A Portrait of Five Bouncers Guardians of the Night

It’s that tense moment when you’re standing outside a club: Will the bouncer let you in, or will it be a “Sorry, not tonight”? Apart from deciding who makes it past the doors, doorstaff are also responsible for ensuring that party-goers feel safe all night. Jonas Höschl and Sascha Ehlert portray five nightclub workers who together have over 50 years’ of doorstaff experience under their belt.

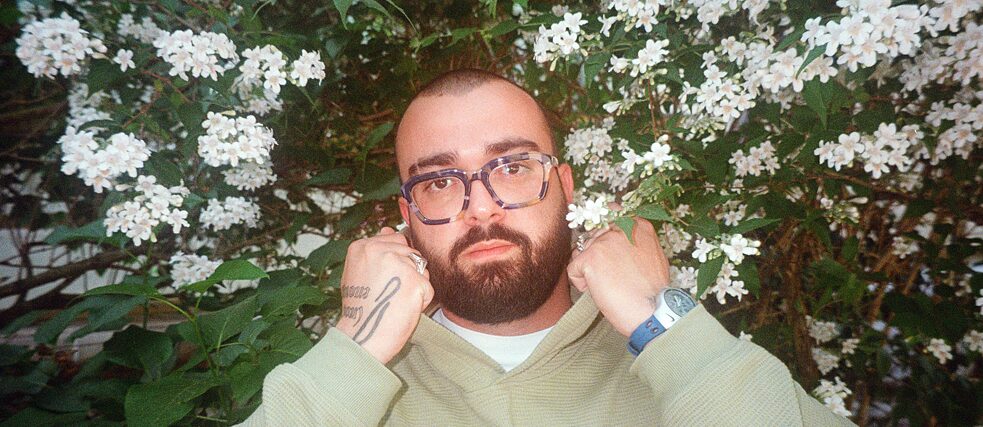

Killa Schuetze, Robert Johnson (Offenbach) & Tresor (Berlin)

Sascha Ehlert: Did this job come to you – or did you come to the job? And when and where did it happen?

Killa Schuetze: You could say the job came to me. That was in 2008, in Frankfurt am Main. I’d just got back from Portugal and needed work. Back then, I was part of a close circle of friends, and a lot of them worked at the Robert Johnson. When one of the women got pregnant, I was asked if I wanted to take her place.

Did you get used to the work quickly or did you have to develop a thick skin first to be able to deal with all the experiences you had at the door of a techno club?

Both a bit. Obviously, when you start out as a bouncer, you have certain preconceptions about the job, and at first you try to live up to them. You don’t have formal training or anything like that beforehand. It’s all about learning by doing. But all the people working at the Robert Johnson at that time were friends, so it all happened very naturally.

To what extent has this job shaped you as a person, and how much of a club-goer were you before?

In the 1990s, I used to go to hip-hop clubs in Frankfurt and the surrounding area. Then in around 2000, I started going to house and techno clubs like Monza or the Robert Johnson. Then I lived abroad for a few years and I didn’t go out much during that time. It was only when I came back and suddenly landed this job at the Robert Johnson that I started getting into techno and house culture. And it was only then that I started understanding what subculture can achieve – and how much you can be part of this change yourself, for example as a woman bouncer at a club door like that.

From today’s perspective, how did the Robert Johnson’s decision to work with a female door team impact Frankfurt’s nightlife at that time?

I think this was one of many small steps towards equality in club door policies. The Robert Johnson wasn’t the first club to do something like this. The legendary Dorian Gray at Frankfurt airport also had a female bouncer. And around the same time in Berlin, women were also starting to get door jobs. But it has definitely progressed since then, so it’s now relatively common for people who are perceived as female to work on the doors.

We’re always sober and on guard.

That’s a good question. First of all, of course, it doesn’t usually feel like we’re part of the party. We’re always sober and on guard. And we have a certain responsibility to ensure that the people inside, the ones who want to behave freely, have fun and who aren’t sober, are safe. We’re also in a different room from the group of people who don’t want to “be careful”. Nevertheless, we still feel like we’re part of the party. After all, we see each guest twice an evening. And the second time, when they leave, they usually look very different to the time when they arrived. Ideally, you can tell they’ve had a great night out.

So in a way you’re like Cerberus guarding these clubs, these spaces that are, to some extent, detached from reality.

That’s really how I feel sometimes, or at least I can understand the metaphor. Guests cross a kind of threshold when they come in – and that also means a change of consciousness, regardless of whether this is triggered by the room, the music, the dancing or drugs.

You told me during our initial talk that you quit the Robert Johnson when the pandemic struck and then didn’t work as a bouncer for a while before you took a door job in Berlin. How did it feel for you in that in-between time, without the routine of working nights at weekends?

Actually, being a bouncer has always only ever been a small part of my life – as it was for most of my friends back then in Frankfurt. Everyone was sort of studying, had part-time jobs or were involved with art, and they were working on the doors just to do something different. But the pandemic was a tough time for many because clubs aren’t businesses in the traditional sense. The people who regularly work there usually do so on a freelance or mini-job basis. So it’s not the kind of job where you’re covered by social security, where you work reduced hours or anything like that. It’s different in some big clubs, of course, but most club workers have very precarious employment. This was a really hard time for me as well, but I did finish my degree in photography at Folkwang University during that time, and I really enjoyed being able to immerse myself completely in my art. Then came the job offer from Tresor.

Were you aware of the club’s background when the invitation came?

I had no reason to find out about Tresor before, but when I came into contact with the club, of course, I soon heard all about it. It quickly became clear to me that a club like Tresor needs an anti-harassment team. So while I was at Tresor Berlin and Tresor.West in Dortmund, I set up three teams and linked them with each other. There are the security people, the guest selection or crowd management people and the anti-harassment team. In the past, clubs usually had one team that was responsible for all three roles. On the one hand, we were the crowd managers, in other words the ones who decided who to let in and who to keep out. But we also checked bags and kicked out people we were uncertain about. Or called an ambulance if someone needed one, settled disputes, and so on. I’ve tried to set the teams up so that they each have their own responsibilities, but the boundaries are still fluid. And it’s not just the club workers but also the managers who have to learn and actively practice anti-harassment policies, so that everyone works together and everything runs smoothly. This are usually the biggest hurdles.

More professional structures are being implemented to ensure that all people – without exception – feel comfortable in clubs. To what extent has this changed the parties themselves? Or is this not the case at all?

What really has changed is that more and more people have reached the point where they’re saying, enough is enough. We don’t want to be sexually harassed when we’re out at night or experience discrimination at night club doors any more. This has meant that the standards clubs set themselves have also evolved. But at the same time though, I think we have to be clear that a space like a night club can never be 100 percent safe. All we can do is make it as safe as possible. And that also means training door staff in subjects such as gender diversity or how to address non-binary people. We also need to look at questions such as how to deal with new types of drugs or forms of consumption like spiking. Some of these issues have been around in the club scene for a while, but for a long time nobody talked about them. This needs to change. Fortunately, more and more knowledge is being shared and this helps make clubs safer for everyone.

Alex Winkelmann, Bar 25 & Kater Holzig (Berlin)

Sascha Ehlert: Alex, tell me, how did you end up at Bar 25? Was this your first door job?

Alex Winkelmann: Well, my first gig was at Kosmos on St. Pauli in Hamburg. I used to live in Hamburg and I worked there with a girlfriend. When I moved to Berlin, she was already there and already working at Bar 25. She said if ever I needed a job, I could knock on the door – and that’s what I did. I’m bad with dates, but it must have been 2007 or 2008, two years before the bar closed. This place had growing for some time, and that’s what interested me about it. I was intrigued by this organic, improvised quality.

When I first started out, I did the cleaning and stuff like that. I just needed a job. I grew up in the restaurant and hotel trade. I used to clean rooms with my mum when I was a kid, so I found it really easy. I learned at a young age that it’s worthwhile doing these jobs conscientiously and carefully. This was why the people at Bar 25 learned to trust me. Eventually, they put me on the backstage door, so I was checking who had a wristband and who didn’t.

This was the first time I had some pretty tricky moments, for example when people didn’t have a band but were desperate to get in for some reason or another. Some of these people were really big, and I was a complete joke by comparison. Most of them, though, found it funny when a person like me said “no” to them. But, of course, there were some people who also got incredibly upset. That’s when you have to try and talk to them. Fortunately, I never got punched in the face or anything like that.

So are you good at de-escalating difficult situations?

I’d say I’m generally a pretty calm kind of person. I’ve always tried to keep cool during conflicts and find a solution, like suggesting to guests they call someone who can vouch for them, or something like that. Anyway, Bar 25 eventually moved to the other side of the Spree and called itself Kater Holzig. That’s where I started working on the front door cash desk. This was a job that required even more trust. My shifts often went from 10pm to 6am or so. Sometimes, of course, they were even longer, like on New Year’s Eve.

At some point, I started doing the cash desk on Sundays, when people came to Kater all day long. Usually, the same people came to the club, so they were always allowed in. A lot of the crowd that came to Kater on Sundays had been out partying for a long time, so of course I’d ask them where they’d come from, check them out a bit. There definitely wasn’t an agenda or anything – apart from the fact that we welcomed people who like to party for a long time, so people with a certain vibe. Otherwise, we just wanted people who seemed nice and relaxed.

In the night club profession, it’s not so easy finding trustworthy people.

More the latter. Well, I did find the place fascinating. It was a kind of temporary autonomous zone, completely out of control. And it was exciting to see the momentum that developed. But I wasn’t a raver when I came to Berlin. I’ve generally been a late starter all my life; it’s the same with partying and drinking. While I was working in nightclubs, I tended to be more the silent observer. It was only at the end, when I was allowed to host my own events, that I gave up that position. In retrospect, this was probably why they trusted me with so many things. Eventually, they assigned me a budget so that I could curate my own parties, also because they liked my music. I never stole anything or did anything like that – in the nightclub business it’s not easy finding trustworthy people.

When and why did the Bar 25 or Kater Holzig chapter come to an end for you?

I worked there for altogether four or five years. Obviously, I saw some good and beautiful things, but I also experienced the ugly sides of the job, sometimes even the dangerous ones. In any case, I started to realise that working nights – I was doing it two or three times a week back then – wouldn’t be good for my biorhythm in the long term. I was kind of okay with it for a while, but I didn’t see myself in this job for years to come. Then another job came up when friends of mine opened their own place. That’s when I started working at Heimathafen Neukölln, a traditional live venue, behind the scenes. Like I said, I grew up in the hotel business, so I think I’ve always been happy “serving” and being nice to people.

Steffi-Lotta, one of the founders of Bar 25, asked me if I wanted to do the guest selection on Fridays and Saturdays, but that was too much for me and I turned her down. Then I did my last shift there, which was really cool. Actually, there was always a good community at this club. If you were part of the inner circle, it was great. I’m still friends with the people who used to work there today. When you do such a long shift together, when all this stuff is going on, it’s obviously exciting and always fun. Nevertheless, I made my exit in the end.

Did the end of your job mean a break with this social cosmos, or has it remained part of your life?

I still see people I met during that time. I occasionally have these flashbacks when I go to some bar or Modulor on Moritzplatz and bump into a guest there. We might just look at each other in surprise and not talk. But I don’t make a point of going back to my old workplace, or what is today the Holzmarkt area. I did once, four or five years ago. Everyone was really friendly and welcoming. But generally speaking, this period of my life is over for me, and I rarely go out partying any more.

What’s left of Bar 25?

We shouldn’t romanticise Bar 25 too much, obviously, but it really was a very open and free place. And I think we still need places like that. I’d say I grew up in a relatively unconventional environment – at least, my parents were always a bit critical of everything that was conventional. I think that’s why I’m good at adapting to unconventional places. I’m also very flexible and open in terms of social norms. And that’s what Bar 25 was all about. It was definitely a place where you could try out new things. I loved being able to go through so many different phases there. And, of course, places like that are important for a city. Places where you can switch off a bit and move freely. Environments like this are important for people. This is something my job made me very aware of. And people don’t necessarily have to be on drugs. Clubs like this are also social meeting places that really mean something to people. I think it’s great that I could contribute to this.

Hanna Teglasy, petersplatz.eins (Vienna)

Sascha Ehlert: How did you end up as a door supervisor and what do you actually do there?

Hanna Teglasy: The club I’m working for opened on New Year’s Eve in 2022, and I do more than just work on the doors there. I also help with the bookings and do social media. But in the evenings, I usually work at the front desk, so I let people in and do admissions. Because of the fact that I’m involved in many different ways and therefore have a certain position of power, I made a conscious decision to work on the front desk too. Just sitting at a computer writing emails and making phone calls is somehow not my thing. Besides, on the doors I find out what’s going on, I get to know our patrons and see for myself how they’re feeling.

So you treat them as equals. Are you a club-goer – would you be going to these parties yourself if you weren’t working on the door, collecting money?

Yes, definitely. Even if I do this less frequently now that I work in the club. But I’ve always had friends who organise parties, make music or are DJs, so I’ve always been pretty heavily involved and interested in the clubbing scene.

What made you decide to work in the club?

The team. They’re a bit like family for me. We talk very openly to each other. I can tell the others if I’m not feeling great – someone will always step in for me. I don’t have to explain myself; it’s quite normal for us to help each other. I really value this close kind of partnership. I feel very comfortable with the others.

What do you do to make the people who come to the club feel comfortable?

The main thing I do is try and communicate very openly. If I have someone in front of me who I think has had a bit too much, then I try to engage with that person. I ask them why they’re here, invite them to sit down and give them a drink of water. And people I don’t think are a good fit, I’m just very honest. I say, “Don’t expect to come back in five minutes and ask for your money back”. I feel if I’m honest with them, they are also honest with me – for better or for worse. Obviously, there are also situations where you have to throw someone out – and few people, especially men, react positively to that.

Clubs are traditionally places that give people the chance to abandon themselves for a few hours. They are spaces of dissociation where social norms seem less important for a while. Is this an idea that still holds true for you personally?

I’d like that to be possible, but too much sexualised violence still goes on in our society in the context of parties. That’s why we, the club, need a good control system in place so that everyone in the club still feels comfortable at the end of the night.

Now that you work at a club yourself, do you still go out clubbing in other cities and countries?

I don’t go out privately in Vienna much, as I said, but I love to in Budapest. That’s actually where I’m from and why I go back there once a month. Obviously, there’s some ambivalence about it all, when you look at what’s going on in Hungary politically at the moment. But the reality is, when the state controls people too much, a strong underground culture emerges that offers people an alternative scene. While Vienna Pride feels like it’s become just another event where straight men go to get pissed, the queer parties in Budapest are organised by a strong community. You can sense the love and urgency behind it all, and the whole thing is often financed exclusively by donations. I think we’ve become quite hypocritical here in Vienna when it comes to partying. There’ll be a climate rave, but at the end there are tin cans everywhere.

I wanted my last question to lead to a follow-up question. I’d like to know if you can explain what defines Viennese club culture? Is it different from other, especially German-speaking, cities?

One thing that really is special about Vienna is that there are so many outdoor events, for example on the Donauinsel. In the summer, you can party everywhere – I haven’t seen that in any other city.

Everything is political, even partying.

Well, places like that do already exist here. On the other hand, though, there are also events where you might think, okay, everyone treats everyone else respectfully here, but then something unpleasant still happens. It’s a completely different matter again in mainstream clubs. My problem with nightlife in Vienna is that there are safe spaces, but as soon as you leave these and go out in the public sphere, you’re automatically exposed to certain dangers if you’re not heterosexual or cisgender. I believe everything is political, including partying.

You might not have been working in a nightclub for very long, but I would still like to ask you if you can imagine staying in this line of work in the next phase of your life – or do you see it more as a temporary job?

I think it’s more the latter. This job does take a lot out of you. I mean, no matter how great the parties and the people are, I’m talking to 300 or 400 people every night. And then there’s the fact that I soon realised that ultimately, nightclubs are really only about money. But there are lots of positive things too, of course. I’ve met loads of amazing people. But every so often, I have to drag myself away from this lifestyle and simply recharge my social battery. I’m sure I’ll continue to have something to do with club life. But maybe more behind the scenes. That’s where I can see myself in the long term.

Daniel, Celeste (Vienna)

Sascha Ehlert: What made you become a bouncer?

Daniel: I’d just finished school and had nothing better to do when I was offered this job. I’d just started studying but was looking for a part-time job anyway. Working as a bouncer fits in well around that. So it just kind of happened. But I was lucky to have one important qualification: that I’ve always been quite good at resolving conflicts in a non-violent way.

What is your strategy for managing disagreements and resolving conflicts in nightclubs?

Well, my maximum use of physical force is to push someone a bit. This is my basic principle, so in general I handle confrontational guests differently. I usually try to stop the confrontation even before it starts. After 15 years in the business, I’ve realised that if you don’t do that, you soon end up in a spiral and things escalate. In actual fact though, these sorts of incidents rarely happen to me in the clubs where I work.

Since COVID, the club scene has changed quite radically. For example, an increasing number of clubs are appointing anti-harassment teams to ensure that everyone in the club can have a good time without having to be afraid of male guests, for example. How has your work practice changed in the past few years?

I have worked in the same club for ten years. It’s been in existence for 30 years, and was a restaurant before that. Ten years ago, the owner’s son took over and turned it into a club. I’d actually stopped working as a doorman by then. I’d finished my studies – but then the partner of the guy who opened this new place asked me if I wanted to work on the door. He called me because on one occasion I’d kicked him out of another club. He was apparently impressed by the way I handled him.

In any case, since I’ve been working there, we’ve always followed the same philosophy. The most important thing of all is to respond immediately if someone feels uncomfortable – and immediately throw out people who is causing trouble. Basically, though, we have a pretty easy-going clientele. The kind of people who come here know what to expect. They come here specifically, they’re not passing trade. Of course, you have to be tactful as a bouncer, but it’s pretty easy here if you’re good at communicating.

Being a bouncer is easy if you’re good at communicating.

There are many different reasons. I’m not someone who goes out privately. But what this job with its flexible working hours has brought me is a fixed income and also social security in the Austrian system. It has enabled me to develop in several directions simultaneously. I can also take care of my two grandmothers, for example. I have enough time to spend 20 hours a week with them, which of course wouldn’t be possible in a “normal” job.

I’m also really passionate about making things. I like restoring things like bikes, gramophones and instruments, which I then re-sell. Working on the door also has a social dimension. You go out for the evening, as it were, and get paid for it. I just have to be myself when I’m there; for me the job is not especially stressful. There’s probably nothing I can’t handle during my shifts on the doors.

You come into contact with an incredible number of people in your job. Have you ever had an encounter that was particularly memorable for you, or which changed your way of thinking in some way? Have you ever met someone on the doors who you’ve become close friends with since?

Yes, my social life has developed to some extent around the club. Many of my friends are from school days, so they are longer friendships. But my work has naturally influenced my personal development and how I handle people. Every social interaction I have on the door is always a bit of an experiment for me. How am I going to deal with a certain situation today? How do I start a conversation to decide who to let in and who not? Should I be nice? How are my interactions affected if I’m in a bad mood or tired or whatever? To what extent does a person’s reaction depend on my choice of words? It’s super interesting.

I’m usually pretty calm – but sometimes that can be the wrong approach, too. If you’re too calm with the wrong person, a situation can backfire. I think as a bouncer, you learn a lot about the effect you have on others and how other peoples’ responses change when you change or adapt your own behaviour.

Kiki Gorei, Goldener Reiter (Munich)

Sascha Ehlert: How did you end up working on the doors?

Kiki Gorei: When I was about 19 or 20, I used to hang out at a bar in Munich, so we were regular guests, if you want. A good friend of mine started working there, and he asked me if I wanted to give it a go too. It looked fun, the staff there are cool, so I thought, “Definitely”. Having a part-time job at 19 that pays 100, 150 euros an evening, two or three times a week was fantastic. I’m 29 now and I still work every weekend.

Are you a club-goer yourself when you’re not working?

Yes, I am. I also work at various clubs as a DJ. I started doing that when I was 17 or 18. So for a long time, I’ve known lots of people who work in the same field. My friends hang out in the same places as me. It doesn’t matter whether I’m DJing or selecting guests.

When you select guests, what are your criteria?

I think I’m somewhere between strict and laid-back. I pay attention to all the usual things like not letting in all-male groups early in the evening, so that things don’t become unpleasant for other guests. The same goes for people who are too drunk or high. Generally though, I have a short chat with people and if they’re cool, anyone is welcome in the place where I happen to be working. We don’t have a strict door policy.

While I’ve been doing these interviews, I’ve noticed that the different clubs have very different philosophies and team sizes. How big is your team?

We have between eight and ten door supervisors. There are always two of us on a shift, plus someone who is in charge. So it’s actually quite a small team. We all step in for each other if need be.

What role does the club play for you as a social place?

I do spend a lot of time at the club at night when I’m not working there. And most of the time, when I’m there privately, I hang out around the door with the others.

How much has your relationship to nightlife changed over the years?

Not at all, actually. But that’s probably also to do with the fact that Munich isn’t as big as Berlin, of course. Everyone knows everyone here, and we’re all in the same circles of friends. Nightlife somehow offers me a change from my 40-hour job. It helps me chill a bit and forget about the rest of the week.

The pandemic has also helped to promote more of a community in the scene.

Obviously, there have been some COVID closures. On the other hand, though, I think the pandemic helped promote a sense of community in the scene, and to a large extent, the rigid division of genres between the different clubs, the hip-hop clubs and techno clubs, for example, have disappeared. My environment, the people I regularly DJ with and I myself have done a lot to change that. At some point, I just realised that as a DJ I wanted to play everything – regardless of whether it’s garage, trap or house. And the people who dance feel the same way.

How old is your clientele?

It’s super mixed. I’d say the people who come here are between 18 and 45.

Would you say the so-called Generation Z, so the new club generation, behaves differently at the doors and in the club than the generations before them?

Yes, I would. They’re much more polite. If I say, “Sorry, not tonight,” they’re actually okay with it, whereas the older ones like to get into a discussion.

How much has supervising the doors changed since you started? For example, do you make sure now that you have a balanced number of men and women and that you create spaces where people who are perceived as female feel as comfortable as people who are perceived as male?

In our club, I don’t think much has changed in that respect. I’m not sure exactly how we do it, but I don’t think there is any other club in Munich where so few women make complaints about feeling uncomfortable. We just make sure the people we let in are the right fit for the music style. We also have a lot of regulars who we know well.

How do you see the future? Do you ever think about quitting at some point?

I don’t at all, actually. I just really like the place. I like seeing everyone here and I generally enjoy being in the company of people.

Club culture has become an important part of Germany’s social fabric over the last few decades, and, of course, club patrons are also getting older. And so, too, perhaps the people who work on the doors. Can you imagine still doing this job when you’re 40 or 45?

Absolutely. I can definitely imagine working on the door more than being a DJ at 45.