“Fish discovers water last”: Designer Tomo Kihara in interview

Japanese designer and developer Tomo Kihara loves engaging with complex social problems and helping people think of alternatives. He says artificial intelligence has taught him many lessons about understanding context, human bias and opening up unexpected directions for idea generation, especially to benefit society.

What would you think if you were about to throw away an empty coffee cup and the garbage bin spoke to you and said “Please recycle this cup?” It might sound far-fetched, but it’s not. The Japanese designer Tomo Kihara has developed ObjectResponder, a mobile phone application using artificial intelligence to prototype ideas that can be rapidly tested and iterated. The tool uses Google Cloud Vision enabling designers to assign chat bot-like responses to objects recognized by the smartphone camera.

Kihara, who is based in Amsterdam, enjoys working with camera recognition-based interactions and predicts these are going to become ubiquitous in the next five to ten years. “Right now, if you look at the current urban spaces, there are already sensors that detect your body. So, for instance, if you go through automatic doors, there are infrared sensors that detect a person’s approach. And we don't really question doors opening automatically anymore. In the next few years, these simple sensors will be replaced by cameras enhanced with AI and it will be able to detect who you are and what you are doing - which is both scary and exciting at the same time.”

Kihara recalls from his experiment of setting up talking garbage bins in The Netherlands, that “there was a playful tension between man and machine and people didn't really like being told what to do by a computer.” Had he done this experiment back home in Tokyo, the 26-year-old designer believes the reaction would have been very different.

“In Japan, we are quite used to things talking to us,” he says. “Toilets talk to us a lot, we're quite used to that. Our toilets, our vending machines, our bathtubs talk to us, when the water temperature is getting too cold, or if we forgot to get the change, these machines will always say something. So, we're quite used to things talking back and deciding things for themselves.”

When it comes to artificial intelligence, Kihara observes a stark difference between Europe and East Asia. “When you talk about AI in Europe, the first thing anybody would say is about ethics and implications of that technology. It has this negative image surrounding it. While if you talk to people from East Asia, it's really all about the opportunities that the technology can create.”

He adds that this cultural difference in the approach of AI and technology might also partly lie in the animistic worldview based on the Shinto religion that is predominant in Japan, and the belief that all things, even inanimate things have spirits and wills of their own. And there’s also “an East Asian way of thinking that technology will save us all, that technology will make life better. While in Europe people are much more sceptical.” Kihara won't say which is good or bad, but says “it's always interesting to get these very different perspectives.”

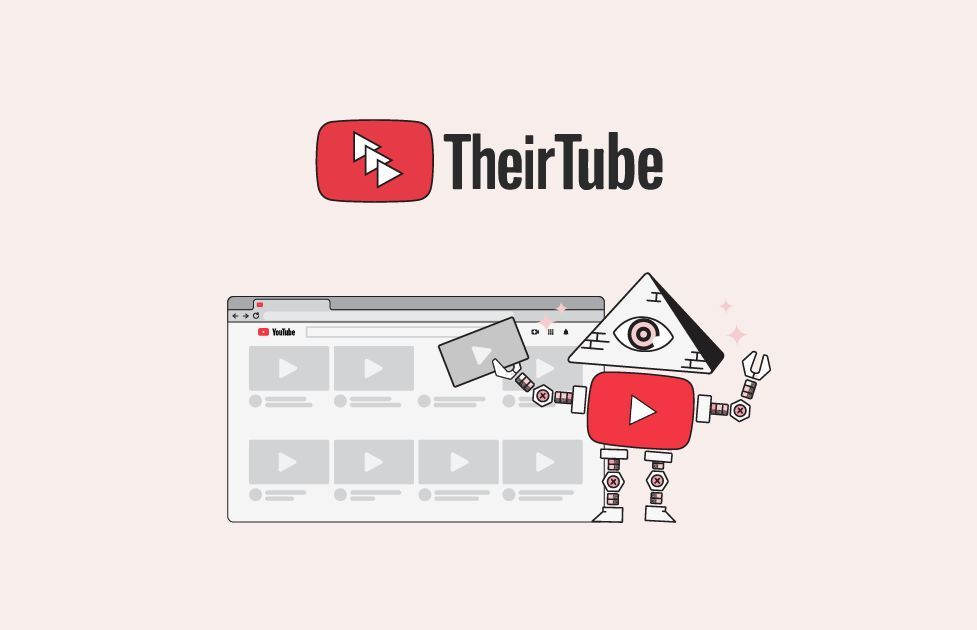

Tomo Kihara's "TheirTube" project turned heads across the online world

| © Tomo Kihara

Tomo Kihara's "TheirTube" project turned heads across the online world

| © Tomo Kihara

Tomo Kihara started his studies in the media design program at Keio University in Tokyo, but soon realised he wanted to focus more on social-design oriented projects: “I realised that The Netherlands was one of the best places to learn that.” Kihara moved to Europe to do his Master’s degree at the Delft University of Technology.

Soon, he was introduced to research of design and machine learning, and he was hooked. “I really thought it was fascinating because you are designing something that's out of your own control and there's a lot of uncertainty that could happen from what you design.”

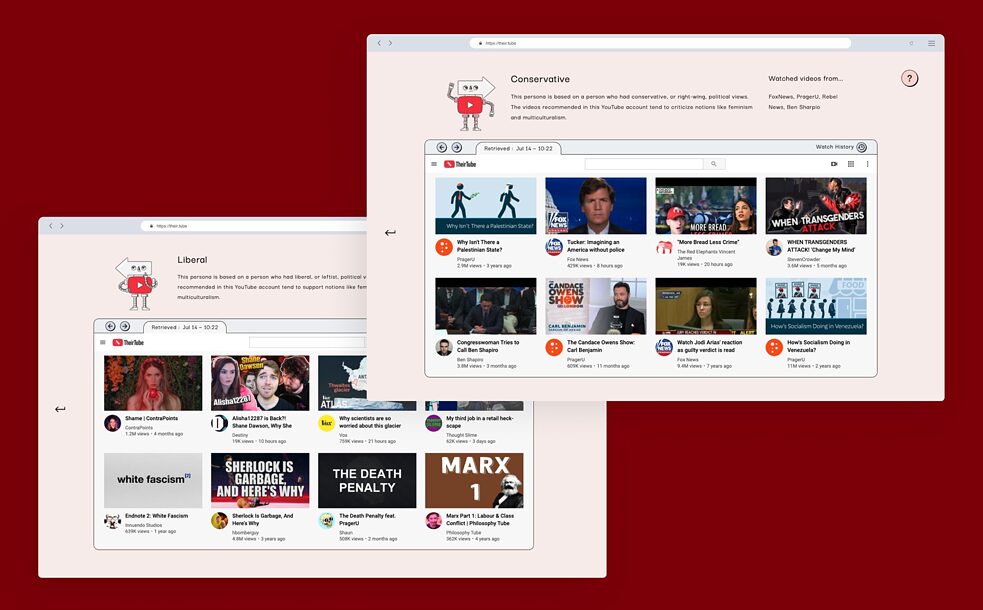

That fascination with the autonomous, decision-making aspect of AI inspired Kihara to create TheirTube – a project that allows users to step into someone else’s YouTube filter bubble and watch the videos that show up on their starting page.

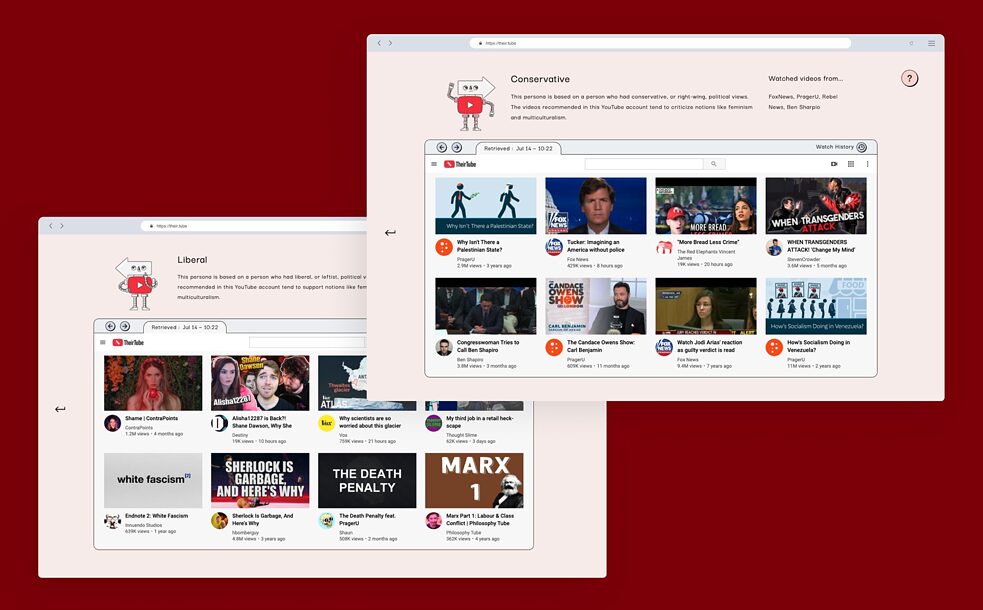

YouTube videos selected by TheirTube vary depending on the type of account setting used

| © Tomo Kihara

The project went viral on Reddit and social media and received a Mozilla Creative Media Award. TheirTube offers six personas users can choose from: fruitarian, prepper, liberal, conservative, conspiracist and climate denier and then shows what videos different political demographics get recommended by the world’s most popular video-sharing platform.

YouTube videos selected by TheirTube vary depending on the type of account setting used

| © Tomo Kihara

The project went viral on Reddit and social media and received a Mozilla Creative Media Award. TheirTube offers six personas users can choose from: fruitarian, prepper, liberal, conservative, conspiracist and climate denier and then shows what videos different political demographics get recommended by the world’s most popular video-sharing platform.

“In the past year there’s been a lot of super extreme content recommended by AI on YouTube and Facebook” says Tomo Kihara “Videos from QAnon claiming that COVID-19 was caused by 5G were frequently recommended.”

In the last months of 2020 Kihara says he has observed a crackdown on all conspiracy-related content and extremist videos, but he still hopes TheirTube will make people realize how biased their feeds are and how recommendation algorithms promote extremist ideologies and conspiracy theories. Kihara likes to use the proverb ‘fish discover water last’, which describes the current situation that “you don't really realise how biased your own feed is until you look at other people's feeds.”

Kihara has recently created another game uncovering bias in algorithms. As he was pondering about machines recognising cups and humans, he thought “what if it can start deciding subjective notions such as violence or sexiness or what is beautiful?” He was intrigued by one of Google’s open APIs which can be used to detect violent content and pornography.

“It’s quite fascinating that a machine gets to decide such a highly sensitive topic on its own, and it's being used behind Google's SafeSearch filter, which filters what we see of the Internet”.

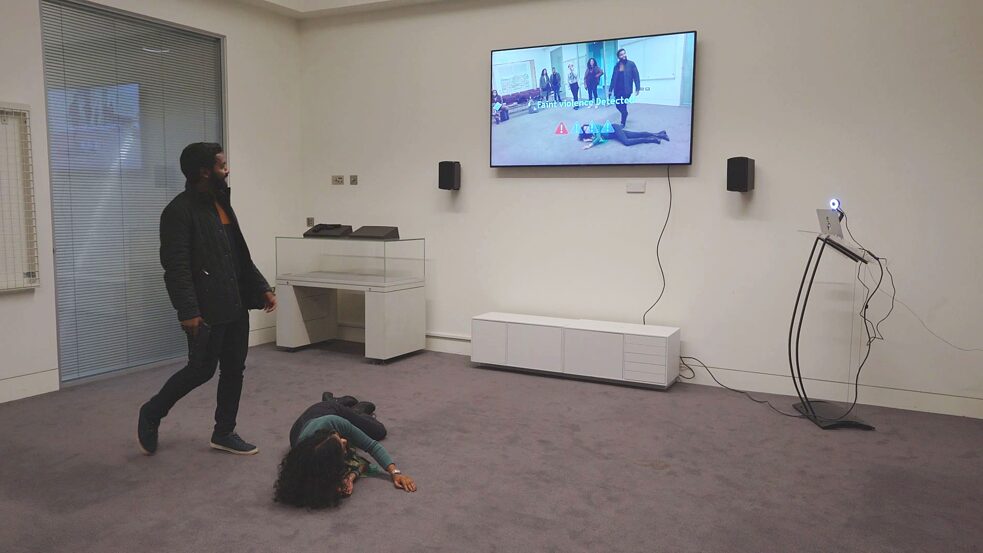

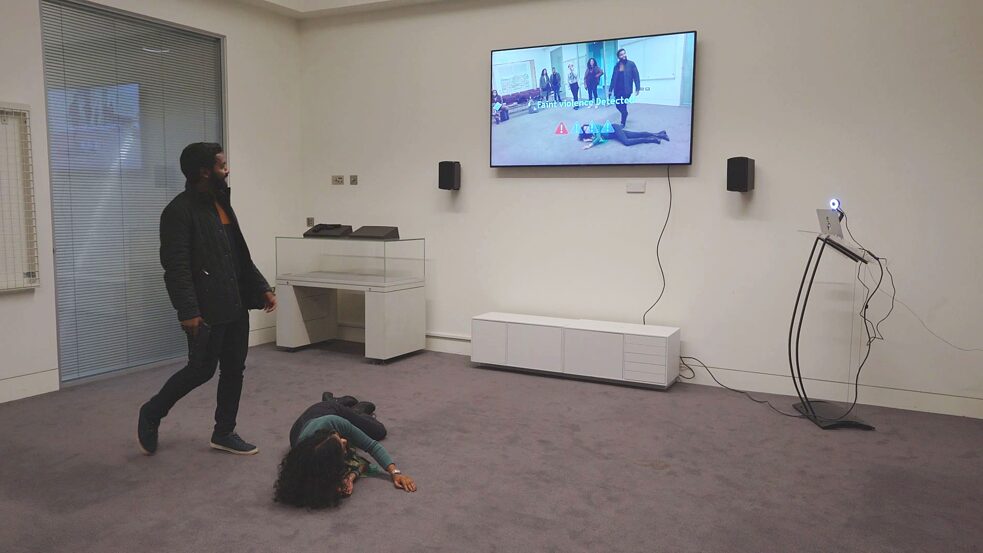

The game Kihara developed is called Is This Violence? It lets players experiment in real time on what the machine detects as violence as they engage in violence in the game. The results are confronting: There was a tendency for the violence score to increase when a darker-skinned person was acting out the violence. The score changed when the skin colour of the same photo is changed from light to dark too.

Kihara says the examples of this bias are numerous: the German NGO AlgorithmWatch showed earlier this year how Google Vision Cloud labelled an image of a dark-skinned individual holding a thermometer as a “gun,” while a similar image with a light-skinned individual was labelled “electronic device.” This prompted Google to act, but points to a much wider problem.

For Kihara there is no such thing as an unbiased human and the same applies to machines that we make. But he says the aim of his projects is not to criticize big tech companies or the technology itself, “the aim is to come up with a way to find these unwanted biases in the system through play.” Participants take part in a staged "Is this violence?" session from Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

Participants take part in a staged "Is this violence?" session from Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

The concept of play is a constant thread throughout all of Tomo Kihara’s works. “Play can also be about exploring an alternative approach to a systematic problem in a safe manner” he says. “I really like the approach of not really trying to find a solutionist way, but rather allowing people to become creative and try to look at a problem from a different angle.”

Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

The young designer says his practice has been influenced by Dutch Historian, Johan Huizinga, and his 1938 book, Homo Ludens, which outlines the concept of play in the generation of culture. He’s especially interested in the interpretation of Huizinga’s ideas around “magic circles” that create safe experimental spaces for creative problem-solving.

“When people play, they are in this metaphorical space of magic circles where the rules of the real world are not applied. People fighting in the streets are a problem, but in a boxing ring it’s different, it has a set of rules,” Kihara explains. “And what I really like about that is that it becomes a safe space to experiment. You can do it in a safe and constructive manner if it's in this magic circle.”

“Imagine something like a design workshop, it allows people to be braver because it's within this magic circle of a workshop. People can make scrappy things and it doesn't matter. And that attitude itself is super important to create new things.”

Learn more about Tomo Kihara's views on the future of creative AI here.

Kihara, who is based in Amsterdam, enjoys working with camera recognition-based interactions and predicts these are going to become ubiquitous in the next five to ten years. “Right now, if you look at the current urban spaces, there are already sensors that detect your body. So, for instance, if you go through automatic doors, there are infrared sensors that detect a person’s approach. And we don't really question doors opening automatically anymore. In the next few years, these simple sensors will be replaced by cameras enhanced with AI and it will be able to detect who you are and what you are doing - which is both scary and exciting at the same time.”

Talking toilets

Kihara recalls from his experiment of setting up talking garbage bins in The Netherlands, that “there was a playful tension between man and machine and people didn't really like being told what to do by a computer.” Had he done this experiment back home in Tokyo, the 26-year-old designer believes the reaction would have been very different.

“In Japan, we are quite used to things talking to us,” he says. “Toilets talk to us a lot, we're quite used to that. Our toilets, our vending machines, our bathtubs talk to us, when the water temperature is getting too cold, or if we forgot to get the change, these machines will always say something. So, we're quite used to things talking back and deciding things for themselves.”

When it comes to artificial intelligence, Kihara observes a stark difference between Europe and East Asia. “When you talk about AI in Europe, the first thing anybody would say is about ethics and implications of that technology. It has this negative image surrounding it. While if you talk to people from East Asia, it's really all about the opportunities that the technology can create.”

He adds that this cultural difference in the approach of AI and technology might also partly lie in the animistic worldview based on the Shinto religion that is predominant in Japan, and the belief that all things, even inanimate things have spirits and wills of their own. And there’s also “an East Asian way of thinking that technology will save us all, that technology will make life better. While in Europe people are much more sceptical.” Kihara won't say which is good or bad, but says “it's always interesting to get these very different perspectives.”

Tomo Kihara's "TheirTube" project turned heads across the online world

| © Tomo Kihara

Tomo Kihara's "TheirTube" project turned heads across the online world

| © Tomo Kihara

Stepping inside a bubble

Tomo Kihara started his studies in the media design program at Keio University in Tokyo, but soon realised he wanted to focus more on social-design oriented projects: “I realised that The Netherlands was one of the best places to learn that.” Kihara moved to Europe to do his Master’s degree at the Delft University of Technology.

Soon, he was introduced to research of design and machine learning, and he was hooked. “I really thought it was fascinating because you are designing something that's out of your own control and there's a lot of uncertainty that could happen from what you design.”

That fascination with the autonomous, decision-making aspect of AI inspired Kihara to create TheirTube – a project that allows users to step into someone else’s YouTube filter bubble and watch the videos that show up on their starting page.

YouTube videos selected by TheirTube vary depending on the type of account setting used

| © Tomo Kihara

The project went viral on Reddit and social media and received a Mozilla Creative Media Award. TheirTube offers six personas users can choose from: fruitarian, prepper, liberal, conservative, conspiracist and climate denier and then shows what videos different political demographics get recommended by the world’s most popular video-sharing platform.

YouTube videos selected by TheirTube vary depending on the type of account setting used

| © Tomo Kihara

The project went viral on Reddit and social media and received a Mozilla Creative Media Award. TheirTube offers six personas users can choose from: fruitarian, prepper, liberal, conservative, conspiracist and climate denier and then shows what videos different political demographics get recommended by the world’s most popular video-sharing platform.“In the past year there’s been a lot of super extreme content recommended by AI on YouTube and Facebook” says Tomo Kihara “Videos from QAnon claiming that COVID-19 was caused by 5G were frequently recommended.”

In the last months of 2020 Kihara says he has observed a crackdown on all conspiracy-related content and extremist videos, but he still hopes TheirTube will make people realize how biased their feeds are and how recommendation algorithms promote extremist ideologies and conspiracy theories. Kihara likes to use the proverb ‘fish discover water last’, which describes the current situation that “you don't really realise how biased your own feed is until you look at other people's feeds.”

Is this violence?

Kihara has recently created another game uncovering bias in algorithms. As he was pondering about machines recognising cups and humans, he thought “what if it can start deciding subjective notions such as violence or sexiness or what is beautiful?” He was intrigued by one of Google’s open APIs which can be used to detect violent content and pornography.

“It’s quite fascinating that a machine gets to decide such a highly sensitive topic on its own, and it's being used behind Google's SafeSearch filter, which filters what we see of the Internet”.

The game Kihara developed is called Is This Violence? It lets players experiment in real time on what the machine detects as violence as they engage in violence in the game. The results are confronting: There was a tendency for the violence score to increase when a darker-skinned person was acting out the violence. The score changed when the skin colour of the same photo is changed from light to dark too.

Kihara says the examples of this bias are numerous: the German NGO AlgorithmWatch showed earlier this year how Google Vision Cloud labelled an image of a dark-skinned individual holding a thermometer as a “gun,” while a similar image with a light-skinned individual was labelled “electronic device.” This prompted Google to act, but points to a much wider problem.

For Kihara there is no such thing as an unbiased human and the same applies to machines that we make. But he says the aim of his projects is not to criticize big tech companies or the technology itself, “the aim is to come up with a way to find these unwanted biases in the system through play.”

Participants take part in a staged "Is this violence?" session from Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

Participants take part in a staged "Is this violence?" session from Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

Playful interventions

The concept of play is a constant thread throughout all of Tomo Kihara’s works. “Play can also be about exploring an alternative approach to a systematic problem in a safe manner” he says. “I really like the approach of not really trying to find a solutionist way, but rather allowing people to become creative and try to look at a problem from a different angle.”

Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

Tomo Kihara

| © Tomo Kihara

The young designer says his practice has been influenced by Dutch Historian, Johan Huizinga, and his 1938 book, Homo Ludens, which outlines the concept of play in the generation of culture. He’s especially interested in the interpretation of Huizinga’s ideas around “magic circles” that create safe experimental spaces for creative problem-solving.

“When people play, they are in this metaphorical space of magic circles where the rules of the real world are not applied. People fighting in the streets are a problem, but in a boxing ring it’s different, it has a set of rules,” Kihara explains. “And what I really like about that is that it becomes a safe space to experiment. You can do it in a safe and constructive manner if it's in this magic circle.”

“Imagine something like a design workshop, it allows people to be braver because it's within this magic circle of a workshop. People can make scrappy things and it doesn't matter. And that attitude itself is super important to create new things.”

Learn more about Tomo Kihara's views on the future of creative AI here.