly condemn racism.Interculturality: The New Image of the Country

Since the beginning of the 21st century and under the paradigms of multiculturalism and the politics of difference, the Peruvian State has modified its previous discourse and promoted an active recognition of social groups self-defined through culture, history and identity. This process was also the result of the political work of Afro-Peruvian and Amazonian Indigenous organisations. Interculturality is established as a communication horizon for the new national image.“The State seeks a cultural solution that does not modify power structures or social exclusions. In this way, racial hierarchies, which surge into view in times of crisis, are hidden.”

The Case of Negrita

The Alicorp company decided to change the name of its Negrita brand, associated with products for the confectionary industry. The brand had been on the national market for decades and the decision has given rise to three main interpretations: an illegitimate victory of moral indignation and an attack on tradition and commercial freedom; a positive corporate gesture by Alicorp, within a global framework of struggles for diversity and anti-racism; and a victory in the long road to decolonisation of the Afro-Peruvian imaginary.The key word in the first position is tradition; this interpretation celebrates a status quo founded on naturalised and invisible socio-racial inequality, an order that makes the enjoyment of their privileges possible. The second position is open to criticism because the corporate world that serves capital offers a supposed concern for the life and experiences of Afro-Peruvians. The third position claims the political consequence of this anti-racist event, with possible repercussions beyond the commercial and advertising sphere.

A Long History of Dominance and Exclusion

A quick review of advertising that uses Black women and men to promote its products confirms that the desire of the Afro subject is invisible; it is a matter of satisfying the demand of those who, in order to enjoy their desires, require physical work done by people of Afro descent. The figures that represent brands such as Negrita, ÑaPancha, Sibarita or others, condense, through an apparently innocent graphic codification, a long history of domination and exclusion; the naturalisation of domestic service and the kitchen as the place of Afro-Peruvian women. Furthermore, they also show the sexual desire for the Black woman and the nostalgia for the servile world of the hacienda.It is worth noting the diminutive of Negrita, which offers a simulation of affection and familiarity, but also a reduction, an infantilisation that has frequently been the norm in the representation of subordinates. It is very easy to say “negrito”, “cholito”, but very difficult to say “blanquito” or “gringuito”.

Undoubtedly, this connects seamlessly to the world of slavery, since it creates the fantasy in which you are the slave master, with the Afro woman faithfully working for you in food services, laundry and confectionery. The results of her work are mystified and appear as offerings of affection to disguise the oppression in a bygone world, with a static temporality and a rural spatiality.

Connection to the World of Slavery

Slavery was part of the private life and experience of the Limeño; the commercial advertising of slaves is foundational in the history of advertising in Peru. Until 1854, the year of the abolition of slavery, the main activity of male and female slaves in Lima was domestic service, including laundry and food preparation. Moreover, years later, aristocratic families continued to have workers of African descent as coachmen and cooks. This was seen as a sign of social distinction by the rest of society, which also wished to exercise that dominance.“The social fear of the elites is the fear of equality, of the imaginary loss of their privileged position. For this reason, they want to naturalise inequality and attribute to others the place of dirt, of disease and ugliness.”

The second episode occurred in a parliamentary campaign in 2020 in Lima, when a candidate with white features gave a mestizo candidate a bar of soap to disqualify him as a political opponent. In the modern age, a correlation is artificially constructed between decency, health, cleanliness and whiteness on the one hand; and indecency, sickness, uncleanliness and Blacks, Indigenous peoples and Asians on the other. Moreover, the theory of medical hygienism seeks to find the origin of disease in external causes; consequently, it draws an association between poverty, marginality, dirt and disease.

Soap as a Materialisation of Symbolic Colonial Violence

Without denying the practical advantages of soap, it is impossible not to see its links with colonialism, racism and hygienism. Policies of entering “civilisation” through the consumption of Western goods presupposed that dirty and non-white were synonyms, as in the classic Anglo-Saxon adverts for Pears’ soap, which accompanied British imperialism. Soap became simultaneously an emblem of modernity, a materialisation of symbolic colonial violence and a ratification of explicit symbolism. In addition, it mobilised the fantasies of civilisation, cleanliness and whitening among “brown” social sectors. From a different angle, medical science and hygienist ideas confirm the triumph of soap. Consequently, since the mid 19th century, a correlation is established between beauty, white and decent and thus the legitimisation of the racial hierarchy in Peru is strengthened.The social fear of the elites is the fear of equality, of the imaginary loss of their privileged position. For this reason, they want to naturalise inequality and attribute to others the place of dirt, of disease and ugliness.

0 0 Comments