Amrita Hepi and Sam Lieblich talk about their new chatbot ‘Neighbour’

As we start to talk more to Google or Siri than to our neighbours, what does this do to the human mind? Choreographer Amrita Hepi and neuroscientist Sam Lieblich spoke to Goethe-Institut about their new digital art chatbot Neighbour.

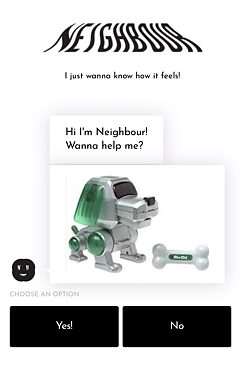

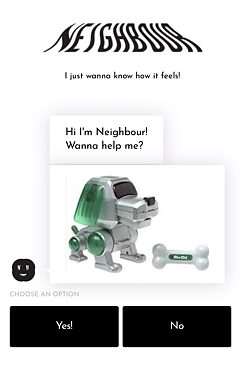

Posing as the virtual assistant of the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art (ACCA), Neighbour is a playful algorithmic chatbot who wants to know what “it” is and what “it” feels like, in an attempt to locate the enigmatic secret to life that defines us all as humans.

For choreographer Amrita Hepi and neuroscientist Sam Lieblich, a shared love for experimental performance and the enigma of language and subjectivity brought them together to work on the bot and explore the question “How does it feel?”

The artists hope Neighbour will challenge people, in a fun and entertaining way, who sometimes say things that they think are natural and seamless, but in fact they don’t really understand themselves. “On an everyday basis, we use so many ways to describe how we feel without ever locating the body in it,” says Hepi.

While developing the chatbot, Lieblich drew on his work in psychiatry and the nuanced linguistic interaction of the psychiatric interview, while Hepi contributed her experience as a dancer and choreographer. The artistic process was as much about movement, as it was a deep conversation.

“How can we get people to talk about a body in a room, a body in relation to the things around them? How can we draw this question out so people can actually reflect on it?” Hepi says. The two artists posed for many of the images and memes that Neighbour likes to use

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

The chatbot Neighbour has been trained using pop songs, snippets from history, philosophy, flirting techniques, favourite passages from books and 100,000 tweets starting with the words ‘how does it feel?’

The two artists posed for many of the images and memes that Neighbour likes to use

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

The chatbot Neighbour has been trained using pop songs, snippets from history, philosophy, flirting techniques, favourite passages from books and 100,000 tweets starting with the words ‘how does it feel?’

“And still the bot really really struggles,” says Lieblich. “It just goes to prove that the main thing that a human does when it uses language is not words. We do a different thing when we are communicating that has an association with words but is not quite speakable.”

“It's what Jacques Lacan meant when he said ‘that there is no such thing as a Metalanguage.’ There's something meta going on, but it can't be said in language. Whereas everything the bot does is in language.”

For Hepi, Neighbour as a digital artwork probes what she sees as the ridiculousness of language and a shared idea of subjectivity, both online and offline. Hepi argues that subjectivity is about “using what we can to try and touch on what could be a shared, or varied, experience. And to be able to articulate this in any way possible and, in trying to, we are sharing a hyper-subjectivity.”

The interactive artwork Neighbour aims to expose the hyper-subjectivity into which every human being is now inserted through their participation in technocapitalism, fuelled by algorithms. It also challenges us to consider whether AI is just another technology humans are evolving with, like the wheel or the internal combustion engine.

“I think it makes you ponder: is the machine training us? Are we training it?,” Hepi asks.

In comparison to how humans have used language and transmitted ideas over the centuries, in forms like poems and novels, it’s arguable whether we should classify what algorithms and AI produce as cultural products. Psychiatrist Lieblich says he’s still not sure — and provides both arguments in favour and against. Neighbour the chatbot

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

Neighbour the chatbot

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

“One difference is that AI changes as it interacts with us,” he says. “But then, that's the same for novel writing. The form of the novel changed over time. People look a certain way and even have surgical procedures of a certain kind because they're better suited to gaming the algorithm in various social media products. That's something that's different. But then fashion influenced the novel and the novel influenced the fashion, and that always been that way.”

Another thing that is certainly different is the incredible pace at which algorithms present us with new information. What impact does this speed and the accompanying information overload have on our human mind?

Here too, Sam Lieblich looks for perspective. “There have always been complaints about information overload, starting with notable writers in classical Greece. I think that might be a universal human experience of culture. I'm not sure that it's the form of the algorithm that overloads us so much, as it is just a quality of culture.”

What has changed is the subjectivity, says Lieblich. In epic poetry for instance, the subject acts within history, performs a heroic feat or lives through a tragedy. Lieblich argues that the novel is about “interiority”, changing the narrative perspective focusing less on telling and more on showing. Today the dominant genre is the news feed or the timeline, where people think about themselves, images dominate, and there’s no unfolding over time.

“People have this experience where they're scrolling down the feed and you see there's been an explosion in Lebanon and then you see the butt cheeks of a friend of yours, and then you see that somebody had a baby and then somebody else had a coffee. And in the space of three seconds, you've gone from tragedy to titillation to farts.”

The increasing speed, the lack of thematic connection and also dependency on mobile devices have clear, harmful effects. But the biggest harm that Lieblich sees with the patients coming into his practice is not mobile phone addiction, but rather the intrusion of capitalist imperatives into our homes.

“They are feeling oppressed by the high pace of turnover, the casualisation of labour. And that's an Internet phenomenon, the atomisation of people into uberised wealth producing entities.”

Neighbour wants to know about personhood in the age of the algorithm, say the artists

Neighbour wants to know about personhood in the age of the algorithm, say the artists

Lieblich says the Uber driver working at all hours is the archetypal turbo-capitalist model. “They're scarcely available to be a family member and a faceless algorithm tells them where to go in the real world. The amount of money they make is dynamically determined by an algorithm.”

It's very impersonal, he adds, and very efficient at producing convenience for the people who use Uber, as well as profits for the company. “So the more we get involved with the algorithm, if things stay the same, the more efficiently we are all exploited.”

While Hepi has previously worked with bots in her art and dance practice, it was the first time for Lieblich. Working with AI, he came to the realisation that “AI is not that scary, it's pretty dumb, except for certain narrow cases. So any fears that we’ll be overtaken as a species by an intellect that's greater than us, I don't think it's a worry.”

But what he does worry about is “that we live to the dictates of the algorithms, fail to produce our own novelty and instead get caught in repetitive loops produced by the algorithm.”

And that’s what both artists hope users of Neighbour will take away: an awareness of the ways that AI is training us, so that our interaction with AI and algorithms in the future is of the conscious kind.

“We’re always training each other,” Lieblich says. “And we have to stay active. Otherwise, if I'm passive, I become one more variable inside the algorithm.”

Neighbour has been commissioned by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art for the ACCA Open, a series of six contemporary art projects in the digital realm to continue to work with and support contemporary artists during gallery closures caused by COVID-19.

Amrita Hepi and Sam Lieblich share thoughts about the future of creative AI on their network profiles.

For choreographer Amrita Hepi and neuroscientist Sam Lieblich, a shared love for experimental performance and the enigma of language and subjectivity brought them together to work on the bot and explore the question “How does it feel?”

The artists hope Neighbour will challenge people, in a fun and entertaining way, who sometimes say things that they think are natural and seamless, but in fact they don’t really understand themselves. “On an everyday basis, we use so many ways to describe how we feel without ever locating the body in it,” says Hepi.

While developing the chatbot, Lieblich drew on his work in psychiatry and the nuanced linguistic interaction of the psychiatric interview, while Hepi contributed her experience as a dancer and choreographer. The artistic process was as much about movement, as it was a deep conversation.

“How can we get people to talk about a body in a room, a body in relation to the things around them? How can we draw this question out so people can actually reflect on it?” Hepi says.

The two artists posed for many of the images and memes that Neighbour likes to use

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

The chatbot Neighbour has been trained using pop songs, snippets from history, philosophy, flirting techniques, favourite passages from books and 100,000 tweets starting with the words ‘how does it feel?’

The two artists posed for many of the images and memes that Neighbour likes to use

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

The chatbot Neighbour has been trained using pop songs, snippets from history, philosophy, flirting techniques, favourite passages from books and 100,000 tweets starting with the words ‘how does it feel?’“And still the bot really really struggles,” says Lieblich. “It just goes to prove that the main thing that a human does when it uses language is not words. We do a different thing when we are communicating that has an association with words but is not quite speakable.”

“It's what Jacques Lacan meant when he said ‘that there is no such thing as a Metalanguage.’ There's something meta going on, but it can't be said in language. Whereas everything the bot does is in language.”

Hyper-subjectivity of technocapitalism

For Hepi, Neighbour as a digital artwork probes what she sees as the ridiculousness of language and a shared idea of subjectivity, both online and offline. Hepi argues that subjectivity is about “using what we can to try and touch on what could be a shared, or varied, experience. And to be able to articulate this in any way possible and, in trying to, we are sharing a hyper-subjectivity.”

The interactive artwork Neighbour aims to expose the hyper-subjectivity into which every human being is now inserted through their participation in technocapitalism, fuelled by algorithms. It also challenges us to consider whether AI is just another technology humans are evolving with, like the wheel or the internal combustion engine.

“I think it makes you ponder: is the machine training us? Are we training it?,” Hepi asks.

In comparison to how humans have used language and transmitted ideas over the centuries, in forms like poems and novels, it’s arguable whether we should classify what algorithms and AI produce as cultural products. Psychiatrist Lieblich says he’s still not sure — and provides both arguments in favour and against.

Neighbour the chatbot

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

Neighbour the chatbot

| © Amrita Hepi / Sam Lieblich

“One difference is that AI changes as it interacts with us,” he says. “But then, that's the same for novel writing. The form of the novel changed over time. People look a certain way and even have surgical procedures of a certain kind because they're better suited to gaming the algorithm in various social media products. That's something that's different. But then fashion influenced the novel and the novel influenced the fashion, and that always been that way.”

Another thing that is certainly different is the incredible pace at which algorithms present us with new information. What impact does this speed and the accompanying information overload have on our human mind?

Here too, Sam Lieblich looks for perspective. “There have always been complaints about information overload, starting with notable writers in classical Greece. I think that might be a universal human experience of culture. I'm not sure that it's the form of the algorithm that overloads us so much, as it is just a quality of culture.”

“From tragedy to titillation to farts”

What has changed is the subjectivity, says Lieblich. In epic poetry for instance, the subject acts within history, performs a heroic feat or lives through a tragedy. Lieblich argues that the novel is about “interiority”, changing the narrative perspective focusing less on telling and more on showing. Today the dominant genre is the news feed or the timeline, where people think about themselves, images dominate, and there’s no unfolding over time.

“People have this experience where they're scrolling down the feed and you see there's been an explosion in Lebanon and then you see the butt cheeks of a friend of yours, and then you see that somebody had a baby and then somebody else had a coffee. And in the space of three seconds, you've gone from tragedy to titillation to farts.”

The increasing speed, the lack of thematic connection and also dependency on mobile devices have clear, harmful effects. But the biggest harm that Lieblich sees with the patients coming into his practice is not mobile phone addiction, but rather the intrusion of capitalist imperatives into our homes.

“They are feeling oppressed by the high pace of turnover, the casualisation of labour. And that's an Internet phenomenon, the atomisation of people into uberised wealth producing entities.”

Lieblich says the Uber driver working at all hours is the archetypal turbo-capitalist model. “They're scarcely available to be a family member and a faceless algorithm tells them where to go in the real world. The amount of money they make is dynamically determined by an algorithm.”

It's very impersonal, he adds, and very efficient at producing convenience for the people who use Uber, as well as profits for the company. “So the more we get involved with the algorithm, if things stay the same, the more efficiently we are all exploited.”

Is AI dumb and making us dumber?

While Hepi has previously worked with bots in her art and dance practice, it was the first time for Lieblich. Working with AI, he came to the realisation that “AI is not that scary, it's pretty dumb, except for certain narrow cases. So any fears that we’ll be overtaken as a species by an intellect that's greater than us, I don't think it's a worry.”

But what he does worry about is “that we live to the dictates of the algorithms, fail to produce our own novelty and instead get caught in repetitive loops produced by the algorithm.”

And that’s what both artists hope users of Neighbour will take away: an awareness of the ways that AI is training us, so that our interaction with AI and algorithms in the future is of the conscious kind.

“We’re always training each other,” Lieblich says. “And we have to stay active. Otherwise, if I'm passive, I become one more variable inside the algorithm.”

Neighbour has been commissioned by the Australian Centre for Contemporary Art for the ACCA Open, a series of six contemporary art projects in the digital realm to continue to work with and support contemporary artists during gallery closures caused by COVID-19.

Amrita Hepi and Sam Lieblich share thoughts about the future of creative AI on their network profiles.