Sonic Resistance in Myanmar

Anthems of Social Change

By Pinky Htut Aung, 2021The sound of resistance is the resistance to normalcy. It is an abrupt refusal to function as the military government dictates. In Myanmar, when we mention the sound of resistance, I can’t think of a more iconic sound than »Doh A Yay« (which translates as »our rights«) accompanied by an image of a group of people with their fists up in the air, clenched tight. The same interplay of sound+image was seen in the protests of 1974, 1988, 2007, and now again in 2021.

The sound of resistance is the resistance to normalcy. It is an abrupt refusal to function as the military government dictates. In Myanmar, when we mention the sound of resistance, I can’t think of a more iconic sound than »Doh A Yay« (which translates as »our rights«) accompanied by an image of a group of people with their fists up in the air, clenched tight. The same interplay of sound+image was seen in the protests of 1974, 1988, 2007, and now again in 2021.

In the early hours of the 1st of February, we woke up to find our voices and rights as citizens taken over under the pretext of a »State of Emergency«. Newly elected members of parliament were supposed to have gathered in parliament, but they had been detained in the capital, Nay Pyi Taw. Phone lines were cut, and we were shut off from the world. History was repeating itself.

Most of the older generation has experienced something similar and has a (resigned) idea of how things will unfold, but for the younger generation, this was an unacceptable violation of human rights on many levels, especially living in 2021.

We were told to stay peaceful for 72 hours because some believed that the military was waiting for a riot to legitimize their coup. Others believed it was important to show defiance within these first 72 hours, to show the international community that the general public was discontent with the coup. During those early hours, we felt a sense of loss, were terrified by uncertainty, and filled with rage. We focused on spreading awareness through social media and seeking help from international figures whilst maintaining peace on the streets.

Already in the first days we witnessed a few political detainees including civilian government members, writers, musicians, filmmakers, student leaders, and poets. Some celebrities who had strong ties with the National League of Democracy political party (NLD, the democratically-elected governing party that was overthrown by the military coup) went into hiding.

On the third day of the coup the whole city showed solidarity against the military using various methods of nonviolent rebellion; banging pots and pans, honking car horns, and civil servants refusing to go to work. The early resistance movement was initiated by doctors in Mandalay, who refused to go to work and started the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) which was later joined by engineers, teachers, and lawyers. The movement gained broad public backing. The majority of us started changing our Facebook profile pictures to show support for our rightful government and to support the CDM.

Musicians’ Protest in February: Endorsing CDM. The words on the poster in the first picture say, »Our Music,« while the word on the ground in the second picture says, »Our Music.« Photos by Soe Thiha.

The nightly pot banging was followed by playing the song »Kabar Ma Kyay Buu« (»Until the End of the World«) which is a pro-democracy song adapted from US progressive rock band Kansas’s 1997 classic »Dust in the wind«. »Kabar Ma Kyay Buu« was originally written during the (19)88 uprising by Naing Myanmar and has been the emblem of hope and democracy in Myanmar ever since. The song came back even stronger this time around, as it was sung and played through speakers every night. Some people would sing along with grievance-filled tears and a determination to fight for those who had sacrificed their lives for democracy since the 88 uprising. Naing Myanmar wrote seven revolutionary songs during the late 1980s, but »Kabar Ma kyay Buu« remains the most well-known of them all. It encourages protesters to be fearless and to not surrender.

After the 8pm - 4am curfew had been announced on the ninth day, people continued hitting their metal wares from inside their homes. Some would even climb up to the rooftops to slam the metal, as if they were declaring their resentment to the whole world.

Our nights have never been peaceful since the coup, as the military would abduct people at nighttime. We even believe that they set the 8pm curfew purposely, so that they can sneak around easily and raid houses. Whenever they came to take away the people for »questioning« the whole neighbourhood would show solidarity by banging pots and pans and intervening in the arrest. The sound of pots and pans after the curfew became a means of alerting residents in the area that intruders are coming.

Ever since the military started to release prisoners, mainly ex-convicts, most of the time drugged and armed to disrupt neighbourhoods by poisoning the water or perpetrating arson attacks on houses, our nights have become even longer. People took turns on neighborhood watch and many townships were filled with banging pots signaling nightly intruders. It was truly nightmarish hearing all the commotion from both near and far.

We know that the pot banging movement was affecting the military when they started patrolling the streets, threatening to shoot anyone who made noise. We saw a decrease in the numbers of households who hit pots and pans due to the presence of military soldiers in neighbourhoods. Some would switch off their lights and still hit them from their rooms, continuing to show solidarity, while making it harder for the military to pinpoint where the noises came from.

The pot-banging sessions have proven to be extremely effective in many ways. Having been drained with anxiety, devastation and panics from protesting outside under the sun the whole day or from absorbing the news from Social Media all day, I think the pot banging session was the most anticipated activity during the day. That was when we felt the release of letting out our emotions, and channeling it by vigorously hitting the metals. Noise in Yangon, an experimental noise community, also started playing live from their Facebook page to accompany the 8pm noise making sessions. One can wonder how the military government would feel every night around this time as the whole nation made noises to tell them that they were unwanted, and that people wanted an end to their regime.

One powerful song that accompanied the early marches was called »Thway Thitsar« (»Blood Oath«) written by the well-respected singer-songwriter Htoo Eain Thin. He had written the song while in hiding after the 88 uprising. The vocal part was recorded later in 1991 by singer Moon Aung in Bangkok. The song has been used for anti-military rule and pro-democracy marches and activities ever since.

The influence of this marching song is phenomenal. People don’t seem to get bored of it and the lyrics and melody get stuck in your mind, the beat of the song sends your heart racing and your blood boiling. It united the people. The song is often looped and performed repeatedly, further increasing its energy and bringing people together.

Whether small groups marched the streets or large groups protested at major gathering points, music was an essential component played in between protest chants. We knew this would be a long battle and it was not easy to protest all day under the scorching sun. Protesters need some kind of entertainment; some songs to keep them motivated, focused, and to elicit a sense of belonging. A song such as »Khun Arr Phyae Meenge« (»Don’t give up little one«) by another respected singer-songwriter, Khin Maung Toe, is very comforting to sing and hear, and tells us to be resilient. While the people were protesting, there were always those that provided generous support by means of food and beverages, and showed solidarity.

A few days into the early non-violent protests, we discovered that some had brought their snare drums to accompany the chants, which sounded especially great when the protesters sang the »Thway Thitsar« song. The sound of the snares empowered each protest chant, accompanying our demands and the ultimate wish to end military rule. Having a rhythm always kept things flowing.

To get international media attention and to keep the protests fresh, those of the young generation came up with innovative protest tactics; creating different themes, trolling the police, dressing up into eye-catching outfits, creating very bold protest signs which went from displaying deep messages to rather funny ones.

Since music and performance acts were also methods of peaceful protest, artists and musicians began providing live performances to energize the crowds. Celebrities would hold megaphones and lead chants, using their influence to attract larger crowds and to keep people motivated. This in turn put them at risk of being put on the arrest warrant list, since the Military targeted the protest leaders.

There were also many street performances around major gathering points; rappers were freestyling and protesters came out from the crowds to join them, dancers were performing, poets were reciting their emotions and discontent, performance artists were expressing their feelings towards this injustice through their bodies, and musicians were amplifying the protest chants and revolutionary songs with their instruments.

As the Civil Disobedience Movement escalated, we knew that it was a really effective tactic to cripple the Military government, in addition to boycotting their businesses. Some protesters came up with different ways to cause traffic to prevent non-CDM civil servants from going to work, while others tried to persuade them to stop going to work.

As the demonstrations against military rule got creative with humorous acts, some of the public began to fear that the protests would start to look like a festival, that they would lose focus and stray from their original goals. Others believed that creativity and a sense of humor was a great way to get international attention. They also believed that it was important to add an element of fun in these movements because it was a long battle and without any entertainment, people’s motivation would die off easily. The conflict between those two mindsets continued for a while but one thing was certain: people still decided to be out on the street despite the rumours and warnings of violent crackdowns from the police. They all had already taken a risk of being targeted.

Because of warnings of police crackdowns, most music performers keep their set-lists short, and move around between different major gathering points to perform. There was one interesting revolution song, written with an orchestral arrangement, that came out in early February, called »Revolution« by GenerationZ MM group. With its revolutionary words and bass drum, it sounds like battle music. That really set your mind to fight and served to prepare you well for what was coming. This was the type of song that makes your hair stand on end. What was more amazing was that, a week later after the song was published, the group decided to perform live in two major points in Yangon. It was a huge and risky challenge considering the size of the band; up to 30 instrumentalists and a choir of about 20 members. But they did so quite smoothly and briefly. Witnessing the performance for only 10 minutes gave us a lot of courage and strength, and brought some people to tears as they were reminded of the need to put an end to the injustices against us at any cost.

Later in February, a really upbeat song which has more positive energy in it came about and it is called »A lo Ma Shi«(»We don’t Need«) and it became widely used during protests. It has a sense of persistence in the melody and lyrics, and a rhythmic sound of clashing metal that was fun to clap along with, and which kept protesters entertained and high-spirited.

The Mizzima TV channel on Youtube would broadcast the revolutionary songs live, starting off with »A lo Ma Shi« at 8pm, which is perfect for those who protested with pots and pans indoors. I remember singing and dancing while hitting the metal plate rhythmically with the song.

Deadly crackdowns in Yangon took place a bit later than in other major cities, and as the death tolls increased and the crackdowns got more violent, we saw the street performances disappear, and large long gatherings split into smaller rallies along the streets. Instead of meeting at major gathering points, each township[1] hosted protests while putting up barricades in the streets to slow down the police, securing the neighbouring houses to cooperate and allow protesters to hide inside in case the police began chasing them. Those protests were again accompanied by the sound of snare drums. Songs such as »Thway Thitsar« and »Alo Ma Shi« were played in between chants while protesters would clap along to keep the flow going. Our goal is to make each protest powerful, and as safe as possible. There were also a few pop up performances in some neighbourhoods; very quick sets of just a few songs, often accompanied by poets expressing their rage, as well as someone scouting the perimeter or barricading the streets.

Many youth-led movements took on digital formats, not least because of safety concerns; coming face to face with the police during a crackdown is an unfair fight, since they have weapons and we only have makeshift tools to defend ourselves. After losing many lives to the military we have to come up with smarter ways to ensure our safety. An operation called Hanoi Hannah began, with the objective to blast audio files where soldiers can hear them, all the while retaining a safe distance to prioritize the safety of the person carrying out the task. Operation Hanoi Hannah believes that after some time, the minds of the soldiers will give in to the messages included in these intriguing audio clips, so that eventually the soldiers will join the Civil Disobedience Movement and the citizen’s fight for freedom. Each audio track consists of a script aimed to bend the minds of the soldiers – to shame them, to frighten them, to guilt trip them – narrated with agony by voice actors over daunting background music. These audio creations can definitely capture your attention from beginning to end. The operation’s name itself was inspired by Hanoi Hannah from the Vietnam War[1].

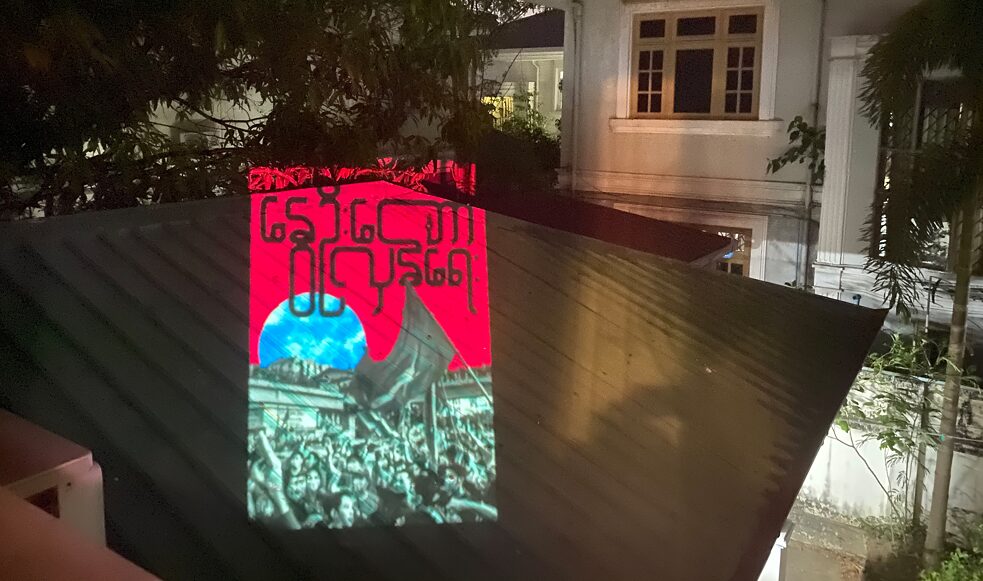

Another similar campaign is 100 projects, where people use projectors to display 10-minute videos compilations of artworks, illustrations, photographs, and video clips related to the revolution. The videos are screened indoors, and outdoors on buildings, landmarks, and public spaces. The nationwide campaign now also includes participants from other countries who are against Myanmar’s military rule.

Outdoor projections in support of CDM. Photo by Pinky Htut Aung.

Digital activism became another safer and effective movement that grew after witnessing the atrocities caused by the military; artists began streaming online live performances, and sharing new revolutionary songs or thought-provoking posters and illustrations.

One great example of digital activism is an initiative called Rap Against Junta, a creative resistance movement consisting of MCs, producers, DJs, sound engineers, event organizers, and graffiti artists. Most of the artists used their acronyms when releasing their songs, but there is one bold artist named Floke Rose who would release under his original artist name, despite already being on an arrest warrant list; an example of a fearless defiance. The initiative released a song named »Dictators must Die« by Floke Rose and Cori Rey from Myanmar, in collaboration with artists from Indonesia, India, Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong. This movement allows artists from across the globe to unite and help spread the message, which contributes a great deal to bringing about social change.

Thanks to netizens from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand and Myanmar, an online multinational movement to advocate democracy, called »Milk tea Alliance3,« was also born. It was originally an internet meme created in response to Chinese nationalist comentors on social media but had evolved into a »leaderless protest movement pushing for change across Southeast Asia.« On the 28th of February, Myanmar held a Milk Tea Alliance day strike and received solidarity support from the three founding regions Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand. The movement also gained support from South Korea, Philippines, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Belarus, and Iran.

Another gesture of showing resistance and solidarity is a three-finger salute, originated in the Hunger Games film which was first adopted by Thailand and now by Myanmar as well. Having a symbolism is also integral during a revolution as they are difficult to ban completely and just seeing someone raising a three finger salute gives you extra energy and returning the salute reinforced the solidarity and your defiance.

Being a noise musician myself, hearing my city making noise, hearing the dings and clashes of metal from the horizon, was the most satisfying and stimulating moment in the early days. Now, months into the coup, one can hardly hear these sounds due to the presence of informants and soldiers. The absence of that wave of noise is indeed a bit discouraging, and now more and more people are calling on everyone to unite again to rekindle this movement.

The sound of our protest is an absolute defiance, it is anything and everything to end the dictatorship. The sound of the asynchronous steps in a march, the rhythm of the chants, the beats, the metal noises, the symphony of horns from cars, the revolutionary songs, the voices, the frequencies, are all the sound of resistance. While some people may have lowered their voices, or while some may have fallen silent, there’s always a note that lingers. The sound of resistance can ignite the fire within us and can unite us.

[1] Cities in Myanmar are divided into townships, which further subdivide into districts and wards. Yangon is made up of 33 townships.

[2] Hanoi Hannah is the nickname given to a woman who became famous among US soldiers for her propaganda broadcasts on Radio Hanoi during the Vietnam War.

[3] Milk tea is a popular drink found in the founding three countries; Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand. The late members, Myanmar and India, also share variations of milk teas.

In the early hours of the 1st of February, we woke up to find our voices and rights as citizens taken over under the pretext of a »State of Emergency«. Newly elected members of parliament were supposed to have gathered in parliament, but they had been detained in the capital, Nay Pyi Taw. Phone lines were cut, and we were shut off from the world. History was repeating itself.

Most of the older generation has experienced something similar and has a (resigned) idea of how things will unfold, but for the younger generation, this was an unacceptable violation of human rights on many levels, especially living in 2021.

We were told to stay peaceful for 72 hours because some believed that the military was waiting for a riot to legitimize their coup. Others believed it was important to show defiance within these first 72 hours, to show the international community that the general public was discontent with the coup. During those early hours, we felt a sense of loss, were terrified by uncertainty, and filled with rage. We focused on spreading awareness through social media and seeking help from international figures whilst maintaining peace on the streets.

Already in the first days we witnessed a few political detainees including civilian government members, writers, musicians, filmmakers, student leaders, and poets. Some celebrities who had strong ties with the National League of Democracy political party (NLD, the democratically-elected governing party that was overthrown by the military coup) went into hiding.

On the third day of the coup the whole city showed solidarity against the military using various methods of nonviolent rebellion; banging pots and pans, honking car horns, and civil servants refusing to go to work. The early resistance movement was initiated by doctors in Mandalay, who refused to go to work and started the Civil Disobedience Movement (CDM) which was later joined by engineers, teachers, and lawyers. The movement gained broad public backing. The majority of us started changing our Facebook profile pictures to show support for our rightful government and to support the CDM.

Noise for Revolutions (pots and pans)

In our tradition, banging pots and pans signifies the act of driving out evil. We would start hitting pots and pans at 8pm every night. Around 7:50pm I was often already surrounded by the wave of clashing metal noises coming from the distance, which got louder and louder over the next 20 minutes. During the early days before the 8pm curfew, we would drive outside to see people hitting pots or any metal or tin object they could find outside of their homes, and we could see the determination and fire in their eyes. We saw people banging various metal objects in their cars while others joined the honking cars in noisemaking.The nightly pot banging was followed by playing the song »Kabar Ma Kyay Buu« (»Until the End of the World«) which is a pro-democracy song adapted from US progressive rock band Kansas’s 1997 classic »Dust in the wind«. »Kabar Ma Kyay Buu« was originally written during the (19)88 uprising by Naing Myanmar and has been the emblem of hope and democracy in Myanmar ever since. The song came back even stronger this time around, as it was sung and played through speakers every night. Some people would sing along with grievance-filled tears and a determination to fight for those who had sacrificed their lives for democracy since the 88 uprising. Naing Myanmar wrote seven revolutionary songs during the late 1980s, but »Kabar Ma kyay Buu« remains the most well-known of them all. It encourages protesters to be fearless and to not surrender.

After the 8pm - 4am curfew had been announced on the ninth day, people continued hitting their metal wares from inside their homes. Some would even climb up to the rooftops to slam the metal, as if they were declaring their resentment to the whole world.

Our nights have never been peaceful since the coup, as the military would abduct people at nighttime. We even believe that they set the 8pm curfew purposely, so that they can sneak around easily and raid houses. Whenever they came to take away the people for »questioning« the whole neighbourhood would show solidarity by banging pots and pans and intervening in the arrest. The sound of pots and pans after the curfew became a means of alerting residents in the area that intruders are coming.

Ever since the military started to release prisoners, mainly ex-convicts, most of the time drugged and armed to disrupt neighbourhoods by poisoning the water or perpetrating arson attacks on houses, our nights have become even longer. People took turns on neighborhood watch and many townships were filled with banging pots signaling nightly intruders. It was truly nightmarish hearing all the commotion from both near and far.

We know that the pot banging movement was affecting the military when they started patrolling the streets, threatening to shoot anyone who made noise. We saw a decrease in the numbers of households who hit pots and pans due to the presence of military soldiers in neighbourhoods. Some would switch off their lights and still hit them from their rooms, continuing to show solidarity, while making it harder for the military to pinpoint where the noises came from.

The pot-banging sessions have proven to be extremely effective in many ways. Having been drained with anxiety, devastation and panics from protesting outside under the sun the whole day or from absorbing the news from Social Media all day, I think the pot banging session was the most anticipated activity during the day. That was when we felt the release of letting out our emotions, and channeling it by vigorously hitting the metals. Noise in Yangon, an experimental noise community, also started playing live from their Facebook page to accompany the 8pm noise making sessions. One can wonder how the military government would feel every night around this time as the whole nation made noises to tell them that they were unwanted, and that people wanted an end to their regime.

Music for Revolutions (songs, chants)

Music is a great means of communication and many believe that it can also serve as a powerful psychological weapon. It has been essential during battles since ancient times, when musicians and poets would accompany armies in campaigns to encourage soldiers and citizens.One powerful song that accompanied the early marches was called »Thway Thitsar« (»Blood Oath«) written by the well-respected singer-songwriter Htoo Eain Thin. He had written the song while in hiding after the 88 uprising. The vocal part was recorded later in 1991 by singer Moon Aung in Bangkok. The song has been used for anti-military rule and pro-democracy marches and activities ever since.

The influence of this marching song is phenomenal. People don’t seem to get bored of it and the lyrics and melody get stuck in your mind, the beat of the song sends your heart racing and your blood boiling. It united the people. The song is often looped and performed repeatedly, further increasing its energy and bringing people together.

Whether small groups marched the streets or large groups protested at major gathering points, music was an essential component played in between protest chants. We knew this would be a long battle and it was not easy to protest all day under the scorching sun. Protesters need some kind of entertainment; some songs to keep them motivated, focused, and to elicit a sense of belonging. A song such as »Khun Arr Phyae Meenge« (»Don’t give up little one«) by another respected singer-songwriter, Khin Maung Toe, is very comforting to sing and hear, and tells us to be resilient. While the people were protesting, there were always those that provided generous support by means of food and beverages, and showed solidarity.

A few days into the early non-violent protests, we discovered that some had brought their snare drums to accompany the chants, which sounded especially great when the protesters sang the »Thway Thitsar« song. The sound of the snares empowered each protest chant, accompanying our demands and the ultimate wish to end military rule. Having a rhythm always kept things flowing.

To get international media attention and to keep the protests fresh, those of the young generation came up with innovative protest tactics; creating different themes, trolling the police, dressing up into eye-catching outfits, creating very bold protest signs which went from displaying deep messages to rather funny ones.

Since music and performance acts were also methods of peaceful protest, artists and musicians began providing live performances to energize the crowds. Celebrities would hold megaphones and lead chants, using their influence to attract larger crowds and to keep people motivated. This in turn put them at risk of being put on the arrest warrant list, since the Military targeted the protest leaders.

There were also many street performances around major gathering points; rappers were freestyling and protesters came out from the crowds to join them, dancers were performing, poets were reciting their emotions and discontent, performance artists were expressing their feelings towards this injustice through their bodies, and musicians were amplifying the protest chants and revolutionary songs with their instruments.

As the Civil Disobedience Movement escalated, we knew that it was a really effective tactic to cripple the Military government, in addition to boycotting their businesses. Some protesters came up with different ways to cause traffic to prevent non-CDM civil servants from going to work, while others tried to persuade them to stop going to work.

As the demonstrations against military rule got creative with humorous acts, some of the public began to fear that the protests would start to look like a festival, that they would lose focus and stray from their original goals. Others believed that creativity and a sense of humor was a great way to get international attention. They also believed that it was important to add an element of fun in these movements because it was a long battle and without any entertainment, people’s motivation would die off easily. The conflict between those two mindsets continued for a while but one thing was certain: people still decided to be out on the street despite the rumours and warnings of violent crackdowns from the police. They all had already taken a risk of being targeted.

Because of warnings of police crackdowns, most music performers keep their set-lists short, and move around between different major gathering points to perform. There was one interesting revolution song, written with an orchestral arrangement, that came out in early February, called »Revolution« by GenerationZ MM group. With its revolutionary words and bass drum, it sounds like battle music. That really set your mind to fight and served to prepare you well for what was coming. This was the type of song that makes your hair stand on end. What was more amazing was that, a week later after the song was published, the group decided to perform live in two major points in Yangon. It was a huge and risky challenge considering the size of the band; up to 30 instrumentalists and a choir of about 20 members. But they did so quite smoothly and briefly. Witnessing the performance for only 10 minutes gave us a lot of courage and strength, and brought some people to tears as they were reminded of the need to put an end to the injustices against us at any cost.

Later in February, a really upbeat song which has more positive energy in it came about and it is called »A lo Ma Shi«(»We don’t Need«) and it became widely used during protests. It has a sense of persistence in the melody and lyrics, and a rhythmic sound of clashing metal that was fun to clap along with, and which kept protesters entertained and high-spirited.

The Mizzima TV channel on Youtube would broadcast the revolutionary songs live, starting off with »A lo Ma Shi« at 8pm, which is perfect for those who protested with pots and pans indoors. I remember singing and dancing while hitting the metal plate rhythmically with the song.

Deadly crackdowns in Yangon took place a bit later than in other major cities, and as the death tolls increased and the crackdowns got more violent, we saw the street performances disappear, and large long gatherings split into smaller rallies along the streets. Instead of meeting at major gathering points, each township[1] hosted protests while putting up barricades in the streets to slow down the police, securing the neighbouring houses to cooperate and allow protesters to hide inside in case the police began chasing them. Those protests were again accompanied by the sound of snare drums. Songs such as »Thway Thitsar« and »Alo Ma Shi« were played in between chants while protesters would clap along to keep the flow going. Our goal is to make each protest powerful, and as safe as possible. There were also a few pop up performances in some neighbourhoods; very quick sets of just a few songs, often accompanied by poets expressing their rage, as well as someone scouting the perimeter or barricading the streets.

Digital Tactics and Global Activism

As our digital protest and global awareness of our situation very quickly gained momentum, particularly on Facebook, the official ban on social media in Myanmar was issued on the fourth day of the coup. We quickly adapted by learning to use VPNs (Virtual Private Networks) to access those banned apps and platforms. We could say that this very same day was the beginning of our revolution; a group of youth initiated an anti-junta protest led by Dr. Tayzar San, a well-known physician in the country’s second largest city, Mandalay.Many youth-led movements took on digital formats, not least because of safety concerns; coming face to face with the police during a crackdown is an unfair fight, since they have weapons and we only have makeshift tools to defend ourselves. After losing many lives to the military we have to come up with smarter ways to ensure our safety. An operation called Hanoi Hannah began, with the objective to blast audio files where soldiers can hear them, all the while retaining a safe distance to prioritize the safety of the person carrying out the task. Operation Hanoi Hannah believes that after some time, the minds of the soldiers will give in to the messages included in these intriguing audio clips, so that eventually the soldiers will join the Civil Disobedience Movement and the citizen’s fight for freedom. Each audio track consists of a script aimed to bend the minds of the soldiers – to shame them, to frighten them, to guilt trip them – narrated with agony by voice actors over daunting background music. These audio creations can definitely capture your attention from beginning to end. The operation’s name itself was inspired by Hanoi Hannah from the Vietnam War[1].

Another similar campaign is 100 projects, where people use projectors to display 10-minute videos compilations of artworks, illustrations, photographs, and video clips related to the revolution. The videos are screened indoors, and outdoors on buildings, landmarks, and public spaces. The nationwide campaign now also includes participants from other countries who are against Myanmar’s military rule.

Digital activism became another safer and effective movement that grew after witnessing the atrocities caused by the military; artists began streaming online live performances, and sharing new revolutionary songs or thought-provoking posters and illustrations.

One great example of digital activism is an initiative called Rap Against Junta, a creative resistance movement consisting of MCs, producers, DJs, sound engineers, event organizers, and graffiti artists. Most of the artists used their acronyms when releasing their songs, but there is one bold artist named Floke Rose who would release under his original artist name, despite already being on an arrest warrant list; an example of a fearless defiance. The initiative released a song named »Dictators must Die« by Floke Rose and Cori Rey from Myanmar, in collaboration with artists from Indonesia, India, Taiwan, Thailand, and Hong Kong. This movement allows artists from across the globe to unite and help spread the message, which contributes a great deal to bringing about social change.

Thanks to netizens from Hong Kong, Taiwan, Thailand and Myanmar, an online multinational movement to advocate democracy, called »Milk tea Alliance3,« was also born. It was originally an internet meme created in response to Chinese nationalist comentors on social media but had evolved into a »leaderless protest movement pushing for change across Southeast Asia.« On the 28th of February, Myanmar held a Milk Tea Alliance day strike and received solidarity support from the three founding regions Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Thailand. The movement also gained support from South Korea, Philippines, India, Malaysia, Indonesia, Belarus, and Iran.

Another gesture of showing resistance and solidarity is a three-finger salute, originated in the Hunger Games film which was first adopted by Thailand and now by Myanmar as well. Having a symbolism is also integral during a revolution as they are difficult to ban completely and just seeing someone raising a three finger salute gives you extra energy and returning the salute reinforced the solidarity and your defiance.

Being a noise musician myself, hearing my city making noise, hearing the dings and clashes of metal from the horizon, was the most satisfying and stimulating moment in the early days. Now, months into the coup, one can hardly hear these sounds due to the presence of informants and soldiers. The absence of that wave of noise is indeed a bit discouraging, and now more and more people are calling on everyone to unite again to rekindle this movement.

The sound of our protest is an absolute defiance, it is anything and everything to end the dictatorship. The sound of the asynchronous steps in a march, the rhythm of the chants, the beats, the metal noises, the symphony of horns from cars, the revolutionary songs, the voices, the frequencies, are all the sound of resistance. While some people may have lowered their voices, or while some may have fallen silent, there’s always a note that lingers. The sound of resistance can ignite the fire within us and can unite us.

[1] Cities in Myanmar are divided into townships, which further subdivide into districts and wards. Yangon is made up of 33 townships.

[2] Hanoi Hannah is the nickname given to a woman who became famous among US soldiers for her propaganda broadcasts on Radio Hanoi during the Vietnam War.

[3] Milk tea is a popular drink found in the founding three countries; Hong Kong, Taiwan and Thailand. The late members, Myanmar and India, also share variations of milk teas.