On his 100th birthday, we are honouring Ernst Jandl, who became known above all for his experimental poetry. His poems were many things: political, funny, drastic, melancholy. And nobody could recite them as well as Jandl himself.

1 August 1925: Ernst Jandl is born in Vienna. He also died there on 9 June 2000. He became famous for his poems, in which he experimented in many different directions. He wrote Concrete Poetry, in which language itself is the purpose and subject of the poem, Visual Poetry, in which the visual representation of the text takes centre stage, and he wrote sound poems such as schtzngrmm (1957), a spoken poem that only reveals its content when spoken. Fellow writer Helmut Heißenbüttel (1921-1996) described Jandl as "one of the first authors whose fame was not founded in books, but in the spoken word ".Jandl wrote in a deliberately pared-down language orientated towards everyday usage. In his legendary Frankfurt Poetry Lectures in 1984/85, he spoke of a "run-down language". Another stylistic feature is the almost consistent use of lower case, which he had already been using since the second half of the 1950s in order to further blur the boundaries between word classes. Jandl's work was also strongly characterised by his sense of typography, the design and arrangement of characters. His role models included Gertrude Stein and Hans Arp. Although he appreciated Stefan George as a poet, he was not influenced by him, "his view of the world and his aristocratic attitude were so alien to me".

Evergreens in a run-down language

One of the best-known poems by the Georg Büchner Prize winner (1984) is wien: heldenplatz (1962). In it, Jandl addresses the "Anschluss" (annexation) of Austria to National Socialist Germany in 1938, unmasking the crowd cheering Adolf Hitler with ambiguous neologisms that reflect the religiously and sexually charged atmosphere. The "männchenmenge" (crowd of little men) listens to the "gottelbock" (a portmanteau suggesting both ‘God’ and ‘he-goat’), the women feel "pfingstig" (a made-up word evoking Pentecostal ecstasy) when "ein knie-ender sie hirschelte" (a kneeling man copulates with them).Another evergreen is, of course, ottos mops (1963), one of Jandl's cheerful poems, at the end of which the dog vomits at his master's feet. Thanks to its slapstick-like humour and simple language, the poem is perfectly suited to being read aloud to young children. Klaus Wagenbach (1930-2021), whose publishing house released a selection of poems from Jandl's collection Laut und Luise (1966) as a record in 1968, also recognised that this record was “a hit among children”.

Favourite poems for the 100th

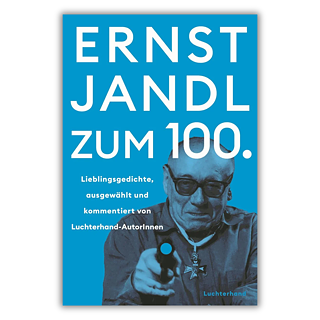

To mark the centenary, Luchterhand Literaturverlag, Jandl’s long-time publisher, has released the booklet Ernst Jandl zum 100. (Celebrating 100 Years of Ernst Jandl). In it, 20 contemporary authors each selected their favourite poem and responded to it with a short literary text. Christoph Peters chose älterndes paar. ein oratorium, a merciless and obscene poem about physical decay and its effects on love life. Peters first read the poem in his early twenties as a young lover and was shocked by this devastating love poem, but now believes that it “may have come much closer to the innermost essence of love—despite all revulsion, ugliness, and irreversible decline—than all my youthful, pretty, flawless happiness ever did.”The shortest favourite poem consists of seven repetitions of the word “nein” (no) and bears the (sub)title (beantwortung von sieben nicht gestellten fragen) (answering seven unasked questions). It was chosen by Benjamin Quaderer, who calls his response “Befragung sieben nicht gegebener Antworten“ (Questioning Seven Ungiven Answers). In it, he first reflects on the beauty and defiance of the word no (“The Ns, one might say, surround the egg like a shell. They protect the fragile interior”), before concluding—somewhat tongue-in-cheek—that with this poem, Jandl positioned himself “in a non-linguistic way” against Heidegger and his “elegiac and coercively lulling tone.”

Jandling for Everyone

Jandl’s poems can be read again and again—sometimes it is only through repeated reading that their (non)sense unfolds or a different interpretation emerges than on first reading. And many of his poems are what is often aspired to but rarely achieved: low-threshold offerings. Through his formal anarchism, Jandl encourages readers to experiment with language themselves, which led to the spread of the verb "jandln"—even at the University of Music in Würzburg, in the subject of Elementary Music Education, in the project jandln - mit Sprache spielen (jandln – playing with language). Jandl would likely have been delighted that one of the two project leaders is named Hasenhündl (it’s a compound surname, formed from the words "Hase" (hare) and "Hündl", a diminutive form of "Hund", meaning dog).To close, here is one of my favourite poems—one that probably hasn’t yet appeared on a greeting card, but who knows:

congratulations

we all wish everyone all the best:

that the targeted blow may just miss him;

that, though struck, he may not bleed visibly;

that, albeit bleeding, he may not bleed to death;

that, if bleeding to death, he may feel no pain;

that, torn apart by pain, he may find his way back to the place

where he has not yet taken the first wrong step -

we each wish all the best to everyone

Ernst Jandl zum 100. Lieblingsgedichte – ausgewählt und kommentiert von Luchterhand-AutorInnen

München: Luchterhand, 2025. 176 p.

ISBN: 978-3-630-87806-5

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

In our eLibrary Onleihe, you can also find the audiobooks Laut und Luise / hosi + anna and him hanflang war das wort, both read by Jandl himself.

München: Luchterhand, 2025. 176 p.

ISBN: 978-3-630-87806-5

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

In our eLibrary Onleihe, you can also find the audiobooks Laut und Luise / hosi + anna and him hanflang war das wort, both read by Jandl himself.

July 2025