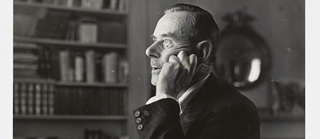

Joseph and His Brothers Thomas Mann and his Joseph in exile

Foto (Detail): © ETH-Bibliothek Zürich, Thomas-Mann-Archiv / Fotograf: Unbekannt / TMA_3035

Thomas Mann's Joseph novels are more than just a retelling of the Bible: they are a literary alternative to National Socialism - and a reflection of his exile.

The number of refugees has continued to rise. Nations must unite to negotiate a response to this development and to determine the fairest possible way to distribute these people among the individual countries. But the conference is proceeding unsatisfactorily. Hardly any country is willing to take in more people. Heads of state feel too overwhelmed by their own national problems. They believe they cannot afford to put an additional burden on rising unemployment and stoke their populations’ fears of supposed “foreign infiltration” or uncontrolled immigration.What may sound like a restrained account of today’s refugee debates in fact refers to the Évian Conference of 1938. As the Nazi regime forced more and more Jews to emigrate, 32 countries and 71 aid organisations convened at the invitation of Franklin D. Roosevelt to address the refugee crisis. Yet even the United States did not raise its quota for immigrants from Germany and Austria, then capped at 27,370 a year. “Sitting in that wonderful hall listening to the representatives of 32 countries standing up one after another and explaining how terribly glad they would be to receive a larger number of refugees and how terribly sorry they were that they unfortunately could not – it was a shattering experience. [...] I wanted to stand up and scream at them all: Don’t you realise that these damned ‘numbers’ are human beings… people who will spend the rest of their lives in concentration camps or fleeing across the globe like lepers, if you don’t take them in?” wrote Golda Meir, later Prime Minister of Israel, in her memoirs.

The privilege of writing in exile

Thomas Mann was fortunate not to be personally or directly affected by the outcome of the Evian Conference. After Adolf Hitler came to power in 1933, Mann and his wife Katia chose not to return from a holiday in Switzerland. Mann’s exile was never an existential threat. The couple had already transferred parts of Katia’s family wealth and his Nobel Prize winnings to Switzerland. Most importantly, when Mann emigrated to the United States in 1938, he did not have to rebuild his life from scratch. Thanks to translations of his books, the promotional efforts of his American publisher Alfred A. Knopf and previous lecture tours, he was already a well-known and well-respected figure. His role as a representative of the “good Germany”, which the Nazis were in the process of destroying, the Germany of intellect and culture, suited Mann perfectly. He also benefited from the support of the exceptionally influential and wealthy journalist Agnes E. Meyer, a devoted admirer and patron who strategically contributed both to Mann’s cultural impact and his comfortable lifestyle.Thomas Mann’s greatest privilege was having the freedom to write every morning – no matter how fiercely the world raged around him or where he happened to be. When he decided not to return to Germany in 1933, he was working on Joseph in Egypt, the third volume of his four-part novel cycle Joseph and His Brothers. It was a project that had been dragging on for a long time. He had started retelling the biblical story back in 1926, and two volumes had already been published. The third was meant to be the conclusion. But what followed is characteristic of many of Thomas Mann’s projects: they grew during the writing process, evolving from the idea for a novella into a sprawling, multi-volume epic. In the case of the Joseph novels, there was also pressure from the publishers for a timely release. After Joseph in Egypt – which Mann completed while still in Europe – one more volume was needed to provide a definitive conclusion to the saga. Mann, however, was in no rush. He first wrote Lotte in Weimar and The Transposed Heads. Only then, after settling in California, did he feel ready to finish the tetralogy, which opens with a second exile for Joseph. This exile is less harsh than the first, when his jealous brothers sold him off to passing merchants, who in turn sold him as a slave in Egypt. At the court of Potiphar, Joseph makes a remarkable career for a slave – until he is punished for a crime he did not commit. Yet Potiphar manages to turn this punishment into a kind of reward, sending Joseph to the Pharaoh’s prison, where in the final volume an even more meteoric rise awaits him.

An alternative vision to Nazi ideology

At first glance, the Joseph novels may seem incongruous. While Hitler was plunging Europe into chaos, Thomas Mann appeared to be indulging in elaborate depictions of biblical scenes and images in his characteristically expansive style. Bertolt Brecht, with stunned cynicism, referred to the work as an “encyclopaedia of the bourgeois intellectual”. Yet the Joseph novels were far more than a literary retreat from the realities of the time. As the novellas unfolded, they increasingly emerged as a counter-narrative to the Nazi project of constructing and promoting a mythic vision of the German people. Mann, too, created a myth – but one that belonged to all of humanity. His does not portray the mythical as a hopeless, fated inevitability, but rather as stories that embed individuals within broader, supra-individual contexts – contexts that the individual can indeed question, challenge and even change.Moreover, a personal counter-programme to the Nazis, as an attitude of resistance, finds its way into the Joseph project. Anger and rage are emotions that Mann cannot channel productively into his prose. Instead, he adopts cheerfulness as a protective strategy against the barbaric madness unfolding in his homeland. As a result, the tetralogy’s narrative tone becomes a masterpiece of expansive, playful storytelling that exploits every facet of wit. The length of the four novels also reflects the narrator’s unwavering determination to settle comfortably into a humorously softened, easy-going style.

Exile, experience, engagement

As in all his works, Thomas Mann draws richly from his own era and environment for the Joseph novels. Joseph’s role as minister of food – managing famine relief and grain storage – clearly echoes the state-directed investment policies of Roosevelt’s New Deal. The character of Joseph’s warden, Mai-Sachme, is an affectionate portrayal of Mann’s friend and writer, the physician Martin Gumpert. As always, Mann thrives on tension and the stimulus of personal experience. Joseph is portrayed as blessed – exceptionally handsome and aware of his singularity. Being thrust into a foreign culture proves to be the best thing that can happen to him. Freed from the perils of vanity, he is able to transform his uniqueness into a valuable asset for the society in which he finds himself. He becomes a mediator – a social figure capable of catalysing essential societal change, precisely because he possesses the detachment of the outsider.In this way, Thomas Mann transforms the theme of exile into a Bildungsroman, indulging in a highly positive version of his own role – a role that does not come easily to him, but one he accepts out of a sense of duty: that of the artist who understands the demands of his time and puts beauty at the service of the good. Or at the very least, he sacrifices significant portions of his writing time to composing and recording appeals directed at Germans living under National Socialism. He also undertakes several extensive lecture tours across the United States, calling attention to what steps democracy must take in order to defend itself against the fascisms of his era.