European Green Capital

Green … Greener … Lisbon?

The European Commission awards the title of “European Green Capital”, established in 2010, to a different city every year. This year’s title goes to Lisbon, in recognition of the Portuguese capital’s recent efforts to expand and improve public transport, reduce water and energy consumption, and green the urban environment. But is that all that is needed to be Europe’s Green Capital?

By Tilo Wagner

The city has changed radically since April 2020: no more traffic jams, no more ships docking at the newly built cruise terminal, and only 1% of the previous volume of air traffic at the local airport. In the wake of the coronavirus pandemic, air pollution in Lisbon is down 80 per cent – a drastic reduction in emissions that would thrill environmentalists and residents if it weren’t the upshot of an unprecedented shutdown to stop the spread of Covid-19, a respiratory infection with incalculable economic and social consequences for Lisbon, for Portugal and for the whole world.

Fewer Cars, Better Air

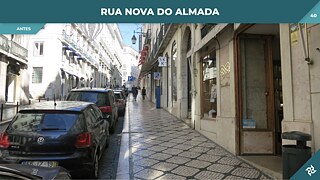

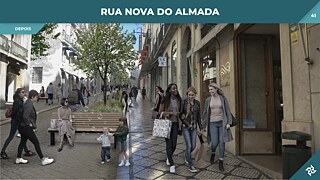

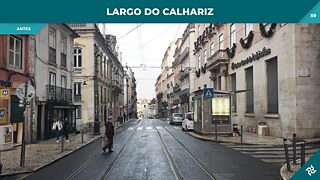

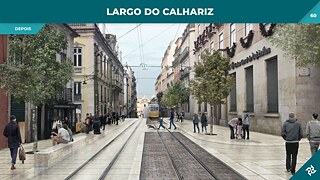

“These are, of course, extraordinary times,” says Francisco Ferreira, president of the environmental NGO Zero. “Still, we’ve got to seize this opportunity. When the economy gets going again, we should take immediate action to reduce traffic in Lisbon in the long term.” The Lisbon authorities were actually planning to ban diesel and petrol vehicles from part of the large Avenida da Liberdade boulevard, and from the narrow lanes of the old Baixa and Chiado neighbourhoods in the lower part of the city centre, starting in June (40,000 cars were counted in the city’s historic centre the day before the coronavirus crisis brought us the lockdown. This effort to massively reduce traffic in the old city is one of the flagship projects undergirding Lisbon’s claim to “European Green Capital”.Alternative Mobility

Lisbon’s overhaul is also the upshot of a general change of course at city hall. The austerity measures previously implemented over several years, partly under pressure from the troika of the EU, European Central Bank and International Monetary Fund during the Portuguese sovereign debt crisis from 2011 to 2014, had taken a heavy toll on local public transport: there wasn’t even enough money in the coffers for the upkeep of buses and metro trains, so the number of vehicles in service steadily dwindled and the number of passengers plummeted accordingly.But the introduction of a single and much cheaper monthly pass for the entire Lisbon metropolitan area turned the mass transit situation around in 2019. The city is investing in 100 new buses, including 30 electric vehicles. E-buses are already plying the first new routes. This is why Miguel Gaspar, City Councillor for Mobility, sees the “European Green Capital” title as a great green stimulus: “We know we were awarded the title chiefly in recognition of our efforts to date,” he concedes. “And yet this isn’t the end, but the beginning of the work that lies ahead. Over the next ten years, we aim to prove we can pull off a very rapid transformation.”

The city’s goal is to slash CO2 emissions by 55 per cent by 2035. To achieve that ambitious target, Lisbon’s urban planners are also banking on a hitherto neglected means of transport: Just a few years ago, there was hardly a single cycle path in town. Now a 200-km network is in the works.

More Trees, Better Water Management

Lisbon is going green more literally, too, by planting 100,000 new trees in the metropolitan area over the course of this year. Green corridors are to connect the huge Monsanto Park on the west side of the city with its centre. And the open-air sewage plant in Alcântara has been converted into a modern waterworks under a three-hectare garden, which recycles the wastewater so thoroughly that it can be used not only to clean the streets, water the city’s gardens and supply local industry, but even to brew Vira craft beer!Still a long way to go. Nevertheless, doubts persist as to whether Lisbon can really make the transition to a green city. Before the coronavirus crisis, roughly 370,000 cars entered the city each working day. And the Portuguese are still very attached to their cars, says David Vale, a mobility expert at the University of Lisbon: “People are fixated on cars in other European countries, too, but policymakers there have put their money on improving public transport. Not so in Portugal. Public transport here continued to decline and, instead of demanding politicians provide better service, the Portuguese bought cars. Which has also changed the passenger profile: thirty years ago, middle-class Portuguese would take the bus or metro too. Nowadays, public transport seems to be for the lower-income population. In this respect, Portugal resembles the USA more than other European countries.“

The Tourist Problem

Not only that, but the European Green Capital has yet to propose a sustainable solution to a pressing problem. Tourism has become the driving force of Greater Lisbon’s economy, accounting for 20.3 per cent of its economic output and over 200,000 jobs. Over 10 million people visited the nation’s capital last year – and poured cash into its coffers after the introduction of a €2 per-night tourist tax in January 2019. So last year’s city budget already anticipated direct revenue of €36.5 million. But this dependence on tourism also influences urban policy decisions.The city administration has supported two mammoth investment projects decried by environmentalists. In November 2017, a new cruise terminal was inaugurated below Alfama (the oldest part of Lisbon), increasing Lisbon’s total capacity from 500,000 to 800,000 cruise ship passengers per year. As a result, according to a study by the aforementioned NGO Zero, Portugal now has the sixth-highest levels of sulphur oxide emissions from cruise ships in Europe.

The expansion of Lisbon’s airport system is likewise controversial. The socialist government are hell-bent on building a new airport east of Lisbon in Montijo – along the edge of one of Europe’s largest bird sanctuaries. And they’re planning to expand Lisbon Airport, which lies a mere six kilometres north of the historic city centre. “The massive expansion of Lisbon’s airport system is not compatible with the whole idea of a European Green Capital,” points out environmentalist Ferreira. “This project jeopardizes the achievement of climate targets and will bring even more air pollution and noise in its wake.”

The pandemic has now hit tourism hard. So environmental and climate activists in Portugal are hoping that economic and environmental interests can be better reconciled as the nation gradually returns to normal. Lisbon, its nominal “environmental capital”, has a lot to gain from getting that balance just right.