Actually, plastic is a great thing. It’s a wonderfully practical material: lightweight, durable to the point of being indestructible, water-resistant, infinitely moldable, and even democratic. Because it’s inexpensive to produce, it made many products accessible to the masses. After World War II, plastic became the building blocks of the future: everyday items, clothing, medical equipment, car parts, electrical appliances, solar panels, space exploration, food packaging. Plastic saves lives and drives technological progress, insulates houses, and makes food transportable and longer-lasting. Plastic is everything; without plastic, nothing works.

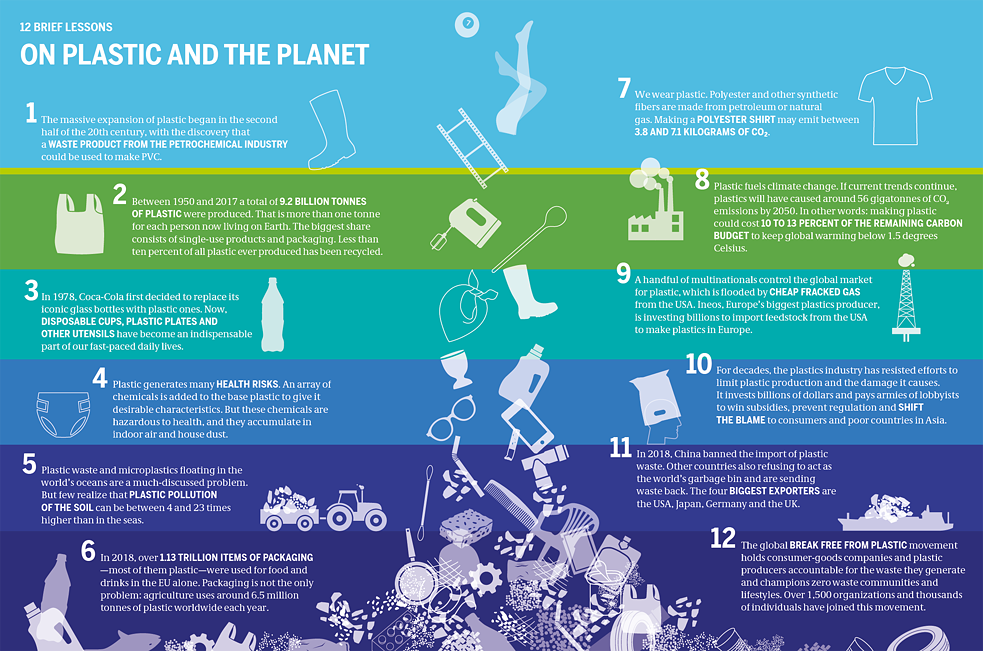

Since the 1950s, plastic production has grown exponentially. In the years from 2003 to 2016 alone, as much plastic was produced as in the previous 60 years. Today, humanity produces hundreds of millions of tons of plastic every year. We are living in the age of plastic.The problem is that, when it has fulfilled its purpose, we don’t know where to put all the plastic. Plastic has long surpassed humanity’s capacity to manage it. As is often the case with a great invention that also allows for profit-making, not enough thought was given to the medium- and long-term consequences. Plastic waste is one of the biggest problems our planet is currently facing.

And there’s a lot of it, especially because many plastics are designed for single-use. The numbers are staggering: Humanity produces over 200 million tons of plastic waste each year. To put that into perspective, the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) provided a conversion in a report from 2021: It’s roughly equivalent to 523 trillion plastic straws, which, if laid end to end, could wrap around the Earth about 2.8 million times. In short: It’s a lot!

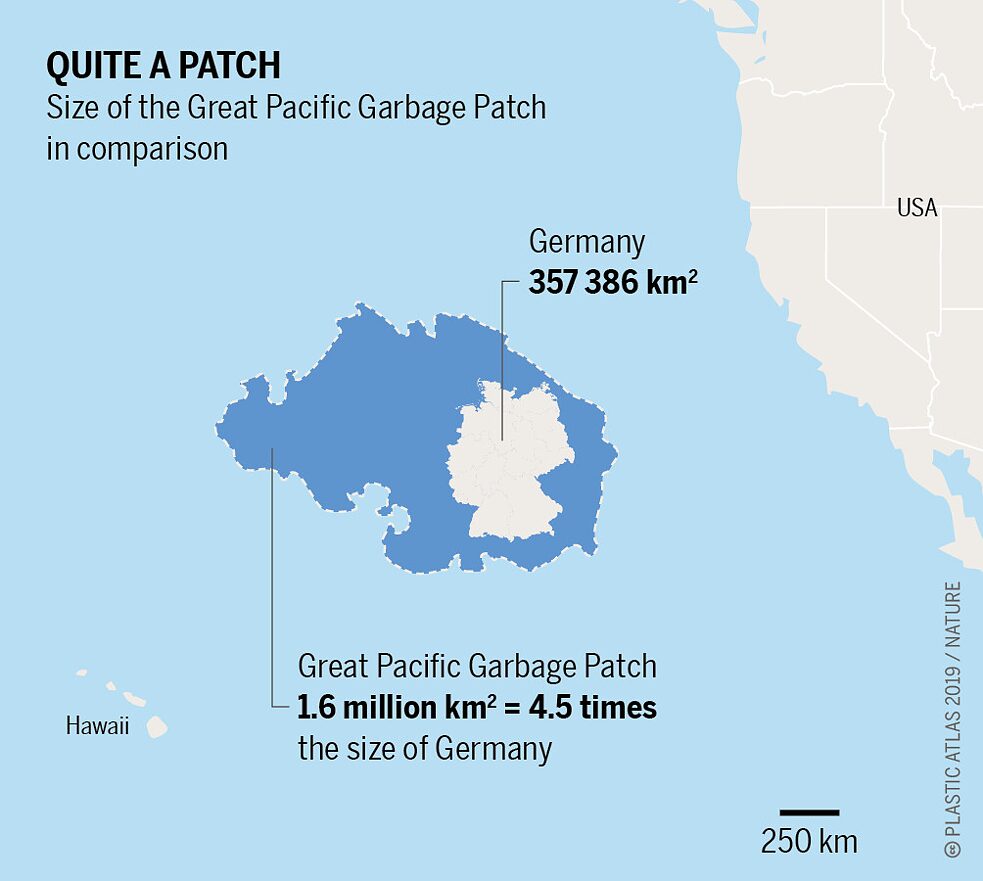

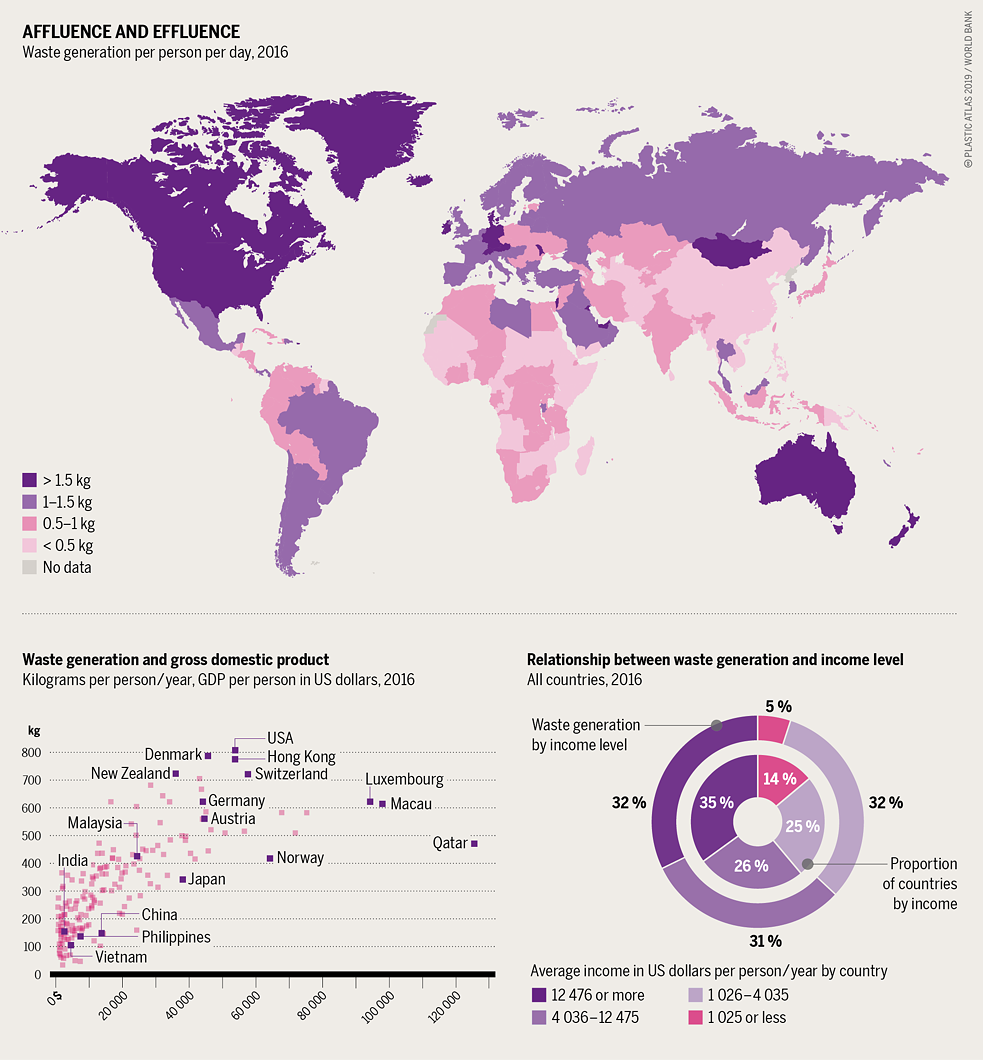

However, production is only the first, smaller part of the problem. The much larger issue is that the majority of countries have woefully inadequate collection and disposal systems for such a massive amount of waste. Over 40 percent of global plastic waste is improperly disposed of, leading to a significant amount ending up in the environment, particularly in the oceans. One of the most striking examples is the Great Pacific Garbage Patch: the world’s largest garbage vortex floating between Hawaii and California, which is as big as Germany, France, Spain, and Portugal combined. In addition to plastic waste from shipping and fishing industries, the main source of plastic pollution comes from land, carried by rivers. To put it in numbers, 11 million tons of plastic waste enter our oceans every year, which is nearly 14,000 plastic bottles per second! Even the vastness of the oceans cannot absorb such quantities. Moreover, once the plastic is in the ocean, it is practically impossible to remove.

The mass die-off of animals threatens not only ecosystems but also the fishing and tourism industries, as well as the food source for many people. An even bigger problem is a characteristic that once made plastic such a sought-after material for the future: its long lifespan. It can take several hundred to thousands of years for it to completely decompose. Plastic breaks down slowly, forming smaller and smaller particles known as microplastics. These tiny, solid, water-insoluble particles are everywhere — in every square kilometer of the oceans, in the Arctic, in the deep sea, in lakes and rivers. And they also enter the human body through water and food. How exactly they affect our health is not yet sufficiently researched. It’s certainly not good, as plastics contain plasticizers and other chemicals.

So, the problem is already gigantic. And it has long since become autonomous. Even if we were to stop the pollution immediately, the amount of microplastics would still more than double in the next three decades. Producing less plastic would be logical. Instead, the plastic industry alone has invested 180 billion US dollars in new factories since 2010. For even more plastic for the world. Or to put it differently: The catastrophe is already on the horizon, and humanity is accelerating it even further, waving flags in the wind. Hurray, we are doomed.

In essence, plastic pollution can be explained even more succinctly than global warming, highlighting the perverse extent to which the destruction of our planet has long gone. One doesn’t need to grasp the intricacies of the greenhouse effect to understand that the garbage heap we’re sitting on is already too large and still growing. And we have no idea where to put it.

What’s clear is that this isn’t just a problem for humans and nature, but it will also cost us an awful lot of money in the future. Plastic procurement is cheap and therefore still the preferred choice for many manufacturers, but, the bill that we all — countries, communities, families, and individuals — will have to pay in the end is significantly higher. While there aren’t official numbers, according to the WWF report, every euro that manufacturers invest in plastic production costs us at least ten times as much to offset the negative effects on the environment, society, and economy. On one side, there are costs for waste disposal (and mitigating improper waste disposal) and greenhouse gas emissions. On the other side, there are incalculable healthcare expenses and, especially, the damages that need to be addressed in ecosystems.

WWF has calculated that the lifecycle costs alone of the plastic produced in 2019 amount to an estimated 3.7 trillion US dollars. A gentle reminder - one trillion is 1000 billion. It becomes even more unimaginable when looking further into the future: by 2040, we would be at 7.1 trillion dollars. That’s 85 percent of the global health expenditures of 2018 and more than the gross domestic product of Germany, Canada, and Australia combined in 2019.

So, it’s going to be costly, and as for who ends up footing the bill, no country has come close to providing an adequate answer thus far. Even in places where one might think waste disposal is somewhat successful, a closer look reveals the reality: recycling is happening, but not enough. There are too many exceptions to bans. Or the problem is simply being shifted: For example, in 2020, Germany shipped 136,083 tons of plastic waste to Turkey, where it’s officially supposed to be recycled, but often ends up being illegally burned.

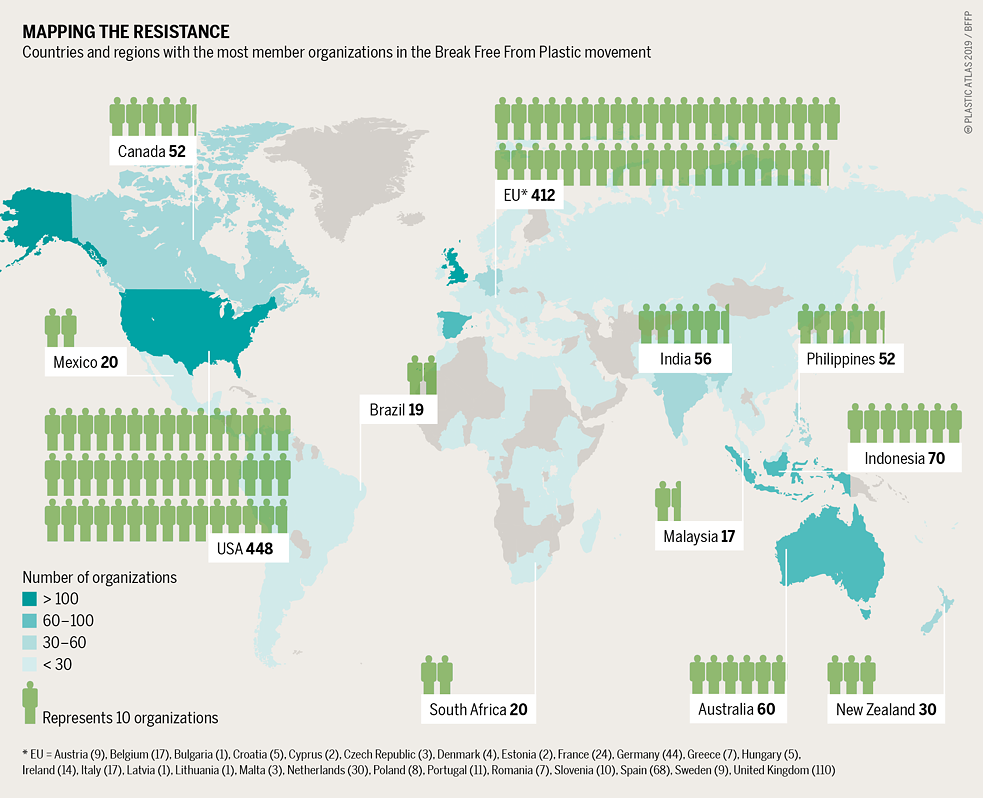

Plastic, much like climate issues, can’t be solved individually but rather requires global approaches and agreements. A comprehensive ban on single-use plastic products such as straws, takeaway cups, plastic bags, and Styrofoam containers, as decided by the EU in 2019, would be a good, albeit still small, step. A more meaningful solution would involve imposing fees on companies that produce or use plastic. These funds could be invested in collection and recycling systems (Germany and many European countries already have corresponding regulations — but only for packaging). Addressing our plastic problem is going to be a monumental task.

Annett Scheffel on the Plastic Age

Further Reading:

WWF: “Plastics: The Costs to Society, the Environment, and the Economy”PBS: The Plastic Problem

The Ocean Cleanup

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP): “Neglected: Environmental Justice Impacts of Marine Litter and Plastic Pollution”

Related Links

09/2023