Beyond the comics of Marvel and DC, in 1970s Germany, there was an illustrated world that still transports the boomer generation in particular into nostalgic fits of rapture today. Even kids from the decades that followed still fondly look back on the comic book series of their childhood.

Singer-songwriter Franz Josef Degenhardt satirised the conservative bourgeoisie of the 1950s and 1960s in his song Schmuddelkinder with the lines “Don’t play with the Schmuddelkinder (filthy kids), don’t sing their songs.” He may as well have added: “And don’t read any Schmuddelhefte!” (filthy rags). Because that is exactly what comics were in the eyes of the vast majority of adults back then. Astonishingly, the classic penny dreadfuls with their trivial content enjoyed a better image: At least you had to actually read those, and not just look at the pictures. Even publisher Gustav Lübbe, who earned millions with publications both illustrated and not, considered comics “rubbish literature”.

The Name Is Mouse. Mickey Mouse.

Which makes it even more surprising that, since the early days of the Federal Republic of Germany, many publishers have dared to fight this prejudice and popularise comics as an art form in Germany with annually increasing print runs. It was still never quite as popular here as in France, Belgium and the USA with all their classics: Asterix, Tintin, the Marvel and DC comics (Superman, Spiderman, Batman, etc.). The most popular and successful at first was Walt Disney’s Mickey Mouse. The magazine was published monthly from 1951, and weekly from 1957. At that time, 300,000 copies of each issue were printed, and circulation continued to rise until the late 1980s, reaching almost one million in 1990. Today, there are just over 60,000. The heyday of comic books ended with the rise of electronic media – it is the purview of the boomer and Gen X generation, those born between 1950 and 1970.

Rolf Kauka’s Fix und Foxi magazine always followed along in the slipstream of the powerful American film and media company Disney. The stories with the two bright red foxes appeared from 1953 onwards. In 1956, the print run exceeded 100,000 copies for the first time, and from 1957 the magazine appeared weekly, with 300 million copies printed by 1995. Both Mickey Mouse and Fix und Foxi are “funnies”, i.e. funny stories with colourful pictures and speech bubbles. The drawings have few details and are deliberately not realistic.

Serial Readers for 50 Years

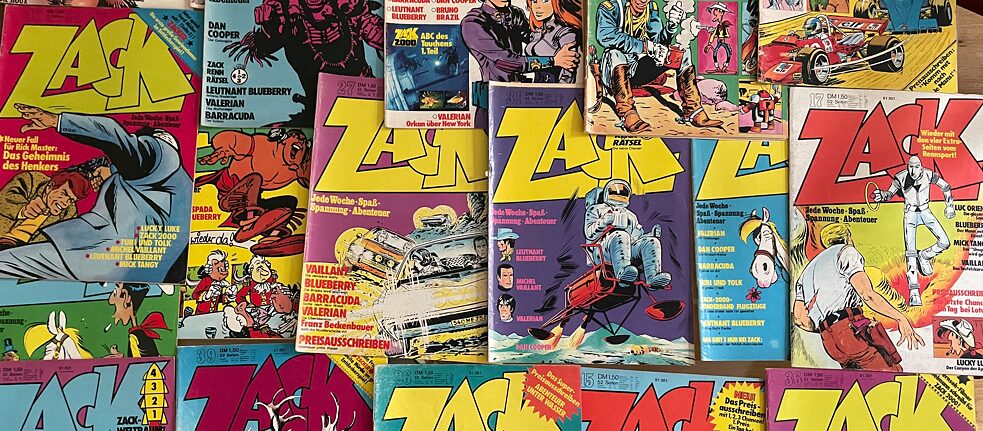

Too old for stories from Duckburg? For 50 years now, the ZACK publishing house has been serving mostly male adolescents with comic book heroes of all kinds.

| Photo (detail): picture alliance/dpa/dpa-Zentralbild/Christof Bock

But what if you felt too old for funny stories from Duckburg or a Gallic village and action, suspense, adventure were more your speed? From the late 1960s onward, German boys – who were almost exclusively the buyers and readers of these magazines – were enticed by more and more material in news agents and newsstands. A golden age had begun.

Too old for stories from Duckburg? For 50 years now, the ZACK publishing house has been serving mostly male adolescents with comic book heroes of all kinds.

| Photo (detail): picture alliance/dpa/dpa-Zentralbild/Christof Bock

But what if you felt too old for funny stories from Duckburg or a Gallic village and action, suspense, adventure were more your speed? From the late 1960s onward, German boys – who were almost exclusively the buyers and readers of these magazines – were enticed by more and more material in news agents and newsstands. A golden age had begun.

It is now fifty years since Koralle Verlag’s Zack magazine first appeared, turning Thursday into the most important day of the week for many boys. Zack worked with serialized stories, and if you wanted to see how a tale ended, you often had to buy a series of issues over several months. A wide variety of genres and drawing styles were featured on the 50 weekly, and later fortnightly pages. Most, though, were high-profile series, which even then were often published in France and Belgium as hardcover graphic novels or bandes dessinées.

Between 1972 and 1980, Zack always featured funnies like Lucky Luke, Cubitus, Pittje Pit, and Umpah-Pah, alternating with the classics of Franco-Belgian comic art known as “realistics” with settings drawn in great detail and in the genres of Western (Lieutenant Blueberry, Comanche), science fiction (Luc Orient, Valerian), and crime (Rick Master, Bruno Brazil). Even the high-brow comic Tintin by Hergé made a brief appearance in Zack, but this was an exception: Hergé and Gosicnny/Uderzo (Asterix) were maintained by their publishers, Carlsen and Ehapa, in comparatively high-priced, large-format and four-colour volumes. After all, Koralle Verlag sold 450,000 copies of Zack every week on its best days.

Comic Top Dog

Something for everyone – the Bastei comics served a wide range of preferences among their readership

| Photo (detail): alle © Bastei Lübbe

But Zack was never real competition for the true top dog on the German comics market who, by the mid-1960s, was synonymous with comics: Bastei magazines. In 1953, publisher Gustav Lübbe took over the small Bastei publishing house and had created a young adult editorial department by the end of the 1950s. The success story began with comics like Felix and Bessy (almost 1,000 issues between 1965 and 1985) with print runs in the millions, and the publishing house invented many new heroes as well. These included Lasso (almost 650 issues between 1965 and 1985), Wastl (1968 to 1972), Roy Tiger (1968 to 1970), Der rote Korsar (The Red Corsair, 1970/71), Phantom (1974 to 1983), Kung Fu (1975 to 1981), and Robin Hood (1973 to 1977). There were also comics like Biene Maja (Maya the Bee) and Nils Holgerson aimed at a younger demographic.

Something for everyone – the Bastei comics served a wide range of preferences among their readership

| Photo (detail): alle © Bastei Lübbe

But Zack was never real competition for the true top dog on the German comics market who, by the mid-1960s, was synonymous with comics: Bastei magazines. In 1953, publisher Gustav Lübbe took over the small Bastei publishing house and had created a young adult editorial department by the end of the 1950s. The success story began with comics like Felix and Bessy (almost 1,000 issues between 1965 and 1985) with print runs in the millions, and the publishing house invented many new heroes as well. These included Lasso (almost 650 issues between 1965 and 1985), Wastl (1968 to 1972), Roy Tiger (1968 to 1970), Der rote Korsar (The Red Corsair, 1970/71), Phantom (1974 to 1983), Kung Fu (1975 to 1981), and Robin Hood (1973 to 1977). There were also comics like Biene Maja (Maya the Bee) and Nils Holgerson aimed at a younger demographic.

Along with Gespenstergeschichten (Ghost Stories, more than 1,600 issues between 1974 and 2006), the western series Silberpfeil (Silver Arrow) was a key sales driver, with 768 issues between 1970 and 1988. The stories about the young Kiowa chief and his white blood brother Falk, the girl Moonchild and cantankerous trappers Jed and Harry appealed to German Winnetou fans, not really surprising considering they clearly borrowed liberally from Karl May’s cast of characters. They were produced by the studio of Belgian cartoonist Frank Sels, described at the time as “the fastest comic artist” in Europe, as he and his team could create an entire issue a week. Borrowing from successful predecessors was one of Bastei comics’ recipes for success. The Lassie movie (1943) and American TV series (1954) were the obvious inspiration for the Bessy series, which Belgian comic artist Willy Vandersteen’s studio (where Frank Sels started his career) had created in the mid-1950s.

Boys born in the 1950 to 1970 baby boom, who spent their pocket money at the kiosk, traded their comics, and hoarded them like treasures back then, have become men in their prime who now spend a lot of money on well-preserved copies at swap and collectors’ conventions. Individual issues of the Silberpfeil series, for example, can fetch tens of thousands of euros. Many well-preserved copies do not sell for under 1,000 euros, and collectors are willing to pay a lot for the paper memories of their youth. But attics and cellars are also still full of comics. It is tempting pick up and start leafing through every time you move house: You simply cannot bring yourself to throw away that magical paper.

January 2023