Cultural Heritage Management Who Cares?

What is the role of conservation in a postcolonial museum? Does it allow cultural dialogue or perpetuate colonial violence? Reflections by Noémie Etienne on traces, threads and fragility.

Between September 2020 and February 2021, Claire Brizon, Chonja Lee, Etienne Wismer and myself curated a show named Exotic? Switzerland looking Outwards in the Age of the Enlightenment in Lausanne at the Palais de Rumine. The show was the result of four years of a research project. We explored the collection and storage of cultural institutions in Switzerland (art museums but also museums of ethnography, natural history, libraries, archives, etc.). We searched for material culture embedding the relationships between the Old Swiss Confederacy (today’s Switzerland with the addition in 1815 of Geneva, Neuchâtel, and the Wallis) and the world in early modern period. We discovered hundreds of objects, most of them until then in storage, sometimes in relatively poor condition. They attested to Swiss people travelling outside of the country, collecting pieces, sketching and writing, and imitating techniques to produce porcelain, lacquer, or printed cotton. Exhibition view of the “Exotic?” exhibition

| © Lionel Henriot

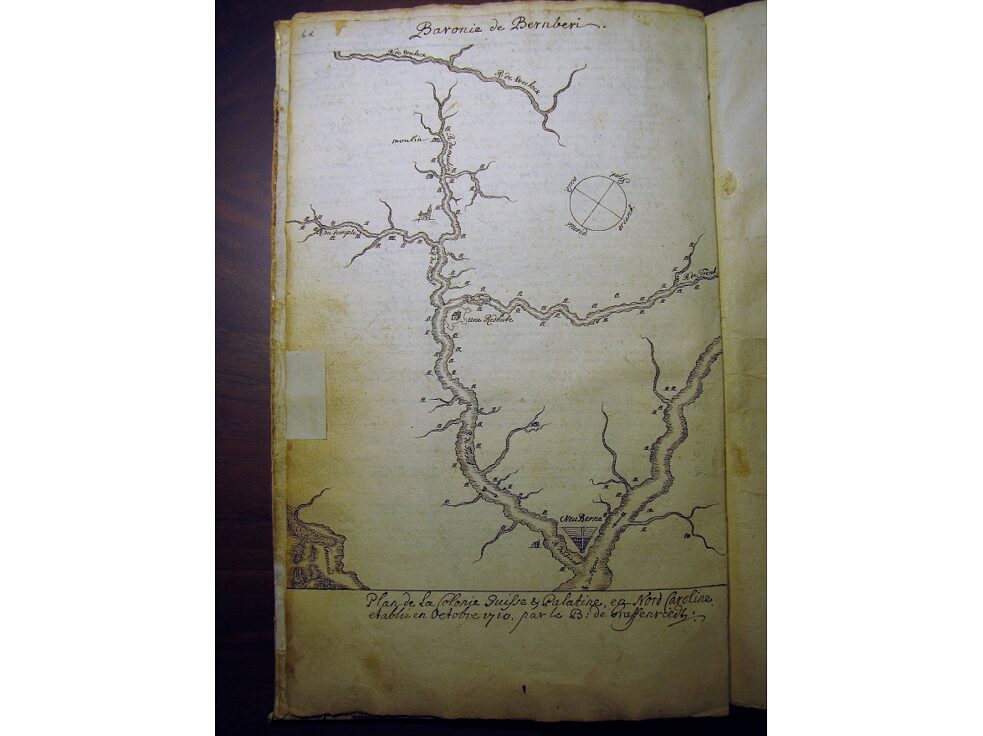

The richness of those findings led to the development of a narrative unfolding though different key processes: Swiss people led projects of colonisation in places such as the City of New Bern (in North Carolina, USA), well documented in travel books. They collected and accumulated goods, as attested by the multiple objects that were brought back to Switzerland. And they strongly aimed for profit, through the appropriation of non-European techniques but also the exploitation of human beings and the trade of enslaved people.

Exhibition view of the “Exotic?” exhibition

| © Lionel Henriot

The richness of those findings led to the development of a narrative unfolding though different key processes: Swiss people led projects of colonisation in places such as the City of New Bern (in North Carolina, USA), well documented in travel books. They collected and accumulated goods, as attested by the multiple objects that were brought back to Switzerland. And they strongly aimed for profit, through the appropriation of non-European techniques but also the exploitation of human beings and the trade of enslaved people. Christoph von Graffenried, Map of New Bern, 1704

| © Burgerbibliothek Bern

Christoph von Graffenried, Map of New Bern, 1704

| © Burgerbibliothek Bern

Material Modification of an Artifact

Exhibitions often generate conservation. One of the most interesting exhibited objects in the Exotic? exhibition is a folding screen that has been restored for the occasion. It was made in Japan and bought in China by a Swiss merchant, Charles-Constant de Rebecque. It mixes different temporalities (18th and 19th centuries elements), diverse origins (Japan and Europe for the lower parts) and distinct techniques (paper, silk, wood, lacquer imitation, ink, and painting). Such an object materialises the trajectory of goods and people across continents and time: it shows the complex identities of things and humans at this period of intense globalisation. Unrecorded artist(s), detail of a standing four-planel screen, 18th and 19th century

| © Musée historique de Lausanne

Another piece of interest is Nââkweta, a symbolic object from New Caledonia probably taken during the 18th century by Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux and donated to the cantonal museum of Lausanne by Benjamin Delessert. During the preparation of our exhibition, the activist and poet Denis Pourawa was invited by Claire Brizon to visit Nââkweta in storage and took it into his hands.

Unrecorded artist(s), detail of a standing four-planel screen, 18th and 19th century

| © Musée historique de Lausanne

Another piece of interest is Nââkweta, a symbolic object from New Caledonia probably taken during the 18th century by Antoine Bruni d’Entrecasteaux and donated to the cantonal museum of Lausanne by Benjamin Delessert. During the preparation of our exhibition, the activist and poet Denis Pourawa was invited by Claire Brizon to visit Nââkweta in storage and took it into his hands. Unrecorded artist(s), Nââkweta, 18th century

| © Nadine Jacquet

He did it without gloves and decided to attach a thread of his own scarf to the object. From his perspective, the gesture is a way to recognise Nââkweta as belonging to his cultural tradition and whose history has been transmitted to him orally. From the perspective of a museum conservator, however, one could wonder: Did this gesture compromise the stability of Nââkweta? Did the poet unwillingly destabilise the artefact? For Pourawa, this is clearly not the case (nor the point). The little trace he let on the object respectfully materialises the encounter between an artist and an object coming from the same region, attesting to the living connection between them. At the same time, seen from a purely conservative point of view, his intervention entails the moderate risk to impact the physical integrity of the historical artefact.

Unrecorded artist(s), Nââkweta, 18th century

| © Nadine Jacquet

He did it without gloves and decided to attach a thread of his own scarf to the object. From his perspective, the gesture is a way to recognise Nââkweta as belonging to his cultural tradition and whose history has been transmitted to him orally. From the perspective of a museum conservator, however, one could wonder: Did this gesture compromise the stability of Nââkweta? Did the poet unwillingly destabilise the artefact? For Pourawa, this is clearly not the case (nor the point). The little trace he let on the object respectfully materialises the encounter between an artist and an object coming from the same region, attesting to the living connection between them. At the same time, seen from a purely conservative point of view, his intervention entails the moderate risk to impact the physical integrity of the historical artefact.Thus, the example of Nââkweta shows an interesting case where the physical encounter between a human and an object can be read as a symbolic form of reparation in a context of colonial violence, while being at the same time a material modification comprising the risk of a potential degradation.

Who Needs Conservation?

Today, artists, conservators, curators, and academics are questioning the role of the museum in a postcolonial world. While exhibition spaces and displays have been widely criticised, studying conservation processes remains an innovative way to examine the ecology of care promoted by the museum. Conservation can be broadly defined as a science that aims to preserve and maintain the physical integrity of an artwork, sometimes in order to exhibit it. If we consider conservation as a Western science based on Euro-centered conceptions of time, materiality, and authenticity, conservation can also encompass a form of violence. Who preserves and who destroys? Can the museum continue to maintain the stability of the goods under its care, from an ecological, economical, and logistical standpoint?For instance, for the Zuni scholar Edmund J. Ladd, the typical standards of conservation are in fact problematic. According to him, his community should be responsible of taking care of the ceremonial goods. Furthermore, objects should be allowed to breathe and eat to survive. The conditions prevailing in most museum storages are in fact not appropriate to maintain the objects of collections alive.

Accordingly, conservators are beginning to rethink their practices, aiming for more sustainable and ethical interventions. Different projects, often led by conservators, are exploring, for instance, what a decolonised conservation could be. This movement of decolonisation by and through conservation typically includes consultations with so-called “source-communities,” - the people who fabricated the goods and their descendants. However, unfortunately, conservation and preservation are often arguments held against the possibility of restitution. Until today, the fragility of certain objects is one of the reasons argued against restitution demands.

An Expanded Understanding of Conservation

In a recent book (2020), Bonaventure Soh Bejeng Ndikung has discussed the notion of “care” and its well-intentioned, yet potentially damaging implications. He focuses on healthcare, the police, humanitarian international organisations, and curating. He suggests that many institutions in charge of “caring” for people or artworks are not devoid of political and sometimes unseen racists biases. His critics can also inform our approach of conservation. Who cares? Who decides what conservation is? Would it be possible to expand the definition of conservation so much so as to admit practices that could lead, ultimately, to the destruction of things? The artist Kader Attia has been questioning the politics of repair for more than a decade. Attia shows different modifications made on buildings, people, and objects. In his work, alternative ways of caring can help to pursue living, embracing the cracks and scars. Another definition of conservation can emerge from these perspectives.After the closure of the Exotic? show, Nââkweta went back to storage. To my knowledge, the thread is still there with it. The gesture performed in storage by Pourawa is a simple gesture that should not excessively be romanticised or interpreted. It is a thread of contemporary cotton attached to an object dating from the early 18th century. Nevertheless, the choice of keeping this intervention attests to an extended comprehension of conservation, where meaningful modifications are preserved, even if they don’t always align with conventional museum standards. In my view, it is showing a healthy tendency from museum professionals to acknowledge and welcome the vulnerability and fragility of material culture (and humans).