Latin America

Right to Have Rights

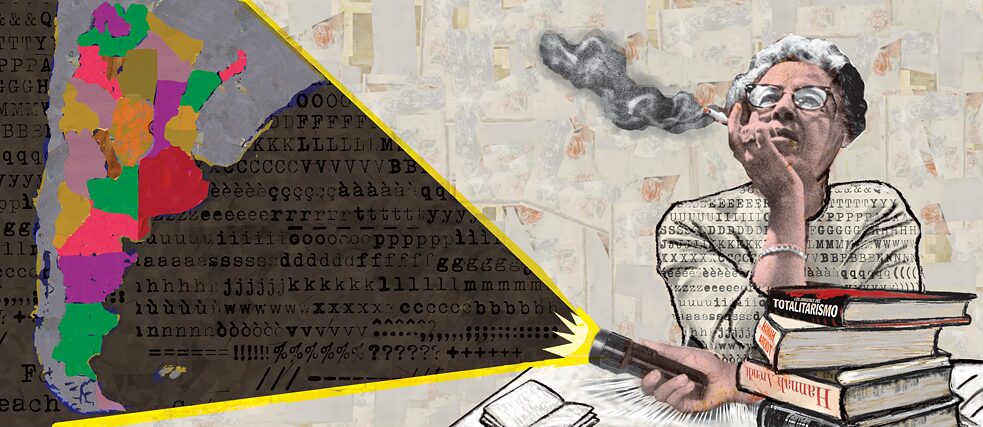

Argentine sociologist Claudia Bacci discusses the enduring relevance of Hannah Arendt's thinking in Latin America and asks who could be considered “stateless ” today.

By Silvina Friera

Ms Bacci, what impact has reading Hannah Arendt had in Latin America?

The most fruitful readings began in the 1980s. Those were connected to processes of redemocratization following the dictatorships and armed conflicts of the previous decades, but her works were circulating around the region well before—the first publications were in German, and there were also translations by editors and intellectuals connected to the left, to anti-Nazi German exiles and also German-Jewish exiles during the Second World War.

In Brazil, the figure of the jurist and diplomat, Celso Lafer, a former student of Arendt at Cornell University, was central. He recalls discussions from the 1970s and 80s with intellectuals such as Antonio Cándido, Hélio Jaguaribe and Francisco Weffort, who were connected to Brazilian social democracy and the left. In the case of Colombia, cultural critic and essayist Hernando Valencia Goelkel translated some of Arendt’s texts in the 1960s in Eco magazine, which aimed to bridge Latin American and German culture, with the support of the Inter-Nations Association. In an article from 2024, Ellen Spielmann, who studied Arendt’s reception in that country, highlights the figure of Valencia Goelkel for her role as an adviser to President Belisario Betancur in the 1980s, for having contributed to the first attempts at establishing peace talks with the Colombian leftist guerillas from an Arendtian republican viewpoint.

A piece I published in 2022 about reading Arendt in Argentina makes clear that her book Eichmann in Jerusalem elicited a varied reception, including heated discussions about it in magazines read by the Argentine-Jewish community in the 1950s and 60s, but there was also a sort of indifference to Arendt’s analysis of totalitarianism and a lack of understanding of her particular vindication of the political, considered to be elitist in the late 1960s.

Exile in Mexico and France during the military dictatorship in Argentina (1976-1983) gave rise to the first readings of her works among left-wing intellectuals. One important figure was the German-born Chilean political scientist, Norbert Lechner, who influenced those debates in the 1980s from an Arendtian perspective. Also relevant in the 1990s was Elizabeth Jelin’s work on citizenship and human rights; Horacio González reflections on the responsibility for the crimes of state terrorism; Héctor Schmucler’s centering of testimonies in the elaboration of social memory of that period, as well as Pilar Calveiro’s Arendtian reading of “concentrationary power.” The jurist Carlos Nino, an Arendt scholar, advised then President of Argentina, Raúl Alfonsín, on the definitions of the judgement of the Military Juntas, and Claudia Hilb proposed a critical reading about the relationship between violence and politics in the 1960s-70s.

What concepts can Arendt’s theories contribute to the ways in which state terrorism has been thought about in Latin American dictatorships?

The concepts that are most frequently referenced are the “banality of evil,” “totalitarian domination,” and “totalitarian terror” as well as her view on the role of bureaucracies in totalitarian contexts and the issue of personal and political responsibility in the face of violence. Eichmann in Jerusalem is the book which, as I understand, provided an outline for interpreting state terrorism and dictatorship in the region. In Argentina, Horacio González pointed out in 1989 that although Arendt was not a reference for understanding the revolutionary violence prior to the dictatorship, the philosopher was considered to be “almost Argentine” for her thinking on the social effects of dictatorship with her critique of “due obedience”. Schmucler also drew deeply on Arendt’s thinking to ethically judge the continuing horror when facing the disappearance of bodies of the people who had been kidnapped by state terrorism.

From Brazil, Celso Lafer and Cláudia Perrone-Moisés considered the importance of transitional justice and reiterated Arendt’s perspective on the difficulty in punishing crimes committed by Latin American dictatorships within the existing legal framework. For instance, they turned to this author’s perspective on the “unforgiveable” nature in terms of justice policies, to consider other relationships between justice, memory and truth in the presence of these crimes. In this sense, I would say that what Arendt is saying is also about us here in Latin America.

“To be stateless means that you are deprived of the right to have rights,” Arendt wrote. Who are the stateless people of the 21st century?

I think that the power of this idea today, encapsulated in Arendt’s idea of the “right to have rights,” exceeds the specific significance that she had attributed to it in her work The Origins of Totalitarianism, where it was a result of the decline of the Nation-State and imperial expansion of the late 19th and early 20th centuries. There, the problem of denying citizenship, in other words, rights guaranteed by the Nation-State, produced flows of refugees and displaced persons in Central Europe and a new category of subjects-without-rights, the stateless.

The most recent geopolitical, socioeconomic and environmental global transformations provide a certain continuity to the processes of population displacement, exile and forced migration, which involves depriving people of the conditions for its basic exercise without expressly resorting to the expulsion of citizenship status. Although international declarations of Human Rights and the Rights to Refuge and Protection exist in instances such as war and other types of armed conflicts, these institutions and the nation-states themselves seem powerless, or even reluctant, to recognize the “right to have rights,” whether it be in Europe, Africa, the Middle East or Latin America.

In our region, the seriousness of current economic and social expulsion and of political and (para)state violence is pushing citizens to seek a dignified life even if it means losing their rights as citizens of a State. Without being strictly “stateless,” they suffer all the effects of losing the “right to have rights” in the contemporary world. The refugee and immigration crises, the persecution of advocates for indigenous lands and of activists against extractivism that have been sweeping Latin America have been going on for decades. So, the demand for the “right to have rights” persists today.