On Being Excluded Understanding the Diversity Gap in Children’s Literature

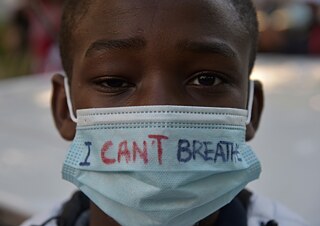

Black, Indigenous and People of Colour (BIPoC) children and the societies are depicted systematically as laughable, comical, barbaric, naïve or immoral, as beings closer to nature than to culture, as beings who are dependent on white knowledge and benevolence, writes Maisha M. Auma.

“Stories matter. Many stories matter. Stories have been used to dispossess and to malign, but stories can also be used to empower and to humanise.”

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie in “The Danger of a Single Story”, 2009

“The relation of represented Children of Colour had now sunk below the level of represented animals. There is no difficulty in representing animals, fantasy-animals and inanimate figures. There seems to be resistance to representing Children of Colour and their realities.”

The singularity written into the stories in children’s books contains problematic normalisations. The most comprehensive study of 20th century children's books undertaken in the United States; Gender in Twentieth-Century Children's Books: Patterns of Disparity in Titles and Central Characters, analysed 6,000 books published from 1900 to 2000. It was carried out by sociologists of gender at Florida State University (see McCabe, Fairchild, Grauerholz, Pescosolido and Tope, 2011). The most important finding is that when adult males and male animals counted into one category of representation they were represented as lead characters in 100 per cent of all analysed children’s books. Adult females and female animals were only represented as lead characters in 33 per cent.

Racialised marginalisation in children’s publishing shows a similar pattern of inequality: Based on descriptive statistics collected by the Cooperative Children’s Book Center, CCBC in Madison/Wisconsin (Diversity Gap Studies) since 1985, David Huyck and Sarah Park Dahlen found enormous disparities in the representation of BIPoC Children – BIPoC is an abbreviation for “Black, Indigenous, People of Colour” – in comparison to animal figures and white characters in children’s books (see Stechyson, 2019). For the year 2015, of the approximately 3,000 annual new children’s publications 73,3 per cent of the main characters were white children, 12,5 per cent of the main characters were animals (including fantasy-figures and inanimate objects) leaving only 14,2 per cent for the representation of all racially marginalised groups together. This picture had shifted in 2018 to now 50 per cent of all main characters being white, 27 per cent were now animals including fantasy figures and only 23 per cent of all main characters were all racially marginalised groups counted together. The relation of represented Children of Colour had now sunk below the level of represented animals. There is no difficulty in representing animals, fantasy-animals and inanimate figures. There seems to be resistance to representing Children of Colour and their realities.

Harmful Fictions

The representations of the social world in children’s literature are mostly fictional. They have however proved to be systematically excluding. Where BIPoC children are included, their depictions and those of the geopolitical territories associated with their lives tend to be stereotypical, stigmatising or dehumanising. Many German picture books and children’s books normalise the “white adventurer”. The German shoe label Salamander has published a comic-booklet (featuring its mascot, a male fire salamander named Lurchi, which is derived from the German word for salamander, Lurch), from 1937 to the present. In a 4th edition of Lurchi with the barbarians (Lurchi bei den Wilden) from 2019, Lurchi paints himself black (which is in effect Blackface). This is accompanied by a racist term about Lurchi becoming a N****lein (a little N****). Lurchi does this to not being cooked and eaten (see Bochmann and Staufer, 2013). The geopolitical context of his “adventure” is a BIPoC society.Other German and European examples of the white adventurer are Die kleine Hexe (The little witch), Pippi Langstrumpf in Taka-Tuka-Land as well as the Tin Tin Comics (Tim und Struppi in A****) to name just a few. BIPoC Children and the societies are depicted systematically as laughable, comical, barbaric, naïve or immoral, as beings closer to nature than to culture, as beings who are dependent on white knowledge and benevolence (see Auma, 2018). Such depictions are not only fictional, they are also harmful! They do not only deprive very young BIPoC readers of a positive self-image and positive images of their social worlds, they also force them to deal with the normalisation of their devaluation, of being overlooked or dehumanised. Young readers must “read between the racism and the harm” (see Masad, 2016). These patterns of dis-empowerment are no misrepresentations. They are toxic representations, because they cause harm to the self-worth of racially marginalised children. The regularity with which geopolitical contexts associated with BIPoC and their social lives are represented is a form of cultural violence.

Powerful Readers

I would like to close with some thoughts on initiatives, working towards more equity, race- and norm-critical intersectionality and social, economic and political inclusion in children’s literature. They want to promote the production of diverse worlds in books and other childhood media, addressed at plural, hyperdiverse societies/mini-publics. A common aim of two European initiatives DRIN (Diversity, Representation, Inclusion and Norm-Critique) and Powervolle Lesende (Powerful Readers) is to bring together key actors in the arena of children’s books production, circulation and consumption, especially towards the goal of re-centering the voices and perspectives of marginalised social groups. Four North American initiatives – WNDB #WeNeedDiverseBooks, Disability in Kid Lit, Young, Black and Lit and I am Here, I am Queer, What the Hell Do I Read?, all serve as an inspiration for the quality of intersectional justice approaches necessary, for work required in order to consistently empower diverse and marginalised young readers. These initiatives all draw on Rudine Sims Bishop’s call to create and normalise “windows and mirrors” with regard to racially marginalised young readers. Mirrors serve to empower young BIPoC readers to see themselves, their social lives and the geopolitical regions associated with their hyperdiverse diasporic realities represented as normal elements of daily narrations. “Windows” serve to close the “empathy gap” towards marginalised groups, by normalising the way they negotiate barriers and the conditions of their dehumanisation. “Windows” provide a crucial insight into the lives of all our “marginalised neighbours”, as they deal with realities, which are rarely represented in children’s media. In Chimamanda Adichie’s words, these approaches broaden the scope of the stories we tell and read. They reconnect us all in our daily struggle to affirm our own and each other’s humanity.Literature

– Adichie, Chimamanda Ngozi (2009), The Danger of A Single Story (TED-Talk).

– Auma, Maureen Maisha (2018), Kulturelle Bildung in pluralen Gesellschaften: Diversität von Anfang an! Diskriminierungskritik von Anfang an! In: KULTURELLE BILDUNG.

– Bishop, Rudine Sims (1990), Mirrors, Windows and Sliding Doors. Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3).

– Bochmann, Corinna/Staufer, Walter (2013), “Vom ‘N*-könig’ zum ‘Südseekönig’ zum...? Politische Korrektheit in Kinderbüchern. Das Spannungsfeld zwischen diskriminierungsfreier Sprache und Werktreue und die Bedeutung des Jugendschutzes.” In: BPJM-Aktuell (Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien) (2/2013).

– Decke-Cornill, Helene (2007), “Literaturdidaktik in einer ‘Pädagogik der Anerkennung’: Gender and other suspects.” In: Hallet, Wolfgang/Nünning, Ansgar (Hrsg.), Neue Ansätze und Konzepte der Literatur- und Kulturdidaktik (S. 239–258). Trier: WVT Wissenschaftlicher Verlag Trier.

– Masad, Ilana (2016), Read Between the Racism: The Serious Lack of Diversity in Book Publishing.

McCabe, Janice/Fairchild, Emily/Grauerholz, Liz/Pescosolido, Bernice A./Tope, Daniel (2011). “Gender in Twentieth-Century Children’s Books: Patterns of Disparity in Titles and Central Characters”. Gender & Society 25(2): 197–226.

– Sociologists for Women in Society (2011), Gender bias uncovered in children’s books with male characters, including male animals, leading the fictional pack. Science Daily, 4. Mai 2011.

0 0 Comments