The “Blue Rider Post” Cameroon’s Right to Cultural Objects

During the colonial era of the German Empire, officer and commander Max von Stetten brought over 200 artefacts from Cameroon to Munich. They have been housed in Munich’s Museum Fünf Kontinente for more than a century rather than in their original home. The gaps left in the origin country by their absence are being investigated by researchers from Cameroon and Germany within the scope of a project entitled “The ‘Blue Rider Post’ and the Max von Stetten Collection (1893 - 1896) from Cameroon in the Museum Fünf Kontinente, Munich”.

“The initial intention was to gather information on the artefacts that were not in the museum,” says Professor Albert Gouaffo, who has headed the project in Cameroon since the end of 2019. He has collaborated with other Cameroonian research colleagues to find the original owners of the objects there and research their significance and context of acquisition. “Many of the societies cannot remember very much about the artefacts,” says research assistant Dr Ngome Elvis Nkome.One thing that’s especially important with this research project is to trace the origin societies and gain their trust. “The first thing we had to do was get to know each other, because the subject we are dealing with is very sensitive and there’s always the suspicion that we could be seen as acting as henchmen for the Europeans, and that as a result they would refuse us certain information,” says Gouaffo. “The other problem was refusal to give information not just because there was mistrust, but because they consider themselves to be experts rather than simply providers of information and for that reason they should be respected.” As well as gaining their trust, there were a few other obstacles to overcome in order to find out more about the artefacts. The country of Cameroon is divided by a language border. The population is split into two parts – one of which is anglophone or English-speaking, the other is francophone – French-speaking. At the moment a civil war caused by a separatist movement is under way in the anglophone region. The resulting unrest has consequences for the project: for one thing it’s too dangerous to visit certain regions from which some objects might originate. And as Dr Nkome, who comes from the anglophone territory himself, explains: “The internal dynamics in the anglophone region have made it harder to find key informants who could have provided us with detailed information about the collection we’re studying.”

Absent Objects

Furthermore a key role is played by the joint venture with Museum Fünf Kontinente in Munich and the information held there. Some of the information on file was wrong, locations were often muddled up or incorrectly labelled here. “The collectors weren’t ethnologists,” says Prof. Gouaffo. Moreover the artefacts in the Max von Stetten collection are staying in the Munich museum for the duration of the research project. As a result the research colleagues in Cameroon only have access to photos, which complicates their work with informants. “If the object were physically present at the location they might be able to touch it, which would allow them to draw analogies based on the material from which the artefact was made,” says Dr Nkome.Another problem is the long absence of the artefacts from their origin societies. These artefacts have been in Germany for more than a century. The origin societies have changed over time, and consequently their meaning and intended use cannot always be determined – for example because religious beliefs have changed, so that sacred objects from a religious practice were no longer desired or needed and thus were forgotten.

The “Blue-Rider-Post”

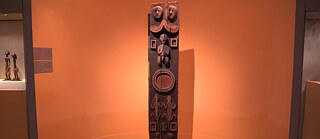

The most notable object in the collection is a piece known as the “Blue Rider Post”. The life-sized wooden block is decorated with a variety of carved patterns, including geometric forms and human faces, and it is currently exhibited in the African collection at the museum in Munich. Neither its purpose nor its precise origin society are known yet. The wooden block is decorated with carvings from top to bottom.

| Tom Kimmig @ Goethe-Institut

Although the researchers – who include Yrine Matchinda, Lucie Mbogni Nankeng and Professor Joseph Ebune as well as Gouaffo and Nkome – believe that it comes from the forested regions in the west of Cameroon, an area within today’s anglophone territory, they also think a link exists with the grasslands in the north and northwest of the country. “The artefact was actually made by a craftsman from the grasslands, but they used a material from the forest. And the symbols or text depicted on it were also illustrated in colour by the people from the forests, and the connotations were different,” says Prof. Gouaffo.

The wooden block is decorated with carvings from top to bottom.

| Tom Kimmig @ Goethe-Institut

Although the researchers – who include Yrine Matchinda, Lucie Mbogni Nankeng and Professor Joseph Ebune as well as Gouaffo and Nkome – believe that it comes from the forested regions in the west of Cameroon, an area within today’s anglophone territory, they also think a link exists with the grasslands in the north and northwest of the country. “The artefact was actually made by a craftsman from the grasslands, but they used a material from the forest. And the symbols or text depicted on it were also illustrated in colour by the people from the forests, and the connotations were different,” says Prof. Gouaffo.The researcher assumes the origin to be the Miang region in western Cameroon, explaining his hypothesis as follows: “The people from Miang, Bakundu, Mbo, Bakossi and Abo or Miangese are well-known for carving statues as tall as a person.”

There is also some conjecture about the original use of the Blue Rider Post too: “Most informants refer to such objects as doorposts or doorframes,” says Dr Nkome. In the grasslands, specifically in the Mankon community, objects like this are placed at the entrances of palaces or shrines. Prof. Gouaffo doesn’t think the wooden block is a simple doorpost: “It’s far too heavy for that. The ‘Blue Rider Post’ is a spiritual object. According to the oral tradition, the object was installed in a religious building like a statue. Hats, chains, bags or skeletons might have been hung on it. Secret societies like the ‘Losango’ used the statue to carry out certain rituals, for example cleansing the village of evil spirits.”

“In the African context there is a need for different terminology, because a coerced purchase is not the same as going to a shop and buying something in Germany.”

The acquisition contexts of all objects should generally be viewed critically: “In the African context there is a need for different terminology, because a coerced purchase is not the same as going to a shop and buying something in Germany,” explains Prof. Gouaffo. “A gift is not a gift in the true sense of the word, because the Indigenous person is acquiescing to power and demonstrating their vassalage to the new ruler through the act of presenting the gift,” continues the researcher.

Even without full clarification of its purpose or knowledge of its origin society, objects like the “Blue Rider Post” have an important connection with Cameroon. “Any object for which no clear-cut information about the original owners exists should be kept in the national museum that houses the entire national heritage of that country,” stresses Dr Nkome. “For me it’s important that provenance research is linked with restitution and the question of authorship is clarified,” emphasises Prof. Gouaffo.

“Whether the people [in Cameroon] identify with it or not – the fact is that the objects once belonged to them. And the main challenge now is how to shape the future,” continues Prof. Gouaffo. “It calls for a certain degree of preparation on the part of the country destined to receive the artefacts,” says Dr Nkome. Technical, financial and material logistics have to be put in place first ready for restitution.

Once the research project finishes in January 2022, the plan is to collate the findings from the museum researchers and in the origin country of Cameroon for the first time and present them to the public.