Dubai is the teenager among the world's cities. And soon to be the most sustainable and happiest city of all. How so?

At 456 meters above the ground, the city’s outskirts remain hidden. Highways, construction cranes and high-rise districts of reinforced concrete and glass are lost in the haze of desert sand that lies above the city. Let me welcome you to Dubai from the 125th of Burj Khalifa, the world's tallest building.Dubai is one of the cities with the highest ecological footprint. That makes sense given that it is located in a desert where summer temperatures can reach 49 degrees, requiring continuous usage of air conditioning.

Not to mention the population's rapid growth. In 2023 alone, over 100,000 people moved to the area. The population of the city rose by 50,000, to 3.6 million at the beginning of July, which explains the ongoing constructions. And it’s well known that construction work is the number one climate killer. This is no different in Dubai than anywhere else in the world.

A big promise

Dubai, however, sets itself apart from other cities with a great promise that, in 26 years, it would become the world's greenest, happiest metropolis, with the lowest environmental impact and the best quality of life. This is what Dubai, one of the seven emirates that make up the United Arab Emirates, aims to achieve.How does Dubai intend to achieve this objective?

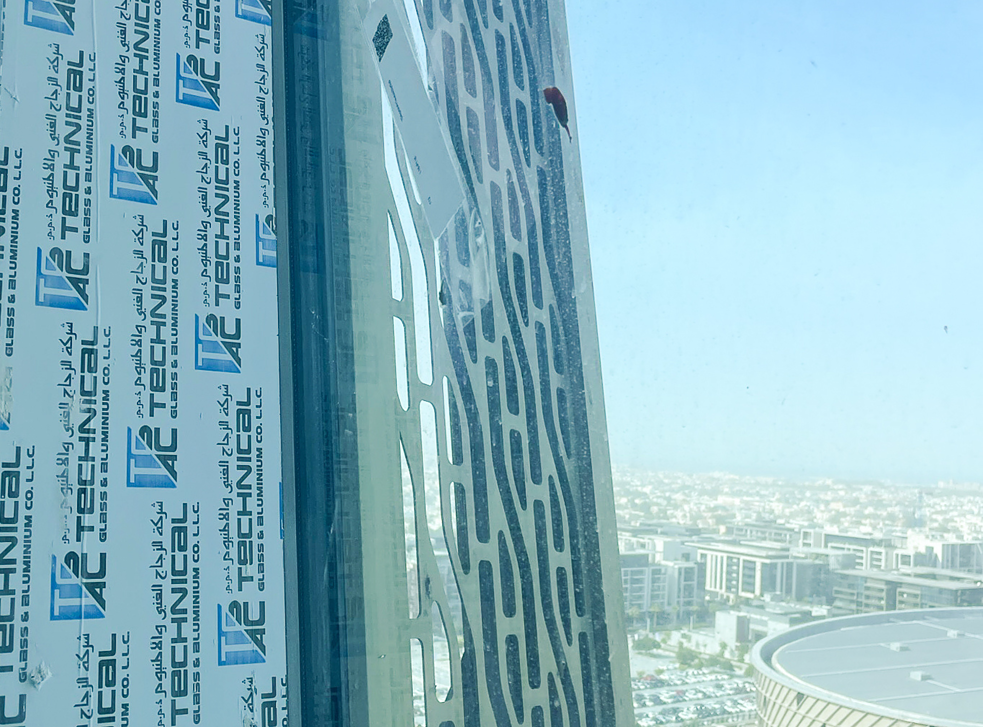

Part of the answer is provided by the Wasl Tower. It is roughly 302 meters high and has 64 stories, the upper of which are currently under construction, which explains why there are three rotating cranes on the roof.

It’s mid-November; in three weeks, Dubai will host the COP28 Climate Change Conference. A radio ad is highlighting the value of sustainable building, while a newspaper article describes the Wasl Tower as “The Beacon of Sustainability in Dubai”.

In Germany, the Wasl Tower would be the tallest building, in Dubai it would be 32nd. | © Jonas Mayer

Not enough sun on floor 15

Meanwhile, there's an issue on the 15th floor of this much-praised tower. Nick Marks, the senior architect on the site, addresses two installers saying: "I would like a report explaining how this occurred and suggesting the best course of action".They have solar-powered hot water panels installed along the south-facing windows. However, because of their high mounting, they only receive two hours of sunshine per day at most. The Dutchman Marks from the Dutch office UNStudio has been working on the Wasl Tower for nine years, together with the engineers of Stuttgart architect Werner Sobek.

Nick Marks has been working on the Wasl Tower for nine years. It should be six. | © Jonas Mayer

Passive facade

A shadow falls on the window. It is of one of thousands of ceramic fins protruding from the façade next to most of the windows. They reflect and dissipate just enough sunlight to save both air conditioning and artificial lighting.This technique is known as "Passive Design," and it involves planning buildings so that passive cooling occurs naturally without the need for additional technology.

Or constructing like the ancestors did 200 years ago along the Khor Dubai. At that time, traders settled on the Gulf coast and founded what is now known as Dubai. They built houses that serve today as models for desert architecture.

Corals and wind towers

Al Fahidi and Al Shindagha neighborhoods have been renovated. Tourists are wandering the alleys, shopping for scarfs, spices, or souvenirs with Arabic calligraphy , while two men are making their way to the mosque.Despite the midday sun, many alleys are shaded by the houses. They are two-storey building with courtyards over which awnings are stretched at noon. The walls of the houses are built of clay and coral rocks and feel rough and warm. The heat of the day is stored in tiny holes inside the stones waiting to be released at night.

The ancient builders of Dubai pulled the coral stone out of the waters of the Gulf. | © Jonas Mayer

This is what Dubai and the six other emirates looked like and how they adapted to the heat until the 1950s.

A new American Dream

But then came the oil. With oil came wealth, and with wealth came immigrants together with the need and money to build huge cities from scratch.From 33,000 in 1960 to 3.6 million today, more people live in Dubai than ever before, with 3.3 million of them being immigrants from around the world. Millions more are probably on their way, all seeking the “New American Dream” that is being fulfilled here.

Dubai itself is willing to welcome all of these immigrants. "A Land for Talent" and "The Business Capital" are two of the eight guiding principles developed by Sheikh Mohammed Bin Rashid Al Maktoum for this emirate. Dubai is expected to be the world’s innovation engine, a multi-industrial hub that is resilient to global crises and not solely dependent, as in the past, on the oil sector.

The Burj Khalifa is the symbol of Dubai's rise. | © Jonas Mayer

Dubai is a mix of cities

"Enjoy the empty streets while they still are," a broadcaster says commenting on a report stating that Dubai has emerged as the place that immigrants choose to settle in.The city's highways have many lanes and run along and across neighborhoods that seem to be on different continents. You get the impression that you are in Manhattan when you are in Downtown; the streets remind you of Mumbai, and the narrow and colorful buildings of the canal houses in Amsterdam. It has a little bit of Beverly Hills, Singapore and London too, and a lot of golf courses. Hardly much gives you the impression that you are in what will soon be the world's most sustainable metropolis.

"The country next to Saudi Arabia"

Huda Shaka grew up in Dubai. In 1999 she moved to Lebanon and then to California to study. She would tell people that her country was "the country next to Saudi Arabia", and always thought she there was little chance to have a career as an architect in Dubai.Shaka, however, came back and started working as a planner and consultant for sustainable cities at Arup, and, as of this year, at Gehl – two of the world's most renowned companies in this field. Master plans for the future of Dubai, Abu Dhabi, and other emirates have been co-designed by her. She often speaks at conferences about sustainable urban development in the Gulf region, including at COP28.

Huda Shaka is also known in Dubai as "The Green Urbanista". | © Jonas Mayer

Shock in October 2006

"Dubai's interest in sustainability came in waves," she says, "and the first wave came out of a shock." In its Living Planet Report of October 2006, the World Wildlife Fund WWF listed the United Arab Emirates as the country with the largest ecological footprint per capita, primarily due to the country's construction industry.The world's tallest tower, the Burj Khalifa, and the biggest shopping center, the Dubai Mall, were both still under construction at the time. the first batch of the thousands of villas on the artificial Island of Palm Jumeirah had just been handed over to their wealthy owners and much larger artificial islands were planned. "Dubai was portrayed to the world as an ecological sinner," says Huda Shaka.

Building green according to regulations

In 2008, the emirate announced mandatory standards for sustainable environmental construction. These standards were based on the internationally acclaimed LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design) scale and adapted to suit Dubai’s climate."In Dubai, the focus is on energy efficiency for cooling - just like in Germany for heating," says Thomas Kraubitz. He is an architect, urban planner and co-founder of the German Sustainable Building Council (DGNB), whose certification system he helped to design. He has already worked with around 20 different certification schemes for sustainable buildings and cities around the world, including in Dubai. "Labels or certificates don't make sustainable buildings and districts," Kraubitz points out. "But they do ensure reliable quality - and of course they also help with marketing."

Today, the Safaat Green Building regulations stipulate that environmentally superior buildings must have a green roof, solar panels for hot water, or be constructed using low-carbon concrete.

The neighboring emirate of Abu Dhabi started building "Masdar City," the first carbon dioxide-free city, in 2010, signaling the start of the second wave. The city was intended to be the world's first car-free, CO2-neutral metropolis with an abundance of solar panels and shaded façades. Due to the increased awareness and information surrounding this topic brought about by the creation of "Masdar City," Dubai was interested in developing complete sustainable neighborhoods rather than single structures.

Dubai's eco-district

Indeed, a “Sustainable City”, was built on the outskirts of Dubai. The name already indicates the concept: it is a residential area that can accommodate up to 3700 people, with bicycle paths, greenhouses, donkeys, ducks, and two giant tortoises named Sonny and Shelley.Under a wind tower, a woman lies asleep on a bench in the center plaza. All of the electricity needed in the area is produced by solar panels mounted on carports and rooftops.

Traditional and modern

Ahmed Bukhash arrives at the office 45 minutes late. The thunderstorm at night left roads and parking lots under water. This occurs two or three times a year, he says. Bukhash points out the window: "See how clear the skyline is today."The outlines of the Burj Khalifa stand out sharply against the bright blue sky, surrounded in every direction by dozens of other skyscrapers, including the Wasl Tower which is still under construction.

Ahmed Bukhash is helping to build and plan the Dubai of the future. | © Jonas Mayer

Ahmed Bukhash was wearing the traditional white robe; the kandura, and the so called ghutra. He is one of the few well-known architects from the UAE. In 2009, he established his firm "Archidentity" with the aim of fusing ecological, traditional and architecture.

Two cardboard models on his table aptly reflect this goal. Each one features a grey and white house with sharp outlines. The inner courtyards of the residences are high and narrow, with few wide windows.

His customers now often ask him about traditional designs, he says. “But they often don’t realize that wind towers cool the houses too, and don’t just serve aesthetic purposes.”

A plan for 2040

"The lockdowns during the Covid pandemic have made us think again about life in Dubai , about all the space for car traffic," says Bukhash. "Now we want to do more for pedestrians, cyclists and public spaces."He works for the Dubai Development Authority as the Director of Urban Planning in addition to being an architect. He co-designed the master plan for Dubai in 2040 under the motto "The Best City for Living in The World". A few examples of the master plan's provisions include requiring all residents of Dubai to live no more than 800 meters from a metro station and doubling the green spaces.

Ahmed is 100 percent confident that Dubai is on the right track.

The Dubai of today is built for the car. | © Jonas Mayer

The beloved metaphor

By 2050, 75% of Dubai's energy will come from renewable sources. Eight years ago, the Sheikh of Dubai declared: "Our goal is to become the city with the world's least environmental footprint by 2050."Huda Shaka says: “Thanks to Dubai’s and the United Arab Emirates' rapid acquisition and investment, an increasing number of hot climate regions throughout the world are already benefiting from these climate solutions.”

When asked about what needs to happen once the excitement surrounding COP28 has subsided, Shaka demands „more carrots and sticks“. She stated that after launching plans for 2040 and 2050 and establishing the Al Safaat system for green building, Dubai currently only lacks clear short-term goals for the next few years, as well as an authority to track its advancement in sustainable construction.

There is a metaphor that Dubai's architects are fond of: Paris, New York, and Berlin are like grandmothers, but Dubai is like a teenager—bold and snotty, imperfect but eager to learn.