Prostitution was illegal in the GDR. Nevertheless, the Stasi exploited women as prostitutes. Clemens Böckmann has written a documentary and harrowing novel about a woman who sells her body her entire life.

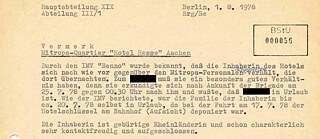

Since 1968, prostitution in the GDR was considered “anti-social behaviour” and could be punished with up to two years in prison under Section 249 of the GDR Criminal Code. The Ministry for State Security (Stasi for short) was not particularly interested in this. In the fight against the “class enemy,” women were prostituted as IM (unofficial collaborators) in order to spy on Western business travellers, for example.In his novel Was du kriegen kannst (What You Can Get), filmmaker and author Clemens Böckmann tells the life story of Uta, a sex worker who was assigned to men by the Stasi since 1971. Böckmann met the real person behind the character of Uta by chance in a bar in Leipzig in 2017. In an interview with radioeins, Böckmann explains that a long-standing exchange and a friendship that continues to this day developed between them. In the Stasi files, Uta is described as “slim”, “very intelligent, sometimes also very cunning”, “crazy about men” and a heavy drinker.

Longing for an Exciting Life

The title of the book reflects the advice of a Stasi liaison officer. “Get what you can, comrade,” he says to Uta. And that's what she does. She doesn't want to lead a boring life as a furniture saleswoman at the Zwickau consumer cooperative, but longs for a different life, for more adventure and luxury – and that also means more Western goods and Western currency, be it Deutschmarks, American dollars, Austrian schillings or Swiss francs. As “IM Anna”, an informant for the Stasi, she gets to enjoy all of that. But she will pay a high price for it.Uta travels extensively, often to the trade fair city of Leipzig, but also to Prague, where she earns a lot of money, frequently together with her friend Sabine: “In four days, the two of them earn over 2,000 German marks, plus smaller amounts in crowns, schillings and Swiss francs.” Uta has to reinvest part of her earnings: she bribes hotel employees to continue to gain access to the foyers and hotel bars. The sick notes that the women sometimes need for their trips are not free either. Sabine knows a doctor who, in return for his favours, “demands new sexual practices from her to an extent that she finds difficult to put into words.”

They'll Never Leave Me Alone Again

Uta's family life also suffers as a result of her work as an informant. When she started working for the Stasi, she was already a divorced woman with a young son. She repeatedly neglects him. When she goes out to various bars in the evenings, she leaves the key with neighbours. If she is away for several days, her parents from the Ore Mountains (Erzgebirge) step in. Looking back, she admits about her relationship with her child: “But, yes, I often left him alone. I was also a woman and wanted to experience things ... I'm just very sorry about that today.”Even after she stops working for the Stasi, Uta continues to prostitute herself. She is an alcoholic, a broken woman, and the Stasi does not leave her alone, but instead pursues a policy of “psychological destabilisation” in accordance with the catalogue of measures set out in the notorious MfS Directive No. 1/76. This leads Uta to attempt suicide:

Once I realised that they would never leave me alone again, I no longer wanted to live.

A Milestone in Documentary Literature

The textual diversity is accompanied by a multitude of perspectives, as the reports and narratives do not always agree. There are gaps and contradictions that are neither closed nor resolved in the book. Instead, they create a deliberately fragile picture that is much closer to the reality of the ambivalent main character's life than a straightforward narrative. Even the narrator in the novel does not know whom to trust more: the Stasi files or Uta's stories. He asks himself: “What if much of what she says is refuted?” The request to inspect the files at the Stasi archives shows that Uta is “both perpetrator and victim,” because as a perpetrator she is not granted access to a large part of her files. “You were allowed to find out much more about me than I was,” she complains to the narrator.Böckmann won the Jürgen Ponto Foundation Literature Prize in 2024 with his multi-layered debut novel, which is definitely worth reading. The jury rightly describes it as “one of the most exciting books of the year,” saying that this “porous biopic of an untold story” can “compete with the milestones of documentary literature.”

Clemens Böckmann: Was du kriegen kannst. Roman

München: Hanser, 2024. 416 S.

ISBN: 978-3-446-28121-9

You can find this title in our eLibrary Onleihe.

August 2025