Chen Wei

How Loneliness Favours Totalitarian Systems

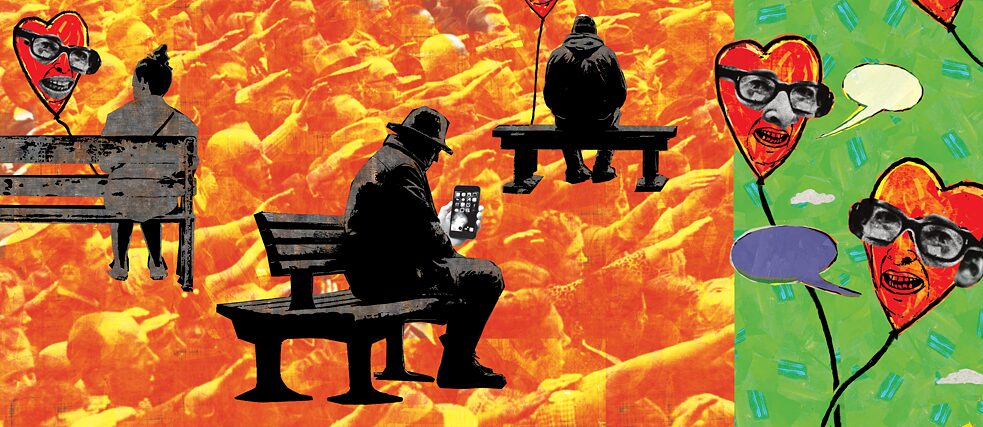

How does loneliness affect modern man – and why is it a breeding ground for totalitarian rule? Chinese philosopher Chen Wei analyses Hannah Arendt's thinking and shows how political participation can counteract withdrawal into private life.

It is a fact that many prefer to ignore: the 20th century was defined by totalitarianism – and the same can be said of the 21st century. The end of the Cold War in the early 1990s did not lay totalitarianism to rest. Despite Fukuyama’s proclamation, history did not reach its conclusion; its wheel continues to turn. Yet it is neither moving back towards the wars of religion feared by Mark Lilla, nor towards Huntington’s Clash of Civilisations – nor even in the direction of the identity politics of the contemporary West. Instead, history is reviving the classic struggle between liberal democracy and totalitarian dictatorship. Once more, an invisible Iron Curtain is descending, dividing East and West anew. Far from securing humanity the freedom and liberation Francis Bacon once envisioned, the advancement of science and technology has only intensified this conflict.

One cannot help but ask why the painful lessons of the three great wars of the last century – including two “hot” and one “cold” – failed to bring about humanity’s moral progress. Why does totalitarianism behave like a centipede, already considered dead yet still crawling forwards? To understand this, it is worth revisiting the anti-totalitarian theorist Hannah Arendt.

Arendt's approach

Hannah Arendt (1906–1975) was born into an assimilated German-Jewish family. To escape Nazi persecution, she emigrated to the United States, where she became a prominent figure in the postwar intellectual elite. Her major works include The Origins of Totalitarianism, The Human Condition, On Revolution and The Life of the Mind. Through her writing, concepts such as totalitarianism and revolution gained distinct significance and became established tools of theoretical analysis. In the history of political thought and within contemporary Western political discourse, Arendt thus occupies a singular position.According to Arendt, every political order is governed by its own principles, rooted in or reflecting specific human experiences of existence. Consequently, neither an institutional nor an action-based understanding of politics fully captures the essence of a given form of government. Regarding the new form of government in the 20th century – totalitarianism – she argues that it corresponds uniquely to the conditions of modern human life: loneliness and superfluousness, alienation from a shared world and the breakdown of traditional bonds. Above all, Arendt considers loneliness to be a fundamental existential experience of modern man. In ancient societies, by contrast, it was considered a marginal phenomenon, as Cicero suggested in De senectute. Absolute loneliness and despair can, at times, be more devastating than death. One can envision the lost, isolated individual seeking solace in the arms of totalitarianism, like a thirsty person trying to quench their thirst with poison. Yet the establishment of totalitarian rule does not alleviate loneliness; rather, it nurtures and intensifies it, ultimately enabling control over the individual and a radical denial of humanity.

Loneliness and Modernity

From Arendt’s perspective, the loneliness of modern man can be understood in at least two ways:First, it is a consequence of the secular age. Loneliness initially manifests as an inner emptiness and lack of grounding. Without transcendence, human beings are cast into the world. Weber describes Calvinists engaged in solitary ascetic self-examination, whose doctrine of predestination intensified uncertainty about one’s fate in this life and salvation in the next. In the era in which Nietzsche proclaimed the death of God, humans were conceived as materialistic, soulless atoms – bodies with energy but deformed without spiritual life. Their loneliness stems precisely from this inner closure and the collapse, indeed the disappearance, of their spiritual world. Neither God nor the light of reason can illuminate their existence. The logical outcome is Nietzsche’s Übermensch, guided solely by the will to power. In such a world, only the law of attraction and repulsion between atoms applies. Philosophically, this perspective found expression in the existentialism that emerged in the 20th century. Arendt, who studied under the existential philosophers Karl Jaspers and Martin Heidegger, recognised the lonely condition of modern man. Through the lens of existentialism, she reflected on totalitarian rule at a deeper level than the experience of loneliness in the modern world, and critiqued it accordingly.

Second, the loneliness of modern man is a social consequence of industrialisation and modernisation. For Arendt, it was the chronic illness of the age. Modernisation did not come freely to humanity; one of its costs was the destruction of public connections. With secularisation, the Church largely withdrew from daily life. Simultaneously, liberation from feudal serfdom in the Middle Ages and the collapse of small-scale peasant economies in the East led to the disintegration of traditional village communities.

Cities gave rise to industrial civilisation, yet they failed to forge new bonds of solidarity. A work ethic governed by economic rationality left little room for human warmth. In place of the classical citoyen emerged the bourgeois; social cohesion and personal responsibility towards the public sphere vanished. The modern petty-bourgeois individual could sip their afternoon tea amid the chaos of war, while corpses piled up next to them.

Such lost and powerless individuals, who have forfeited all civic cohesion, form the most fertile ground for totalitarianism: the modern masses. Despite their size, these masses remain profoundly lonely. In crowds and fanatical shouting, they seek relief and attempt to give their lives meaning. Yet loneliness fuels the quarrelsome tendencies of the individual; magnified within the masses, aggression and destructive impulses gain social legitimacy and are, in effect, “excused”.

Even Aristotle warned that a person withdrawn from the community ceases to be fully human. Similarly, Arendt – drawing on Martin Luther’s commentary on the biblical passage “it is not good for the man to be alone” – emphasised that a normal human life is impossible in solitude.

Mind vs. terror

The ideology of struggle became the favoured philosophy of the modern masses. Totalitarianism is organised collective crime; its essence rooted in total terror. It offers the isolated individual the illusion of accomplishing great deeds and making history – indeed, it even promises paradise on earth. Yet its triumph leaves behind a “lonely desert without neighbours”: the total domination and destruction of both public and private life.In a sense, Arendt’s later engagement with The Life of the Mind can also be read as a critique of the individual’s experience of loneliness. She examines the political dimension of the individual’s inner life, identifying three fundamental activities of the mind: thinking, judging and willing.

Although the development of the life of the mind requires withdrawal from the world, the individual does not lose connection to it or to their public dimension. In the act of thinking, when the self reflects upon and encounters the “Self”, the individual ceases to be inwardly closed. Thought opens a space for reflection and raises fundamental questions about the meaning of life. This “Self” is always oriented towards the public sphere, reminding and cautioning us in this regard.

In the act of judging, the individual engages with a multitude of potential others in an imaginary, evaluative dialogue about a shared object. From this emerges a public judgement that, while not universal, retains its validity and effectiveness. This individual capacity to judge is closely tied to what Arendt calls “common sense”, a kind of seventh sense that transcends mere seeing and hearing.

In willing, the individual must also consider the future, deciding whether or not to act. In doing so, they must also acknowledge the consequences and responsibilities of their actions for the community. By contrast, the isolated individual possesses no life of the mind at all.

Western self-reflection

Arendt’s reflections, as outlined above, are deeply rooted in a European context. The lonely existence of the individual, their entanglement with the modern state and the experience of totalitarian regimes in the 20th century are phenomena characteristic of the European continent. The Anglo-Saxon world, by contrast, largely escaped this trap.In societies of the eastern hemisphere, which modernised later, elements of 19th-century European nationalism were adopted and transformed into an overly assertive “anti-Western stance” to uphold national prestige and justify authoritarianism and modern dictatorships. Western civilisation, however, had already embarked on a profound process of self-reflection.

Hannah Arendt stands out as a leading figure in this historical reckoning. Her reflections are closely linked to her own experiences as a Jewish refugee: after years of “statelessness”, she forged a new life in the United States, which allowed her to participate actively within a different tradition. Through direct experience of political participation and exposure to various civil rights movements in the New World, Arendt discovered ways to confront the loneliness of modern humanity and resist the allure of totalitarianism.

No freedom without civil society

Theoretically, Ahrendt drew on the classical republican tradition to address the deficiencies of liberalism: its neglect of the political, its lack of collective responsibility and its tendency to retreat into the private realm. She provides the theoretical tools to confront totalitarian movements, whether from the left or the right – and offers the intellectual resources to rebuild a shared world and cultivate a vision of the future.For Arendt, civic action is fundamental; for her, a public, political life is indispensable. Recognition of plurality underscores the impossibility of any reductionist understanding of humanity. To regard humans as humans is to recognise them as individuals – not atomistic beings detached from the world, but receptive individuals living among equals, each with their own desires and hopes. Only by overcoming the isolation of modern man can we find ways to render totalitarian rule impossible.

Hannah Arendt highlights how liberalism, in its struggle to resist totalitarianism, often acts indecisively, pragmatically and opportunistically. History has repeatedly shown that the appeasement tendencies of liberal democracies only allow totalitarianism to advance further. England and the United States remained largely immune to the “virus” of totalitarianism because, beyond mere liberalism, they retained their republican political roots and traditions and a respect for the political legacy of ancient Greece (polis) and Rome (res publica). Revisiting the political development of these ancient civilisations, Arendt emphasises the necessity and urgency of reviving the political dimension of human existence. This entails an effective interplay between the individual and the shared world, that enables the pursuit of freedom, morality and justice even without reference to God. Calculated opportunism or brute force, she argues, cannot fulfil this mission.