Digital Zine Meta(Return) Mor(Forgiveness) Phosis

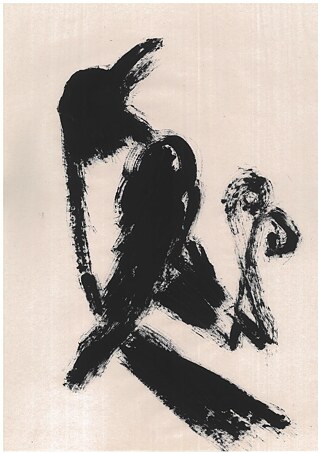

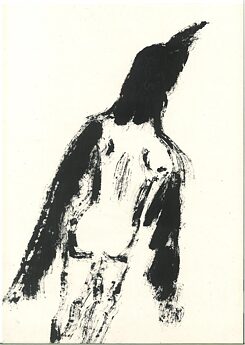

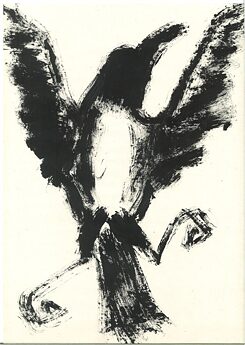

Can the arts give us comfort in difficult times? Haim Sokol draws people as birds, coming to terms with his turmoil as an artist from Russia.

I was recently asked if art is needed now, and if so, why.“Now” is such a euphemism to replace the word “war”. And the word “war” in turn allows us not to use words such as “death”, “bombing”, “occupation”, “looting”, “rape” and many other terrible and disgusting things.

I said something long in response. But I don’t think I said the most important thing.

Didn’t say that art is needed always and everywhere as a form of expression of dissent. That art is needed not only for denunciation or entertainment, but also for witnessing, and consolation, and deliverance. And now all the more so. Especially there, where war has come to. But also where war comes from.

I didn’t say that people lack empathy because they lack imagination. Because many people simply can’t imagine themselves in the other person’s shoes. And for that, too, you need art. And now even more so.

And also art must now redefine itself. Re-formulate its boundaries, its forms, its tasks. Perhaps this is why I think that now more than ever, poetry becomes the most important of all the arts. Because poetry is a way of redefining language, a place where language sheds its skin, transforms, mutates. It becomes something else while remaining itself. But weak, confused, unsure voices, polylingual, quirky, feminine are important and needed here. It is necessary to return to accent, stuttering, burring, lisping. Make the mother tongue a foreign language and vice versa.

This is all relevant to me because I am leaving – going back to Israel. Making my mother tongue a foreign language – for me it is not a figure of speech, but a reality taking on flesh. The decolonisation of language in my case means literally moving my own body from one language environment to another. Actually, this is the fate of many “now”. But Hebrew is no stranger to me either. And moving to Israel means re-colonisation for me. And there the words “war”, “death”, “fleeing”, “occupation” will not become more distant, more abstract. They will simply be pronounced in a different language and will take on additional meanings. In this context, I think a lot about what the homeland is, about fleeing and migration, death, resentment and the possibility of redemption, about violence and trauma. About transformation and mutation.

However, I always think about it.

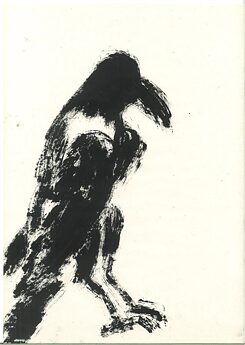

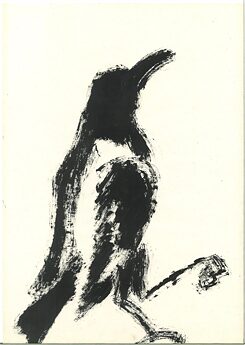

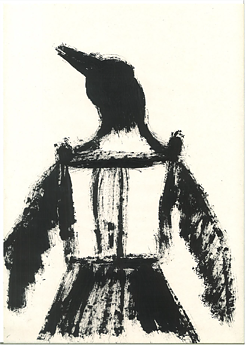

If you want to understand why I have people turning into birds, watch migrants squatting. Or how children play in the playground. When people are grabbed at rallies and carried by the hands, by the feet to the paddy wagons – they resemble birds.

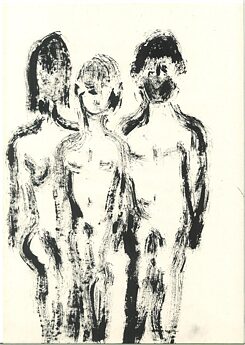

Look at pictures of people in extreme stages of emaciation – the prisoners of Auschwitz, for example, or starving Yemeni children. With their thin bones, their swollen chests, they look like birds without feathers.

I’m thinking about transmutations. When people turn into birds and animals. Women into men, men into women. The dead turn into gutters. Or into things. Or vice versa. Or simultaneously.

Does a chair, a man’s coat or a sock change its properties if you paint them pink? Do some cultural skills acquired through migration, such as language, become part of our body, DNA, which is inherited? So migration is a kind of mutation?

Transformation?

Is transformation a form of salvation? Or a form of resistance?

In his “Doctrine of the Similar”, Walter Benjamin talks about the important role of the mimetic faculty in the formation of language. Similarity – not as an existing resemblance, but as a correlation of the self with the object, a likeness (a time-drawn action), becoming it through imitation, which, according to Benjamin, took place in the ancient proto-practices of reading – astrology, divination by innards, ornament, dance. But the same can be said of drawing. Benjamin calls handwriting “an archive of insensible likenesses”, because in writing as a bodily practice (like dance) the unconscious manifests itself and thus the totality of likenesses which our generic memory retains, but which are hidden from us by semiotic meanings. If this is so, then graphics, which also derives from ’graphia’, i.e. writing, can also be considered an archive of similarities. And then my birds, superimposed on the ornaments of old Soviet carpets or cheap cotton mattresses on which migrants sleep, line up like ancient runes or hieroglyphs in special constellations and tell stories that we do not remember, but know.

Sometimes I think that even if my parents hadn’t told me anything about the war, even if I hadn’t read books or watched films, I would know everything. Because I know more than I see and hear, I know more than is written in books. I know more than I know. But what kind of knowledge is that? In scientific literature, it’s called post-memory. It’s a strange mixture of what you know about the past, what you understand and think about it, and how you relate to the past and how you feel about it. Simply put, it’s a memory of remembering. My experience blends with someone else’s in my memory, in my imagination, in my actions. It means I am somehow living someone else’s life, sharing someone else's destiny. But it also means that someone else or another, or others from there, from the past, get their second chance in me. In a certain sense, I become them and they become me. Hence the question: when I paint, who moves my hand? And above all, am I living someone's death at this moment or am I freeing (myself) from unbearable memories?

Memory is the sensory traces that some events or people leave in our minds. To keep these traces alive, people use various mnemonic practices, such as visiting graves, feast days, etc., or objects, such as photographs. But even with these rituals, monuments, archives, you have to keep telling what they are about, what for and why. Now imagine that there is no trace of someone or something, no monument, no photograph. And this or that someone was murdered. By whom? We don’t remember either. Or not murdered, but just were slaves or refugees. That’s what imagination is for.

It takes a great deal of imagination to break through the veil of truths that are indoctrinated and were indoctrinated into our minds. To think radically about the past means to renounce (at least temporarily) one’s own identity, biography, if you like, even one’s own reflection in the mirror – everything that shapes us as individuals – and to imagine oneself as someone else.

Homeland

This is some kind of switch.

Some strange euphemism

Denoting the totality of what

Did Indians in pre-Columbian America

Have their homeland

Or the French peasants

Before the Great Revolution

Or the serfs of the Russian peasantry

What is it

Home field wood

And does the tree have a homeland

Did Heidegger think

That his oak tree would grow to such dimensions

Probably thought so after all

Did he want it

Someone is dying for their homeland

On the battlefield

And in the gas chamber

They also die for their homeland

And if someone dies for their homeland

So someone is killing for it

In the Torah homeland

Is something to walk away from

Lech Lecha

Leave always

Forever

In the extended future

Out of your land

This is a testament to the dead

From their homeland

This is a testament to the living

From their father’s house

This is a precept to all concerned

Earth

Is the grave

Homeland

Is the uterus

Fatherland

Is the sperm

If so

Where the homeland is

Of unborn children

Of raped and murdered women

Where is my homeland

I am a homeless cosmopolitan

Walking on the fine hair of the line

From one homeland

To the other

Trying not to look down

The project “Dark Times, Bright Nights” (orig.: “Dunkle Zeiten, Helle Nächte”) by the Goethe-Institut in cooperation with the magazine dekoder invites authors and film and media professionals in Russia and in exile to document and reflect on the new everyday life since 24.2.2022. Further contributions can be found in the dossier on dekoder.

0 Comments